Finding a door | Attorney Thomas Cox takes on mortgage giant GMAC and ignites a national foreclosure freeze

Attorney Thomas Cox returns to the Portland offices of Pine Tree Legal on a recent overcast November day with an envelope in his hand. He has just taken a short break from the daunting load of home foreclosure cases he’s handling for the legal services nonprofit to retrieve a piece of restricted mail from the post office. Inside the brown envelope, he finds a handwritten note from a Connecticut man who’d read about Cox’s pro bono foreclosure work in the New York Times. “Dear Attorney Thomas Cox,” the letter writer scrawled, “Your work is saving dozens of lives, possibly hundreds of lives — although it is too late for me. Keep up the good work.”

In place of a traditional closing, the man signed himself “Pre-‘Final Exit’,” referring to a 1992 book by Derek Humphrey, founder of the Hemlock Society, that details methods for suicide. The man included his full name and address, along with a postscript with the name and telephone number of his “executioner in absentia,” a local foreclosure lawyer.

Unnerved, Cox returns to his small office to locate help for the man before it’s too late. The letter is dated five days prior. With it, the man enclosed copies of two news articles, one about a study showing high rates of depression among homeowners facing foreclosure and another detailing the story of a Texas mayor who killed her daughter and then herself after suffering from financial troubles including foreclosure.

Cox sits straight up in his chair, the phone pressed to his ear. He reaches a local police department, but gets shuffled off to voicemail. He then manages to track down a Connecticut mental health clinic online and alerts the staff there to the man’s letter. Then he waits.

More than five hours later, at 8:15 p.m., one of the mental health worker calls. Accompanied by police, they found the man in his home, alive but resistant to help. The caller tells Cox the man had been involuntarily committed to a mental health facility.

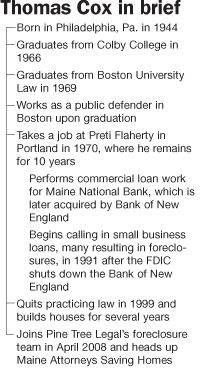

Unsettling as the incident was, it wasn’t altogether shocking to Cox. Now 66, he has battled depression for much of his adult life, and sunk into a serious episode 10 years ago after his work calling in business loans for a Maine bank left his conscience heavy and his marriage battered. Many of the small business owners he’d worked with had put up their houses as collateral, and he’d witnessed the devastating effect it had on their lives. “There I was foreclosing on these people’s homes,” Cox recalls. “These were people I knew.” The experience drove him away from practicing law for nearly a decade.

His professional history plays no small role in Cox’s motivation for the work he does today, as head of the Maine Attorneys Saving Homes project, which coordinates pro bono legal referrals for foreclosure cases. What started in April 2008 as a 10-hour-a-month volunteer gig and a way to dip his toes back into the legal profession has grown into a full-time unpaid job for Cox that has landed him in the national media and in the crosshairs of one of the country’s largest mortgage companies.

Cox is largely responsible for setting off the nationwide uproar over the mishandling of foreclosure cases by some of the nation’s most prominent lenders. By exposing the practices of a GMAC Mortgage Co. employee who matter-of-factly admitted to signing hundreds of foreclosure documents a day with little knowledge of what they actually said, Cox helped to trigger a foreclosure investigation by all 50 states’ attorneys general into the practices of mortgage lenders and servicers including Bank of America, JP Morgan and GMAC, which announced on Sept. 17 that it would temporarily stall foreclosure sales and evictions in 23 states, including Maine. GMAC services more than 20,000 mortgages in the state, and upwards of 1,000 have gone to foreclosure over the last four or five years.

For Cox, that announcement marked the most rewarding moment since he returned to practicing law. “We’d gotten them to pay attention in many, many cases in many, many states,” he says. Cox was able to crystallize the nature and scope of the problem like no one else before him, largely due to his experience working the other side of foreclosure cases, according to his friend and fellow foreclosure attorney at Pine Tree Legal, Chet Randall. “Tom was able to close any doors that remained open for creditors to explain away these issues.”

Digging in

The moment Cox first read an affidavit signed by GMAC employee Jeffrey Stephan, he knew something was off. First of all, Stephan was listed as a “limited signing officer,” which indicated to Cox right off the bat that “all he was was a paper signer.” Also, Stephan’s name was clearly inserted into a space left blank in the document, meaning the lawyer who prepared it hadn’t actually spoken to Stephan. Cox would soon discover more affidavits just like it. “The minute I saw them I knew they were bogus,” he says.

Dressed casually in a brown sweater and gray slacks, Cox props his foot on a computer tower in a sparsely decorated borrowed office at Pine Tree Legal as he describes the origins of the case that landed him in the national spotlight. That first affidavit involved a foreclosure case against a woman named Nicolle Bradbury who had fallen behind on payments for her modest $75,000 home in Denmark. Cox hadn’t planned to take her case initially, as his primary role was to refer cases out to other attorneys as pro bono work. But the program didn’t have any volunteers in Bradbury’s rural part of western Maine and a response on her behalf needed to be filed with the courts immediately. “I was trying to stay out of the fray,” Cox says, his blue eyes bright behind gold-framed glasses. “It didn’t work.”

