Bridging the skills gap

photo/TIM GREENWAY

Jay Pinkerton, former shop teacher and now head of school at Lincoln Academy, says the school's new applied technology center will serve students and the businesses that need skilled tradespeople

photo/TIM GREENWAY

Jay Pinkerton, former shop teacher and now head of school at Lincoln Academy, says the school's new applied technology center will serve students and the businesses that need skilled tradespeople

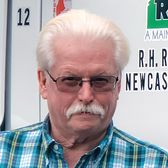

John Reny, president of R.H. Reny Inc., happens to be in the retail business, but he cares deeply about the growing applied-technology crisis in Maine.

On any given day, the 16 Renys department stores throughout the state might need a truck mechanic, a skilled electrician, a plumber or an HVAC technician, he says. If young people aren't finding their way into those trades to replace the skilled workers who've reached retirement age, Reny wonders how those necessary jobs will get done.

“You need skilled people to do that stuff,” he says.

That realization is why Reny and other business leaders in Lincoln County are behind the $1.72 million capital campaign soon to be publicly launched by Lincoln Academy to build an Applied Technology and Engineering Center at its Newcastle campus. The soft phase of the fundraising campaign recently topped the $1 million mark, assisted by a lead gift of almost $450,000 from an anonymous donor and a recent gift of $200,000.

Connecting minds to hands

“I think it's a great idea,” says Reny, an honorary Lincoln Academy trustee who's proud to note that four generations of his family have attended the private high school that provides public education for students from Bremen, Bristol, Damariscotta, Jefferson, Newcastle, Nobleboro, South Bristol and other communities in the mid-coast. “I've heard from local tradespeople who say they need young people who know how to work with their hands.”

Kathe Cheska, development director of Lincoln Academy, says the proposed applied technology and engineering center has long been identified as a need at the school, which (due to its hybrid status as a private/public school) doesn't receive taxpayer funding for capital improvements. The $1.7 million project — with $1.45 million to pay for a new building and $250,000 to equip it — depends entirely on private donations — an effort jump-started in a big way by the anonymous donor.

“This person has worked with his hands his entire life,” Cheska says. “He's been involved in the community many many years. He primarily wanted to help the local students who are going to stay here — who aren't planning on going off to college — learn the skills that will enable them to stay and make a decent living.”

Cheska says “applied technology” is the tag now being used for the kind of education that used to be called “industrial arts” or “shop class.” Since 1966, she says, those classes have been held in the basement below the Nelson Bailey Gymnasium — a work area lacking in natural light and especially noisy whenever a gym class is taking place overhead.

“It's a 'second-class citizen' facility, for sure,” she says.

The new center is slated to have an automotive and small engines lab with two floor-mounted asymmetrical lifts; a woodworking and marine technology lab for carpentry, boatbuilding and marine engines; a general lab for welding and other courses; a mechanical-drafting classroom with two-dimensional and three-dimensional computer-assisted drafting and engineering equipment; a finishing room for paints and varnishes; a reference room; and a large classroom. Currently, there is one lab, so tools and projects have to be stored away when one class ends and another begins.

Jay Pinkerton, a former shop teacher who's now the head of school at Lincoln Academy, says a state-of-the-art facility will serve an important purpose beyond the obvious ones of providing modern ventilation and lighting systems, expanded space and new equipment. It signals a strong commitment to hands-on learning and teaching skills that will be needed by Maine's manufacturing, applied technology and engineering businesses when Lincoln Academy students enter the work force.

Importantly, he says, the facility's expanded space will allow Lincoln Academy to encourage even college-bound students to take applied technology classes, thereby combating the national decline in traditional craftsmanship skills essential to manufacturing and useful for fixing leaky faucets or completing home-renovation projects.

“I know what connecting a student's mind to their hands can do,” Pinkerton says. “When you can connect what you're learning in the textbooks with what you can make or do with your hands, it's just amazing.”

