Custom wood-turning co. spices up product line

For more than 40 years, Maine Wood Concepts lingered in the background, turning hundreds of thousands of custom wooden Shaker pegs, toy wheels, dowels and other components for major game manufacturers, kitchenware makers and other customers who rarely knew the source of their products' parts. But with its purchase of Vic Firth Gourmet Kitchen Products division for upwards of $900,000 at the end of last year, Maine Wood is rebranding that company's rolling pins, salt and pepper mills and other kitchen items and striking out under its own Fletchers' Mill name.

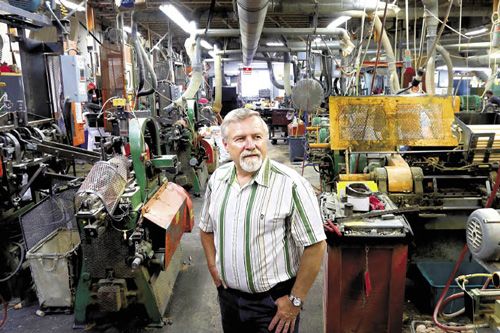

The new business could help kick up Maine Wood's revenues by 30% this year, company President Douglas Fletcher, 58, told Mainebiz in a recent interview at the company's mill in New Vineyard. He's hired 30 new workers for that business.

A key part of that town of fewer than 1,000 residents, the mill buzzes with more than 100 employees and rows of lathes, spool machines, weinig moulders, back knife machines, CNC lathes, finishing processors and tumblers turning out every sort of imaginable wooden object. Wood-turning mills use a stationary blade to cut and shape wood while it spins.

The hum of the machines is music to Fletcher's ears. But business hasn't always been that good. In the late 1990s through 2009, low-priced Chinese competitors silenced most of New England's wood-turning mills, and few came back. According to Fletcher, almost every town had a wood-turning factory in the 1970s, and now only three sizeable mills remain in Maine. They are his, Kingfield Wood Products, known for its music drum sticks, and Wells Wood Turning & Finishing Inc. of Buckfield, which gained fame for supplying about 100,000 wooden eggs for the White House Easter Egg Roll.

Nationwide, only a couple handfuls of the larger wood-turning companies remain, down from 85 mills in 2000, according to Mark Kemp, owner of wholesale crafts supplier Kemp Enterprises Inc. of Farmington, and a longtime customer of Maine Wood.

"We kept our business domestic as long as we could, to the point where the impact on us was so negative we had to go to China in 2005-2006," Kemp explains. And that included a retrenchment from Maine Wood. "At the time, a 1-inch bead would cost $60 per thousand here, but competitors in China would charge $30-$35," he says. At one point, Kemp was buying 70%-75% of his wood turnings from China, but started bringing that business back about two years ago.

Clay Smith, owner of wood parts distributor Smith Wood Products Ltd. of Fort Worth, Texas, tells a similar story.

"If Doug sold an item for $1, China was able to sell it for 50 cents," says Smith, whose father started buying wood turnings from Fletcher's father, Wayne, some three decades ago. In the mill and distribution businesses, even a five-cent difference can be huge. "If we buy 50,000 wheels from Maine Wood, we'll sell them to 1,000 or more customers, 10-20 at a time," explains Smith. And that can involve holding the inventory up to two years.

Smith notes that most wood dealers bought from China to get the lower prices. Fletcher adds that the labor rates were so low that Chinese factories could afford to have extra people sand the turned wood if it wasn't smooth enough, something that was cost-prohibitive in the United States.

Smith and Kemp note that while China's ability to produce goods improved over time, there were some issues with mold and wood splitting, since the Chinese dry wood in the sun rather than in a kiln. And while the product quality at times equaled or exceeded some U.S.-made parts, prices in China have increased in recent years due to labor shortages and higher materials and shipping costs, opening the window for distributors to return to U.S. suppliers, Smith says.

"Doug can now make an item for 95 cents, almost the same as the Chinese. His quality and ability to beat China make him very much in demand," he says.

Smith at one time bought 50% of his goods by volume from China, and that's now closer to 20%, mostly small-diameter turnings. Some 20% of Smith's catalog of parts now comes from Maine Wood, which translates into $300,000 in purchases and millions of parts, including toy wheels, the staple of the wood-turning business.

Smith says lean manufacturing — running lathes more efficiently and decreasing waste — on top of strong management, got Maine Wood through the tough times.

"They weathered the difficult times of the economy when other companies went out of business. They had a really good infrastructure and were well managed," adds Steve Parrish, vice president of sales at Westbrook-based wood products broker H.A. Stiles Co., which has been doing business with Maine Wood since its inception in 1971 and never turned to China for parts. "Five to six years ago, they probably questioned whether they could hang on. Now, business is coming back."

