Tiny lots, big ideas fueled by Portland housing crunch

Photo / Tim Greenway

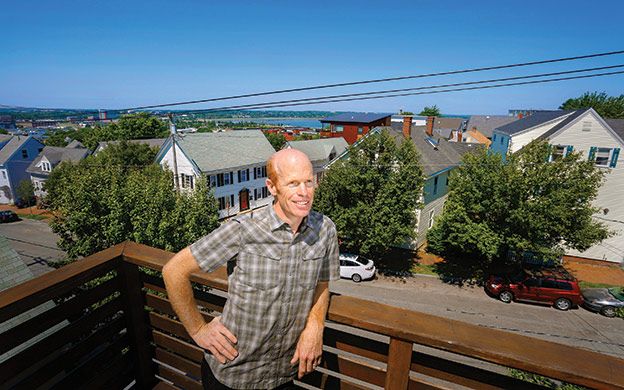

Jesse Thompson, principal of Kaplan Thompson Architects, on a deck on Cumberland Avenue on Munjoy Hill, one of several areas of Portland that has seen infill of construction on vacant or underused lots.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Jesse Thompson, principal of Kaplan Thompson Architects, on a deck on Cumberland Avenue on Munjoy Hill, one of several areas of Portland that has seen infill of construction on vacant or underused lots.

Five years ago, Paul Ledman and his wife Colleen Myers decided to move their family to Portland from Cape Elizabeth.

They wanted to be in the city, and they wanted to design a house with several missions in mind — it would be energy-efficient, provide rental income, be a solid investment in a desirable neighborhood and have a garage and an elevator so that they could age in place.

Ledman, who is not a developer but has been involved with real estate for many years, came up with a design for a three-story apartment project and found a tiny infill lot to buy for $130,000. Located at 62 Cumberland Ave. on Munjoy Hill, the 5,000-square-foot lot had apparently been vacant “as far back as we can tell,” Ledman says. “I have a photo of this area taken after the fire of 1866, and this little spot has nothing on it, no foundation, no ruins. We think it was just a small lot tucked in there and was probably just sitting there, and no one thought to do anything here.”

Ledman found the lot after the city of Portland made a zoning change that allowed developers to allot just one off-street parking spot per apartment, rather than two. That change was one of a series that made it possible for developers to view tiny lots scattered around the city as potential sites for new development. Given this lot's tight confines, more than one parking space per apartment would have made his dream project difficult, says Ledman. But the lot was just big enough to accommodate the building — a two-story owner's apartment on top and two rental apartments, driveway and three-car garage underneath. Designed by Kaplan Thompson Architects, the house has, since completion five years ago, become known as one of the most high-tech buildings in Maine, with a highly insulated envelope, photovoltaic array and solar hot water tubes, resulting in average energy costs of about $1 per day for the owners' unit.

Like all city buildings, says Ledman, construction involved strategy, given the lack of stowage.

“You order pieces, you plan your day well, you use the material you ordered, and then you get more material,” he says. Plus, construction for this project occurred during a winter of particularly heavy snowfall.

“We shoveled in the morning and worked in afternoon,” he says. “It can get crowded. You do what have to do.”

Tiny lots are hot property

Thanks to revised zoning regulations, lots once deemed too small are becoming hot property.

In 2015, Portland's City Council approved amendments to the city's R-6 Residential Zone. R6 is the city's designation for the dominant residential zone on the peninsula, the historic core of the city, says Senior Planner Christine Grimando. There's some R-6 zoning off-peninsula, but most R-6 areas are on-peninsula. That includes most of Munjoy Hill, a big portion of East Bayside, Parkside and West End and parts of Libbytown and East Bayside.

Amendments included reduced minimum lot size, reduced front setbacks, lower minimum lot area-per-dwelling unit, higher allowable lot coverage (from 40-50% to 60%) and the changed parking standards.

Before the amendments, minimum lot size of 4,500 square feet made over 70% of existing parcels in R-6 nonconforming, rendering many lots undevelopable. Yet city officials felt development on small lots had potential.