Cox later won approval to depose Stephan, and traveled to Pennsylvania to meet with the 42-year-old GMAC employee. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, Stephan was articulate and seemed intelligent, Cox says. “He was totally candid and not seemingly embarrassed or concerned at all with what he was doing,” he says. Stephan acknowledged that when signing his name to an average of 400 foreclosure case affidavits per day, he checked only the balances due and the due date with no attempt to verify their accuracy. “When you receive a summary judgment affidavit to sign, do you read every paragraph of it?” Cox asked him, according to a transcript of the deposition. “No,” Stephan replies simply.

Cox had prepared to battle with Stephan for hours to drag such admissions out of him. “I didn’t have to fight with him. It just came out,” he says. Stephan had been deposed twice before, in Florida and New Jersey, but the other attorneys didn’t quite get to “the good stuff,” Cox says, and failed to either recognize or pursue the implications of his admissions beyond their individual cases.

In a court filing, Cox laid out what he had learned from the man now known as the “robo-signer,” a moniker Cox dislikes “because it tends to minimize the nature of the dishonest conduct of a person signing affidavits that contain serious lies and false statements. The legal term for such conduct is ‘perjury’ and that is what accurately describes these affidavits.

“When Stephan says in an affidavit that he has personal knowledge of the facts stated in his affidavits, he doesn’t. When he says that he has custody and control of the loan documents, he doesn’t … When he makes any other statement of fact, he has no idea if it is true,” he says.

Cox has been asked on more than one occasion if he thinks Stephan grasped the error of his ways. “I don’t know how he could not know,” Cox says, incredulous. The affidavits clearly state that the signer has personal knowledge of the documents’ accuracy, including attachments, of which there were sometimes four different versions, Cox says. “I can’t accept the guy didn’t know, but I didn’t ask him that, and I didn’t ask him that because I had gotten a lot of good information there and I didn’t want to risk having [Stephan and his lawyers] walk out saying I was going too far.”

GMAC’s lawyers soon did make the argument that Cox went too far. Aware that he’d found an opening in the case that could not only help Nicolle Bradbury but also undermine foreclosure proceedings against thousands more like her, Cox posted the deposition to an email listserv for the National Association of Consumer Advocates that was soon picked up by a Florida blog. Shortly thereafter, GMAC’s newly appointed local counsel at Portland’s Pierce Atwood accused Cox of malicious dissemination of the document for commercial gain, even though he was working pro bono, and sought financial sanctions against him. The firm also asked the court to force Cox to recover the deposition online and prevent him from sharing it or using it in future cases.

“Their first effort was the cover-up,” Cox says. “In 20 years I’ve never had another law firm come after me personally for sanctions like that. The words they used in their papers were offensive to me.” A Pierce Atwood attorney declined to comment on the case, though a GMAC spokeswoman told Mother Jones that “any attempts by Mr. Cox to characterize the pleadings in an inflammatory fashion are categorically disputed.”

District Court Judge Keith Powers didn’t buy the company’s argument, ruling that GMAC hadn’t shown “good cause” to shield the document. “That the testimony reveals corporate practices that GMAC finds embarrassing is not enough to justify issuance of a protective order,” he wrote.

The big picture

Nicolle Bradbury is now one of six Maine plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit against GMAC being tried by Cox and five other attorneys. In September, Judge Powers ruled that Jeffrey Stephan acted in “bad faith” in Bradbury’s case and reprimanded the mortgage company for continuing such practices even after a Florida court warned it four years ago about the very same signing procedures. GMAC was ordered to pay Cox about $25,000, what he would have been paid had he been charging Bradbury. Cox is now trying to settle Bradbury’s case, and a group of half a dozen benefactors who learned of her plight have stepped in with offers of money toward that end.

The fact that she defaulted on her home loan, however, is clear, and Bradbury and others in her position draw no sympathy from many who see Cox’s efforts as letting delinquent borrowers off the hook. “The underlying facts of default in the named plaintiff’s cases are not in dispute,” Jim Olecki, a spokesman for GMAC’s parent company, Ally Financial, said in a statement. “The average property is not foreclosed on until the mortgage is unpaid for 18 months and all other home preservation options have been exhausted. We will vigorously defend the allegations in the class-action lawsuit.” But Cox says he has yet to encounter a homeowner who intentionally let their payments lapse. “So many people say these people are deadbeats,” he says. “I absolutely reject that and bristle at that.”

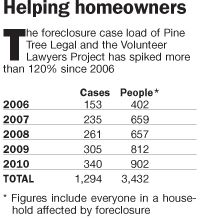

Of all of the homeowners in Maine facing foreclosure, 90% do so without representation, according to Pine Tree Legal. The legal services nonprofit, working with the Maine Volunteer Lawyers Project, meets only an estimated 6% of the need. “[Cox] has been dogged on this case and I think homeowners should be appreciative of his efforts and of Pine Tree Legal’s,” says Maine Attorney General Janet Mills.

The four major U.S. bank regulators recently announced they are conducting a joint investigation of foreclosure practices around the country, including visiting mortgage servicers and reviewing sample loan files. Cox’s work is owed much of the credit for such developments, according to Don Saunders of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association. “That case will have a dramatic impact on future litigation and on the response of the rest of the country,” he says.

For Cox, the foreclosure work is not only a challenging legal pursuit, but also a form, case by case, of some sense of redemption.“I still felt remorse to some degree for the role I felt I played in the last crunch in the ‘80s and ‘90s,” he says. “I can’t tell you how much better this feels.”

Jackie Farwell, Mainebiz staff writer, can be reached at jfarwell@mainebiz.biz.

DOWNLOAD PDFs

Read more

Comments