Trimming costs

"A lot of businesses went under during that time," Fletcher remembers of the hard times. "We didn't know if we'd stay afloat." The company went from 80 employees in the late 1990s to fewer than 50 from 2005 to 2008. Now it's at 100-plus.

Big customers like Milton Bradley Co. and Parker Brothers game makers and Mirro Foley pots and pans, which had wooden handles, went away.

"We reorganized and cut costs and did whatever we could," Fletcher says.

In May 2009, for example, it moved Pride Manufacturing's Custom Wood Turning Division, which it had acquired in 2005, from Guilford to New Vineyard, consolidating the two operations into one and eliminating duplicate staff such as an office worker and forklift driver.

Toward the end of 2009, things started turning around. From the third quarter to the end of 2009, the company was able to bring back a few accounts that it had earlier lost to China, a trend that continued in 2010 and 2011.

But it wasn't just the Chinese nibbling away at its business. Consumer buying habits had changed, high school home economics and shop classes were cut back and electronic gaming on systems like Xbox had replaced home craft-making.

"In the 1980s and 1990s, distributors were doing triple to quadruple [the business] they are doing today," Smith remembers. "Now there are gaming systems, and schools no longer have wood shops. The American crafter is no longer in demand."

But he sees signs of a modest rebirth of the industry. He points to craft website Etsy.com for sparking a great trend and the popularity of weekend craft shows among hobbyists. Also helping bring parents back to American toys for their kids are health scares such as the lead and other toxic substances that were found in toys made in Asia.

Growth by acquisition

Maine Wood was an early adopter of lean manufacturing practices, and has used strategic acquisitions to grow its business. When Fletcher's father and uncle Earl bought the mill from Percy Webber, its former operator, in 1971, they bought it for less than $100,000.

His dad and uncle were both master mechanics before they became managers, which was key to Maine Wood's business.

"They needed to be mechanically minded from the get-go to compete," he says. "They devised a way to use fewer machines and to use less wood before doing that became popular."

Their first customer was a local wood-turning company called Frary Wood Turning Co. that had too much work, so Maine Wood took the excess business. When Frary burned down, Maine Wood looked for other opportunities.

Fletcher says Maine Wood, which he runs with his two brothers, vice president of operations Jody and vice president of product development Gary, looked to acquire other companies to branch out through the years. The first was a machine shop in Ashburnham, Mass., bought in the mid 1990s, which it ran a number of years until 2005 and then sold to his uncle. That shop made knives and cutter heads for factory equipment, including that at Maine Wood.

In 2005, Maine Wood paid about $500,000 to buy the name, inventory and customer list for a file handle it had been making for Lutz File & Tool Co. of Cincinnati. That same year it paid more than $750,000 for Pride Manufacturing's Custom Wood Turning Division, which made smaller scale wood turnings such as pieces for game boards, and paid an undisclosed amount for Downeast Woodcraft, an Anson-based maker of cooking spatula handles. There were some smaller purchases as well, but the next large one came at the end of 2012, when it bought Vic Firth Gourmet division for upwards of $900,000.

Before Vic Firth, the only retail item Maine Wood sold was the Lutz file handles. But the Vic Firth purchase let it establish its own brand, Fletchers' Mill. Apart from giving Maine Wood a brand name product, the Vic Firth line is expected to add 30% to sales in dollars by the end of 2013, Fletcher says, and it gives the company a higher-end product that can significantly improve its profit margin. The Fletchers' Mill, nee Vic Firth line, is sold by Williams-Sonoma, Crate & Barrel and other retailers. Maine Wood's revenues overall were $5 million before the Vic Firth purchase. The company also grew 30% last year from its new molding and turning business. Maine Wood also has been selling internationally over the past five years.

Changing Vic Firth's brand to Fletchers' Mill has proven to be a challenge. The first question was about quality, Fletcher says. Maine Wood hired Vic Firth's sales and marketing manager on the gourmet line, which helped assure the large clients that the quality would remain high. Fletcher says the "Made in Maine" label also made a big difference. The other problem was that some vendors with Vic Firth stock wanted Maine Wood to help pay for discount sell-offs of the product that was still in stock. Maine Wood will pay a sales commission on Vic Firth products over a period of time, so Fletcher expects the final cost of the acquisition to be $800,000 to $900,000.

Other acquisitions are likely, but Fletcher doesn't want to talk about them or about any niches he hopes to fill. Fletchers' Mill is a critical part of his business going forward, and he expects substantial growth. He's already struggling to keep up with demand, and says he's contemplating how to handle that, perhaps by a second shift or improved equipment. Already, 20% of his payroll is for overtime work. Business in every division is steady, including promotional items like yoyos and wooden nickels. Maine Wood makes 12 million wooden nickels a year, making it a world leader.

Comments