Orono incubator amasses innovative companies

At first glance, the Target Technology Incubator in Orono looks like any other modest, one-story building in an industrial park. But within its white and grey clapboard siding, startup companies are developing ceramic water filters, composite bridges, high-temperature wireless sensors, odor-control paper and a mobile application for sports goalies, innovations that might one day drive economic development in the Bangor area and root Maine's young entrepreneurs to build new companies here.

Early successes are evident. Take Emma Wilson, 21, a rising senior at the University of Maine in Orono, who fully expected she would have to leave the state to get a good job after graduating next May. Then she discovered the Innovate for Maine program, which opened the door to a paid summer internship with Zeomatrix LLC, a Target Technology Incubator tenant that is developing value-added, odor-control paper products.

Wilson has been applying her major in management and marketing to one of Zeomatrix's forthcoming products, a biodegradable and odor-control cat litter bag. She's performing market research, competitive analysis, pricing research and sales forecasting as well as looking into crowd funding. She hopes to continue working there a few hours a week this fall.

“This takes my coursework into the real world. It's been eye-opening,” says Wilson. “I thought I couldn't live in Maine and get a good-paying job. But there are opportunities for jobs in Maine.” Before starting the internship, she planned to go to Boston to work for a marketing firm. Now, she plans to go to graduate school, possibly outside Maine, but ultimately to return to the state to work.

That's just the kind of story Evan Richert, Orono's town planner, wants to hear more frequently.

“We want to keep more young people in Maine,” Richert says. “The end game is to develop enterprises that can grow.”

Those enterprises can originate from efforts as simple as spreading high-speed Internet throughout the state to spark new home businesses all the way to setting up innovation centers like the Target Technology Incubator.

“You never know where it will come from,” Richert says of sparking innovation. “You need to plant a lot of seeds.”

And it requires patience and persistence. Richert estimates it will take at least a generation for today's innovation seedlings, like those in the incubator, to fully bloom. He points to Research Triangle Park in North Carolina, which was created in 1959, but didn't take off until the 1980s, when pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline set up there. It is now the largest research park in the world, with 170 companies.

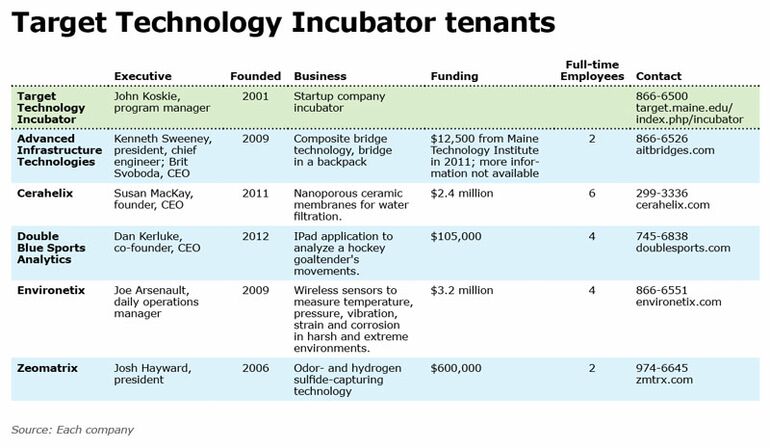

The Target Technology Incubator, by contrast, has five startup and four more-developed “market” tenant companies within its 20,000-square-foot building. But Richert remains optimistic.

“A lot of work is beginning to transfer into the economy and jobs,” he says.

But simply counting the number of new jobs doesn't give the whole picture when it comes to the impact of startup companies on economic development. The kinds of jobs and the wealth created through them are important metrics as well, says Renee Kelly, co-director of the University of Maine's Foster Center for Student Innovation in Orono. “And companies are being created with headquarters in Maine.” Kelly also is director of economic development initiatives for the university and is involved in administering the incubator.

Homegrown expertise

The Target Technology Incubator has its roots in the late 1990s, when legislators and organizations around Maine sought ways to spur innovation as a means of improving individual earning power with better jobs, boosting regional economic development and elevating the University of Maine's standing as a research university.

In 1999, Maine ranked 45th in the United States in total research and development as a percent of gross state product, according to the 2012 Maine Innovation Index. State funding then was paltry at about $3 million annually. By 2008, the latest figures available, the state improved its ranking to 35th, and had maintained annual state R&D investment levels topping $20 million since 2000, due in part to some major R&D bonds. But funding has been stale since then, with Gov. Paul LePage vetoing a $20 million R&D bond in 2012 that would have replenished the Maine Technology Asset Fund.

