Base price | The $891M hole it will leave in Maine's economy begs the question for Brunswick Naval Air Station: What's next?

Steve Levesque, executive director of the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority, is navigating his Ford Escape along Brunswick Naval Air Station’s network of roads, slowing to point out significant features and what they could become. There’s the 250-room hotel that could become a conference center. And there’s the wing command control room, with IT capabilities so confidential that all Levesque will say is it would be an ideal data center. Levesque stops at a cluster of buildings to describe how they could become a college campus, the nearby 76 suites of officers’ quarters the perfect dorm rooms.

“It’s an exciting foundation for what we could support from an economic development perspective,” he says.

Levesque, once the head of a management consulting firm and commissioner of the Department of Economic and Community Development under Gov. Angus King, has since 2005 been leading the efforts to redevelop the naval base once it’s fully decommissioned in May 2011. Lately, he’s been marketing the property to businesses, and he can detail its assets in specific numbers from memory: over 200 buildings and 1.8 million square feet of space. Number of units in the new barracks? 190. Cost to build a base just like it today? $2 billion to $4 billion.

From the top of the airport’s old control tower, Levesque spouts off numbers, pointing to the buildings below. As he watches soldiers on the ground guide two P-3s into the hangar, a bit of awe creeps into his voice. “I could sit up here for hours.”

On that day in mid-November, it was one of the few remaining days the base would look like that, with troops in blue digital camouflage directing the P-3s and milling about in the hangar. The base’s five active-duty squadrons have all left, the last one scheduled to depart by the end of the month, deployed to Central America, Europe and Africa. The airfield and its buildings will be closed by the end of January, and the rest of the 3,200-acre property will be phased out over the next 16 months.

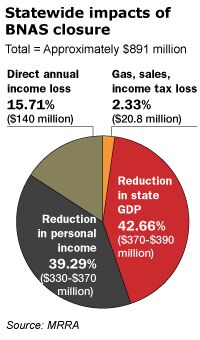

With its closure, BNAS is removing 6,500 military and civilian jobs statewide that generated over $187 million in regional economic impact. It’s a big loss for the Midcoast area, where population growth has outpaced statewide levels since 2000. It’s also a big hit for the state, since 70% of the state’s work force lives within a 30-mile radius of Brunswick. The state is losing $20 million a year in income tax revenues from those lost jobs, Levesque says, and companies statewide that provided construction work and other services are losing money, too. “I think the Legislature and the governor recognize that this isn’t just a southern Maine issue, this is really a statewide issue,” he says.

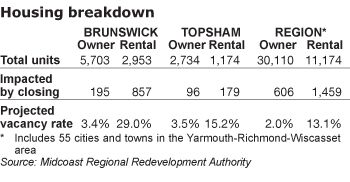

But while Brunswick and neighboring Topsham — also dealing with reuse questions, since it’s home to a 74-acre, mostly residential chunk of base property known as the Topsham Annex — grapple with the short-term impacts of losing a significant economic base, officials are also looking to the future and its new life as something else.

What that something else will be is mostly unknown, but Levesque and others have some ideas. Levesque has been touting the property’s potential and has gotten inquiries from over 50 companies, he says, most in the aerospace, composites, energy and manufacturing sectors. “We have the opportunity to lead the way in Maine in new areas, like renewable energy and aerospace clusters,” he says. “There’s nothing really like it in the Northeast, and we have opportunity here, we have the foundation to build something pretty special here — it just takes hard work and time.”

Chuck Lawton, chief economist at Planning Decisions Inc. in South Portland, calls the redevelopment of BNAS “the biggest opportunity in Maine,” one that could drive the future of Maine’s economy. To prevent job loss, and keep and attract the working-age population, Maine’s economy needs to shift from a traditional industrial base, like paper and textiles, to a creative-based economy, Lawton says. The base property would succeed by becoming the hub of collaboration between industry associations and higher education institutions, as well as a test site for energy research, he says.

“Establishing links between there and research centers like the University of Maine, Boston and Dartmouth would represent the best chance to get jobs that have a future in Maine,” Lawton says. “Growing the Brunswick area, the greater Portland area, is the best way to grow Maine.”