“We realized we had a big gap in these residential neighborhoods, which had a lot of variety and were loved and successful,” says Grimando. “The pattern is largely set in those neighborhoods — they're built and established. But there's still incremental change — there's still vacant land, there are structures that get modified, or that fall down or get taken down. So we knew we had very small parcels, but the zone wouldn't allow them to be developed. These amendments allowed small parcels to develop in much the existing land use pattern that historically formed these neighborhoods.”

The minimum lot area was reduced to 2,000 square feet — meaning that more than 80% of the previously nonconforming lots now conform to zoning. There's also greater flexibility for existing homeowners to build small additions.

“It adds to the diversity of the housing stock by allowing those kinds of projects to happen,” she says. “We've long had policies in place that support diversity in housing and walkable neighborhoods, and allowing infill helps those goals.”

The city also approved amendments to its business zones to allow more building flexibility and greater density along certain transit corridors, Grimando says. A couple of recent mixed-use commercial and apartment projects are at West End Place at the corner of Pine and Brackett streets, and 89 Anderson St. in East Bayside. The former is a 39-unit market-rate housing project with first-floor retail spaces and inside parking. The latter, by Portland developer Redfern Properties, is a 53-unit market-rate apartment complex, with first-floor retail and restaurant space.

Public response overall has been positive, says Grimando. The city heard concerns when amendments were drafted over the course of the extensive community engagement that preceded the changes. But “people also offered constructive feedback,” she says. “There was a lot of support.”

Tiny postage stamps

“The lots are all tiny,” says Kaplan Thompson principal Jesse Thompson. “But the really interesting story is that we always used to do this in our cities. If you walk around Portland, all the older buildings are tight together on tiny lots. All the buildings that everyone loves are on these tiny postage stamps.”

Thompson says his firm has done a number of infills around Portland. Projects include a three-unit townhouse rental in the West End and the four-story, 45-unit affordable housing project, Bayside Anchor, under construction on 20,000 square feet at 81 East Oxford St. in Bayside.

Urban renewal is to blame for zoning regulations that restricted construction to larger lots.

“It seems like people thought the city was too cramped,” Thompson says. “And when buildings were taken down, the land was turned into parking lots. Parking is incredibly profitable, and building buildings is risky and expensive.”

It's all part of the new urbanism movement, says Daniel Diffin, a principal at Sevee & Maher Engineers Inc.

“My understanding is the younger generation is more interested in living in a downtown area where you can walk to grocery stores, markets, restaurants, clubs and bars,” says Diffin. “So there's a lot of pressure from younger generations moving back into the city. At the same time, a lot of older people, who moved out of the city to suburban houses, are downsizing and also want the same walkability to resources and entertainment.”

A couple of Portland infills currently on Sevee & Maher's docket involve vacant lots or old buildings that are losing value due to dilapidation.

“Our client wants to tear the old buildings down and build higher-value housing,” says Diffin. “There's also a lot of pressure on vacant spaces to be developed as modernized housing, either for rent or purchase.”

Sevee & Maher has been involved in infills elsewhere, including a senior apartment building for Avesta Housing in Gorham. Another in Yarmouth is planned on an already built-out senior apartment space.

At the Portland firm Archetype Architects, David Lloyd designed a number of infills that are under construction. They include a four-family condominium on 3,000 square feet on Saint Lawrence Street and an eight-unit condo on the corner of Fore and India streets. Lloyd's own house, at 29 Waterville St., is an infill of 3,000 square feet.

From an architectural standpoint, infill buildings are not difficult to draw, says Lloyd.

“But they're all challenging in the sense that you're fitting into an existing urban context,” he says. “You want to do something that reflects today's architecture but is also respectful to the surrounding fabric of the neighborhood.”

Portland has plenty of potential for infill, says Thompson.

“A lot of land has been ignored,” he says. “There are a lot of parking lots. So there's lots of room. Every place there's a parking lot, there was once a building.”

Read more

Cooperative building Bar Harbor solar farm

Maine home sales see slight dip from 2015

Portland Mayor Strimling proposes new landlord restrictions

Portland real estate still hot, so where's the best place in Maine to get a home loan?

Comments