The Target Technology Center was one of the first four designated Applied Technology Development Centers to be established in Maine. The initial idea was to place seven industrial sectors identified as targets for growth around the state. But thin resources have left only three, the University of Maine's Target Technology Center, which houses the incubator; the Maine Aquaculture Innovation Center; and the Maine Center for Entrepreneurial Development. In February 2012 the three formed the Maine Business Incubation System, a vehicle by which they can collaborate and help entrepreneurs, including in the incubator, with resources inside and outside of Maine. MeBIS is funded by the Maine Technology Institute and the Blackstone Charitable Foundation.

“The incubator is one manifestation of the growth of R&D in the University of Maine system, which has made a big difference to this region of the state,” explains Richert. “This [area] can look at itself as a region with an innovative dimension to it.”

Richert characterized the seven-incubator effort as wishful thinking to some degree, as many were located in areas of the state without enough resources to support them. The Target Technology Incubator, by contrast, is next to the state's flagship R&D university.

“The issue is always sustaining the commercialization of R&D. It takes so long before it becomes self-generating,” he says.

While the Target Technology Incubator originally was the information technology sector incubator, it has evolved beyond that, having extensive ties to various parts of the University of Maine. Most of the incubator companies have either spun out of the university or license its technology.

“An entrepreneur is place-based,” adds Kelly of the University of Maine. “Their resources are in a particular place.” The incubator already is looking for space nearby to set up a second phase that, among other things, could house a possible wet lab and provide space for companies that have outgrown the current incubator.

The companies in the incubator are all early stage and looking to get to commercialization or are just recently selling products, so it's difficult to come by metrics such as jobs created and follow-on businesses. But Richert says there are huge intangible benefits to having the incubator and university located in such close proximity.

“It's a stepping stone from the university to the world of business,” he says. “The push to ramp up the status of research at the University of Maine and in the state started only about 15 years ago. Companies still need to get through the valley of death,” moving to and financing commercialization.

The incubator is a joint effort of the Bangor Target Development Corp., which owns the facility, the University of Maine, the state of Maine and the city of Orono. It currently has five startup tenants: Advanced Infrastructure Technologies, which makes the “bridge in a backpack;” Cerahelix, which makes water filters; Double Blue Sports, the newest tenant with an iPad app to help hockey goalies; Environetix Technologies Corp., which makes high-temperature sensors; and Zeomatrix, which makes odor-suppressing paper products. They start by paying 80% of the normal rent, which is increased 5% a year until they reach the full, market-tenant rate. The incubator also has four market tenants that pay the full rent.

A place to hang your hat

For startup tenants, the incubator provides offices, a shared kitchen and conference rooms, shared printers and copiers, as well as collegial support from inside and outside the incubator. One example is the monthly Lunch and Learn series that brings experts in to discuss common topics such as how to build a management team for scalable technology businesses. Another is access to resources at the University of Maine that they otherwise couldn't afford, such as a multi-million-dollar cleanroom. That is a separate fee. Just as importantly, they are around other entrepreneurs going through similar experiences.

“Incubation isn't about just a space,” says Jesse Moriarity of the Foster Center. “It's about being around other people, and looking for help, expertise.”

While she and others involved in administering the incubator don't judge the ideas of the startups, they do try to steer the companies so they can learn without investing too much, and “fail fast, fail cheap,” she says. “We look at how passionate you are about this idea. Did you just come up with this in the shower? Do you feel strongly enough about this to not get paid for two-to-three years?” she says, noting that she encourages would-be entrepreneurs to watch “The Social Network,” the movie about how Facebook started.

Such advice in an incubator setting has been a lifeline for the newest tenant, Double Blue Sports.

“This really gives us an opportunity to build a company,” says Dan Kerluke, co-founder and CEO, and a former University of Maine hockey team associate head coach. “I wasn't a business major. I love being in the incubator. People can provide assistance if we need it. If I were downtown, I'd feel lonely.” Double Blue Sports pays $350 per month, including the MeBIS membership.

The company plans in mid-August to start selling its advanced video and analytics Apple iOS app to help ice hockey goalies improve their performance, and expand to other platforms later. Kerluke says it could especially be helpful with the size reduction in National Hockey League goalie pads expected this coming hockey season. The smaller pads potentially could allow more goals.

The app, called 360 Save Review System or 360 SRS, stores video from GoPro or other point-of-view cameras in the cloud. It can be used by hockey goalies on all levels, as well as goalies in soccer, lacrosse and field hockey. Currently, the goaltending metrics that do exist are from video that can take hours to scan, arrange and analyze, he says, while his company's program can look for key goaltending sequences within seconds.