Bridging the skills gap

It's no secret that Maine employers — particularly those in manufacturing, information technology, precision technology, science and engineering fields — are concerned about the gap between their needs and the skills of those entering the work force. The problem is two-fold: There is an insufficient number of young people with the traditional trade skills to replace retiring workers; there's also a lack of workers, both young and old, who are prepared to adapt their skills to the fast-changing needs of Maine manufacturers, machine shops and other applied technology firms.

Lisa Martin, executive director of the Manufacturers Association of Maine, says her group is responding to that problem by calling on industries, state government and educational institutions in Maine to collaborate on work force development issues. An emerging focus is the realization that Maine manufacturers can do a better job not only in working with schools to make sure they're teaching the skills needed now and in the future, but also in broadcasting the multiple economic benefits of those jobs.

“Manufacturing is vital to the economy, it's what brought us out of the recent recession,” she says, noting that one part of the message that should resonate with high school students is the simple statement, “Here's what they pay.”

Maine's Industry Partnership/Sector Strategy, a 37-page report released by the association in December, offers some eye-opening statistics to anyone who considers manufacturing as low-skill, blue-collar jobs that don't pay as well as typical white-collar jobs. Representative annual wages for experienced manufacturing workers in Maine are:

- Machinists: $56,908

- Welders: $49,814

- CAD design/manufacturing, CNC programmers: $45,900

- Robotics and related programming: $90,300

- Manufacturing engineers: $62,800.

All of those positions dramatically exceed the average per capita wage in Maine of $37,640 and all but CAD programmers exceed the national average of $47,140, according to the association's report. They also happen to be the jobs Maine manufacturers are reporting as going unfilled due to the lack of qualified candidates. A November 2011 poll conducted by the MAMe and sent to 165 companies, with 40 responding, showed there were 230 immediate openings for high-skilled manufacturing jobs.

Martin adds it's just as important to convey to students that those jobs require training in specific skills. That's where industry leaders can help Lincoln Academy and Maine's secondary and post-secondary public education institutions: They know where the skill gaps are and what training is required to fill the gaps.

“We can make those links,” Martin says, noting that the association's “Strategic Industry Partnership Toolkit” lays out a map for creating strong connections between Maine businesses and educational institutions to foster career awareness and increase the number of skilled workers to help manufacturers thrive.

Community support

Lincoln Academy's Pinkerton says even during its initial soft phase, the $1.7 million fundraising campaign has garnered strong support from the mid-coast region's business community. A consistent theme, he says, is that they see it as a strong affirmation of the school's long-standing commitment to serving the needs of all students, not just those who are heading to college.

“It's embedded in our mission,” he says. “Our communities appreciate the fact that we are adhering to our mission.”

Bill Morgner, president of Mid-Coast Energy Systems Inc., a Damariscotta company with more than 30 employees, is one of the local businesspeople who've encouraged Lincoln Academy's board of trustees to give the trades equal billing among students as a possible career choice. He knows from experience as a college graduate who majored in biology that having a college degree doesn't always translate to a ready job. After graduation, he worked at a local oyster farm, then was offered a job at Mid-Coast Energy Systems. He found he liked it and started taking the electrical and heating courses that gave him the technical skills he needed to advance through the ranks.

“There aren't many kids who know what they want to do at the age of 17 or 18,” he says. “If you can give them an opportunity to learn a hands-on trade — electrical work, carpentry, plumbing or welding —they can at least see the possibility of how they might be able to earn a living.”

Morgner is quick to add that applied technology is an excellent way to drive home the point that what students are learning in geometry and other math classes does have relevance in the real world. Ask any plumber or carpenter, he says.

“I told them the same thing about English classes,” Morgner says. “Can [students] write a common contract? Can they understand a common contract?”

Karen Moran, a lawyer who's a trustee and the mother of three Lincoln Academy graduates, agrees that a reaffirmation of trade skills is important, in part because so many applied technology jobs in Maine are begging for qualified applicants. But she doesn't see it as an either-or situation, reiterating the point made by Pinkerton that the Applied Technology and Engineering Center has the potential to benefit all students.

“There will be overlap between the college-bound physics class and courses taught at the center,” she says. “There's ample room for cross-over … It will enhance our math and science classes. It's so much more than 'shop class.'”

Comments