#MBNext16: Melik Peter Khoury is an agent of change at 'America's Environmental College'

Photo / Peter Van Allen

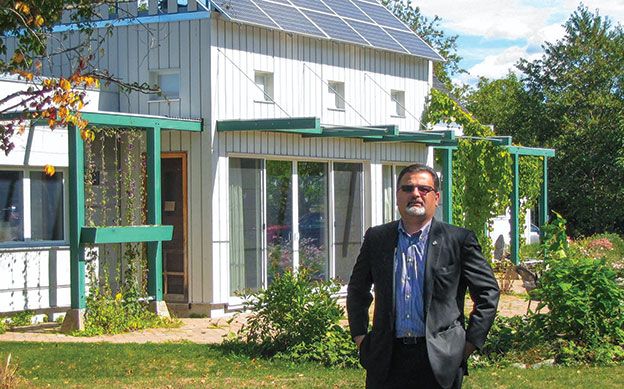

Melik Peter Khoury, president of Unity College, is raising the profile of the college at a time when it is adding buildings and welcoming record attendance.

Photo / Peter Van Allen

Melik Peter Khoury, president of Unity College, is raising the profile of the college at a time when it is adding buildings and welcoming record attendance.

Melik Peter Khoury is an academic with an unorthodox academic background. He's a self-described agent of change in a world of higher education that's not always eager to move forward.

Yet at Unity College, which bills itself as America's environmental college, he is right at home.

Khoury, who joined the college in 2013, served as interim president for more than a year before finally officially taking over the role before the start of the recent academic year. He was just in time to usher in the largest group of students in the college's five-decade history, 700 undergraduates, and to cut the ribbons on two LEED-certified campus buildings.

Drawing on multiple cultures — and television

Khoury, 43, is married, has two grown sons and lives in China, about 20 minutes from the Unity campus.

He spent his formative years in West Africa. He was born in Sierra Leone to an English mother and a Lebanese father. At the age of 3 the family moved to Gambia. His family was in the hospitality business. When political tensions in Gambia flared, he was 21 and eager to move to America.

“It's a funny story. I loved 'M*A*S*H*' and Major Pierce was from Crabapple Cove, Maine. I wanted to go to Maine,” he says.

Though Crabapple Cove was a fictional town (according to one account, based on Bremen), he wanted to settle in a place that conjured that image. It was between Machias and Fort Kent and he chose the latter, forging a life in Aroostook County. He graduated from University of Maine at Fort Kent and started on his journey into academia.

“I still consider myself a County boy,” he says.

Growth and sustainability

Unity, which was founded in 1965, takes its role as an environmental college seriously. It has 16 undergraduate majors, all in environmental fields, including wildlife biology, sustainable energy management, conservation law enforcement, sustainable agriculture and environmental writing and media studies. Students live in dorms that are heated by sustainable sources. (Unity was the first college in the nation to divest its endowment of fossil-fuel stocks.) Students are encouraged to get experience in the field. On a recent field trip, students were bused to the new Katahdin Woods and Water National Monument.

“If you want to work in the environmental field, start here,” he says. “You'll do primary research. You don't just sit in the classroom. We're innovative.”

Many of Unity's peer colleges founded in the 1960s were built on being at the fringe of society or outside of society. Unity wants to train people to work on some of the world's most vexing issues, those with an environmental core. Khoury says the point is not to convince anyone about climate change. Rather, it's to ask questions, create solutions and place graduates in good jobs.

“We're an environmental college. Some people think we're about activism, but we're about common sense,” he says. “People are beginning to realize the earth is a finite resource. But our students range from environmentalists to conservationists. We encompass 'huggers' to hunters.”

Seventy percent of students are from out of state. When they apply to Unity, they may also be looking at University of Maine in Orono, Green Mountain College in Vermont, Paul Smith's College in upstate New York, Northland College in Wisconsin or Prescott College in Arizona.

From Day I, Khoury says students are encouraged to look at as many perspectives as possible. On the day Mainebiz visited the campus, Khoury happened to be introducing Lucas St. Clair, who was giving a talk on how the Katahdin Woods and Water National Monument took shape.

“Families invest to send students here. We owe it to them to give them more than a credential,” he says. “I tell our students to talk to people on all sides. You're not going to become Lucas St. Clair if all you do is talk to people who agree with you.”

On a tour of the campus, Khoury expresses pride in what's new: Five new buildings have opened in four years. Each has an environmental story to tell: Clifford Hall is a residential building heated with biomass pellets, Unity 2 is warmed by heat pumps and so on. Khoury had the president's house, already outfitted with solar panels, converted to an academic building.

The new buildings were paid for with bonds, operating dollars and cash reserves.

“We are building the infrastructure. We're becoming an economic driver in Maine,” Khoury says. “Maine has 'Vacationland.' I want Maine to become 'Educationland.'”

Infrastructure is a word Khoury uses frequently. He includes in the definition fiscal strength; the physical aspects of the campus, including buildings and the outdoors; up-to-date technology; and humans — the faculty and staff.

“That will lead to academic excellence, fundraising success and higher enrollment,” he says.

He describes himself as a non-traditional academic. One of his degrees is from the University of Phoenix.

“I've been hired into newly created positions. I see it as a sign higher education needed to change. I've been brought in to be a change agent,” Khoury says. But one way to change things is by lending an ear.

“This is going to sound weird, but listening to people is really important,” he says.

Often change can be scary.

“Until people see how they fit into that change, change dies. You have to build trust,” Khoury says.

He cites an example when he discussed restructuring a department. “People hear 'restructuring' and they think layoffs. But we added 25 positions,” he says.

Khoury has already been successful in bringing in donations to the college. Gifts often come from “people who are not alums, but they believe in what we're doing. It's less about donations and more about investment and partnership,” he says. “We're not getting $1 million checks. We're doing all of this on the margin.”

Read more

Unity College unveils $6 million expansion plan

College cuts energy usage and costs

Unity College student lands $50K federal research fellowship

Unity College appoints interim president as permanent head

UNE among Maine schools named in U.S. News and World Report's 'Regional Universities North'

Unity College: High demand leads to ‘instant admissions day’

#MBNext16: As craft brewing evolves, Sean Sullivan aims to keep Maine at its forefront

#MBNext16: Emily Smith proudly expands a sixth generational Aroostook legacy

#MBNext16: James McKenna keeps Maine's diverse economy connected

#MBNext16: Charlotte Mace is driven to cement Maine's place in a biobased future

#MBNext16: Brian Corcoran brings thousands of people — and millions of dollars — to Maine

#MBNext16: Tom Adams globally exports an iconic Maine brand

#MBNext16: Elaine Abbott's role in Eastport goes beyond managing a Downeast destination

#MBNext16: After fulfilling a five year dream, Lucas St. Clair still looks to the future

#MBNext16: Emily Smith proudly expands a sixth generational Aroostook legacy

#MBNext16: James McKenna keeps Maine's diverse economy connected

#MBNext16: Charlotte Mace is driven to cement Maine's place in a biobased future

#MBNext16: Brian Corcoran brings thousands of people — and millions of dollars — to Maine

#MBNext16: Tom Adams globally exports an iconic Maine brand

Maine flexes environmental muscles in 'Top 50 Green Colleges' list

Comments