“Goaltending is millimeters. It's more technical than any other position in sports,” he explains. The app will sell for $375 for 20 games of cloud storage, $425 for 40 games and $475 for 60 games. Kerluke says those prices make it affordable to everyone.

Kerluke found out about the incubator the way a lot of information travels in the startup community: by word of mouth. His daughter is in the same day care as Moriarity's child. He credits Moriarity with pointing the company in the right direction, including helping it find a lawyer.

He also sees advantages to locating in Maine. “The experience is more personalized,” says the Toronto native. “We wouldn't have gotten this type of guidance in Toronto.”

Zeomatrix also benefited from the incubator and its network of collaborators, including MTI.

“For us, the incubator allowed Zeomatrix to retain communication with MTI,” says Joshua Hayward, who was hired as the company's president last year to recast its focus, and who works for sweat equity. The connection with MTI led to finding a way to fund a study about its primary product at the time, a biodegradable tarp that reduces odors in landfills.

“That study helped us identify the challenges of the paper application in the landfill use,” he says. “It helped us determine the underlying cost of this paper was too high, and as a result we sought an alternative opportunity.”

That is with a mill in Massachusetts Zeomatrix it is currently negotiating with to produce a lower-cost eco-friendly paper made from waste paper. And the company is shifting its focus toward making a biodegradable, anti-odor paper bag for curb-side garbage pickup, a hot trend in major cities.

Leveraging resources

Guidance can come from many sources, including other entrepreneurs like Susan MacKay, who with her second startup, is the incubator's only serial entrepreneur. She's been generous with sharing her experiences with the other tenants. MacKay's first company, fellow incubator tenant Zeomatrix, was separated from her new venture, Cerahelix, in 2011.

Cerahelix is now testing its ceramic water filter, and hopes to have it ready for the market in pilot scale in late 2014, and for large commercial scale in a couple years. For MacKay, the incubator is important because it offered subsidized space and shared resources.

“That is huge for us. And this site is on fiber optics because a supercomputer was here. We collaborate with Europe and other parts of the country,” she says.

For MacKay, it's also an opening to get leads and introductions from the University of Maine. Kenneth Sweeney, the new president of Advanced Infrastructure Technologies, which makes the “bridge in a backpack,” also values the proximity of the university.

“Being this close to the university is a big deal,” says Sweeney, who joined the company in July after spending 35 years with Maine's Department of Transportation, most recently as chief engineer. It's only a 10-minute drive. The bridge company contracts with the university for a certain amount of time to access its facilities, and then pays a separate fee for any testing services.

The company's technology, a composite carbon fiber tube filled with concrete, already has been used in more than a dozen bridges in Maine and elsewhere. Sweeney has ambitious plans for the company.

“My goal is to see the company move from a startup to be on the front line in the bridge business,” he says. “It will take three-to-four years.” Meantime, by the end of 2014 he expects the company to have a substantial number of bridges built.

Fellow incubator tenant Environetix also is happy to have the university and its labs nearby. The University of Maine spinoff makes sensors that can measure high temperatures, strain and pressure in engines, power plants and other harsh environments.

“We couldn't possibly afford the $5 million to $10 million cleanroom facility,” says Don McCann, technical manager and senior project engineer at Environetix. “The monthly fee to use the equipment is reasonable.”

The company recently tested its technology on an operational helicopter engine for General Electric in Albany. Such engines are used in Blackhawk and Apache helicopters. The sensors can sit on rotating parts and other places. They are wireless and battery-free. The idea is to measure strain and temperature to assure the engine does not fail rather than just checking the engine at regular intervals. Called condition-based maintenance (when the need arises), that strategy could result in big cost-savings.

“Airlines can save a lot, hundreds of millions of dollars a year,” McCann explains. Environetix is in the process of negotiating some big contracts now, even though it is still moving from the prototype to commercial stage. Because the University of Maine can make 10,000 sensors each year, the company plans to use that service for its first five years of production.

And like the University of Maine's Wilson, McCann is a Maine native who decided to come back to the state after getting his undergraduate degree from Cornell University. He returned to both work in Maine and get his PhD from the University of Maine.

“This model can work,” he says of the incubator. “One of things we need in this state is technology. And having a tech hub like a university is key to having infrastructure. Eventually more students will understand there is an opportunity to start a small company here.”

Read more

Entrepreneurs, funders to meet at ‘matchmaking’ event

Cerahelix raises funds in equity offering

Mainebiz Women to Watch alumni: Checking in on past winners

Comments