Aviation/aeronautics

ASSETS:

1,500 acres

Two 8,000-foot runways with 4.5 million square feet of taxiway space

Three hangars with 500,000 square feet of hangar space

Jet engine testing and maintenance facilities

New instrument landing system, built in June 2006

Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University on the property

MRRA’s “primary effort” for redevelopment is the base’s airport and aviation facilities, simply because that property will be vacated and become available first, says Levesque. The airport will be decommissioned by Jan. 29, 2010, and MRRA is currently submitting an application with the FAA to take control of the property in what’s known as a public benefit conveyance. MRRA is also working to determine a fixed-base operator, a company that would run the airport’s operations. The transportation bond just passed this month includes $500,000 for the redevelopment of the airport.

MRRA hopes to take control of the airport by next summer, at which time the organization will have to begin paying for its maintenance, so finding a business to lease the space is critical, Levesque says. MRRA is in talks with aircraft refurbishing company Oxford Aviation, which has said it would create 200 jobs at the base, but no lease agreement has been finalized. Other firms have expressed interest in the airport property as well, Levesque says.

The airport property consists of three major hangars, including one known as Hangar 6. Built in 2005, it was the Navy’s most modern hangar until it built a new one in Jacksonville, Fla., to house the P-3 planes that are transferring from Brunswick. The hangar can accommodate 850 people with office and shop space, and at full build-out, aviation-related businesses could generate up to 3,200 jobs.

The base already has one confirmed aviation tenant — the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, which has offered classes for military personnel there since 1994 and will expand to offer classes to the public.

Without enough demand for a full-scale passenger airport in Brunswick, reuse efforts have focused on industries like aircraft repair and refurbishing. Bob Ziegelaar, senior projects manager at Telford Aviation in Bangor, helped draft a strategic plan for the airport about two years ago, and says there’s opportunity in aircraft modification and construction, like installing new cockpits. He also wouldn’t preclude some type of passenger service in the air taxi industry. “Brunswick could play a role in that market, which is still undeveloped, but it will develop,” he says.

Economist Lawton envisions something more high-tech, like a company that could develop a jet engine that would operate more efficiently and use less fuel. “It’s something the industry is spending millions on, and the sort of activity I think Brunswick could make an effort to attract there.”

There’s also an opportunity to develop the unmanned aircraft sector, a controversial topic among local residents but an area that has major growth potential, says Cathy Renault, director of the Maine Office of Innovation. “That’s leading edge technology, and we’re well-positioned to take advantage of it,” she says. “From a pure technology point of view, it would mean good jobs to do that kind of R&D.”

Education

ASSETS:

Several buildings grouped together in a campus-like setting

76 officers’ quarters to function as dorm rooms

Proximity to major engineering employer Bath Iron Works, composites companies

Embry-Riddle on the base, SMCC’s composites center in Brunswick

The redeveloped base could be home to a unique educational-commercial venture where companies have access to training opportunities for their workers, and students have job opportunities nearby. While this type of model has been done elsewhere in the country, it’s new to Maine, says Lawton, and an important step in building the future of Maine’s creative-based economy. “The idea of people being trained on site as part of an investment is what the auto companies, the computer companies have done, and I think this is an opportunity for Maine to participate in that game,” he says.

When the opportunity to locate at the base came up, both Southern Maine Community College and the University of Maine jumped at it, say school officials. Together, the schools will launch the Maine Applied Technology and Engineering Center, a 14-acre campus that will focus on engineering, advanced technology and health sciences. Four buildings, including a medical center, have already been set aside for the project, and a bond package on the June 2010 ballot would allocate $4.7 million for the project.

SMCC will offer a two-year pre-engineering program that will feed into UMaine’s four-year degree, and also relocate its Maine Advanced Technology Center from another Brunswick location. UMaine plans to offer masters degrees in civil and mechanical engineering, and information systems, says Dana Humphrey, dean of engineering.

The project allows SMCC, whose South Portland campus has been bursting at the seams, to serve more students, and UMaine to expand its engineering program to students in the Midcoast and southern Maine area. By 2014, the center will serve 2,000 students, says SMCC President Jim Ortiz. “It’s evident that institutions of higher education can be a magnet for companies coming in and would need a trained work force,” he says. “It’s a model the rest of the state can follow.”

The center will also be a boon to companies already in Maine. BIW spokesman Jim DeMartini says in an email that “it would enable our current engineering staff to pursue their continuing education and it would also help to create better awareness at the high school level of the importance and value of an engineering degree.”

Renewable energy/ composites

ASSETS:

13 miles of transmission lines

21,000 workers in a 50-mile radius with training that could translate into a green industry

Close to I-295 and the coast

Buildings well-suited for manufacturing and product development

Onsite worker training available

Just this month, MRRA hired Thomas Brubaker, a network energy manager for the VA New England Healthcare System, to oversee the development of the Brunswick Renewable Energy Center, a “living laboratory” where companies could research, develop, manufacture and test prototypes of various energy technologies, says Levesque. The center would also function as a green business park that generates power for itself and potentially for the surrounding community, using cheaper electricity prices to entice businesses to locate there.

BREC would be modeled after the University of California Irvine, which this year received $2 million to expand its sustainable energy research. MRRA has already secured $400,000 from the Maine Technology Institute and the U.S. Economic Development Administration to launch a feasibility study, which will take 18 months to complete.

As renewable energy takes the forefront of business and political initiatives, Levesque and others see a prime opportunity to get in on the game. BNAS has already garnered attention from Norway-based StatoilHydro, which has developed and installed the first full-scale floating offshore wind turbine, and recently toured BNAS and other Maine locations in its quest to expand the project.

Economist Lawton recommends the facility also become its own public utility. “It wouldn’t so much produce it, but rather be a center where the effects on the grid or the potential of different technologies that could serve as alternative sources in Maine could get first level feasibility testing,” he says.

But before Maine and BNAS can be a leader in wind turbine manufacturing, the state will have to prove the industry is big enough, says Jack Parker, CEO of Reed & Reed in Woolwich, a construction company that has of late focused on installing wind turbines in the Northeast. “We have to grow the onshore and offshore market until there’s enough critical mass to attract a large manufacturer,” he says.

The reason? Wind turbine components are heavy and expensive to transport, which means they should be manufactured close to wind farm sites. But BNAS’s geographic location, plus a nearby work force capable of transitioning to making wind turbine components and the state’s favorable regulatory environment for such projects, could help the base attract that manufacturer when the time comes, he says.

New horizons

Other potential reuses for the base include capitalizing on its 250-room hotel and golf course by making it into a conference center, as well as using its advanced IT capabilities to attract back-office data operations. The property has a single mode fiber optic network that is 10 to 30 times faster than other fiber networks in the marketplace, according to MRRA, that could be used to lure companies like athenahealth, which recently opened in Belfast, and Boston Financial, which opened in Rockland, says Renault of the Innovation Center, a partner with MRRA and TechMaine on the project.

“The notion is that Maine could be a great location for low-cost domestic sourcing for big IT companies,” she says, competing with places like Boston, Chicago and Washington, D.C. A two-year, $2 million federal grant to the DECD and the Department of Labor is funding cluster development and training for workers displaced from the base’s closure.

Also in the equation is the Topsham Annex, where a 12.5-acre section known as the Triangle could become an office park or service center, says Topsham Planning Director Rich Roedner. The fate of its 177 housing units is still to be determined (for more on housing, see “The housing wildcard,” this page.)

But before any reuse plans can be realized, town and business officials will be in limbo, waiting for the property to fall under MRRA ownership, a complex process involving numerous federal agencies. One bright spot is that a recent bill passed by Congress will allow MRRA to get the property through a low- or no-cost economic development conveyance, instead of having to pay fair market value. But until MRRA owns the property, enticing companies to locate at the base is a tough sell. “Our biggest challenge is getting the property,” Levesque says.

And even then, building the economic base up to meet BNAS levels is a process officials expect to take at least a decade, if not two. “It’s not going to happen in five years. It’s a 20- to 25-year endeavor,” says Roedner.

Building a new economy in the worst recession in decades may not be ideal, but those involved are optimistic the region can weather the transition and ultimately position itself as a vital statewide economic hub. “People are going to come back in 20 years and look at what’s here and say it’s the best thing that ever happened,” says Roedner. “It will become a thriving area again.”

Back at the base, the remaining P-3 planes have been tucked into the hangar, its thick fabric doors slowly lowering like a window shade. The troops have left the hangar, gotten into their cars and gone home, perhaps to pack before shipping out. Levesque stands outside his office at the base’s entrance, watching the cars trickle out. The traffic used to be so loud he could hear it in his office, but today, it’s just a murmur.

The P-3s may not have left yet, but to Levesque, that era is already over. “What you’re seeing today is past,” he says. “We have to create a new future here — we have no choice. We have to create a new economy, and we’re using this property as the base of the new economy.”

Comments