Portland-based architecture firm changes the approach to medical office buildings

For Ellen Belknap, president of the Portland-based architecture and engineering firm SMRT, all of the Affordable Care Act concepts can be honed down to a few simple concepts: Improve the quality and experience of health care, reduce the per capita cost and increase access for millions of uninsured Americans.

She also acknowledges those objectives are easier said than done. The transformation of health care, she says, requires “not just one solution, but many, many solutions.” Doctors, nurses and other medical professions providing the care are on the front lines, but Belknap says architects can be part of this transformation by helping providers work in spaces supporting primary care that is collaborative and proactive in helping people stay healthy.

“This is not easy. This is a culture change in every respect,” she says. “As architects, one of the real challenges we face is moving the education process forward — building awareness and understanding so that providers see the merits of this new model of health care.”

Belknap, leader of SMRT's health care market sector, says the Portland-based firm is seeing an uptick in the market for medical office buildings in Maine as well. SMRT was the interior architect for Mid Coast Health Services' new primary-care clinics in Topsham (which opened in March) and Bath (slated to open in 2015) and is also designing the new Martin's Point medical office building in Gorham that's slated to open in September. It also designed Martin's Point's $17 million Portland Health Care Center that opened in 2010, featuring a “patient-centered medical home” approach to primary care that emphasizes wellness and patient education.

“As a company, the volume of work generated by health care typically has been 30% to 50% of our overall business,” she says. “Until recently, most of that was at acute care hospitals [notably, as architect of MaineGeneral's new $312 million hospital that opened last fall in Augusta]. There's no doubt a shift has occurred. This year 80% to 90% of our health care work involves outpatient facilities.”

A recent article in Modern Healthcare provides context for Belknap's observations, noting that the health care construction industry is accelerating its efforts to create medical office designs that utilize “lean” efficiency concepts that decrease patient waiting times while also promoting a collaborative approach to “improve quality of care and reduce costs.” Likewise, a nationwide survey of nearly 500 hospital and health system executives, conducted last fall by Health Facilities Management and the American Society for Healthcare Engineering, explicitly identifies the ACA as a catalyst for expanding or building new outpatient facilities that would include services such as blood tests and imaging, traditionally done in hospitals: 22% said they were considering medical office building expansion, up from 16% in 2012, while 18% planned new medical office building construction, up from 15% in 2012.

“Next generation” medical offices

Belknap says she spends a lot of time talking with health care providers, as well as reading medical journals, to gain a deeper understanding of health care trends and best practices. What has emerged from that research, as well as her two decades of experience designing health care facilities, is a detailed, three-page prospectus laying out SMRT's vision for the “next generation” medical office building.

There are four defining characteristics of the new model of health care known as the patient-centered medical home the next generation building designs are designed to support:

• Mindshift: The first, and in some ways most important characteristic, she says, is the “mind shift” that is needed to flip the traditional “provider-centered” primary care model in which doctors wait for sick patients to show up, focus only on the ailment presented due to limited time and then send them out with a prescription or referral to another health provider. In a patient-centered practice, by comparison, doctors collaborate with other care-givers such as medical assistants, nurses and behavioral health specialists. Simple care might be assigned to those non-physician providers on occasions when the doctors need to spend more time treating patients with serious and complex health problems. And the entire care team pays closer attention to preventive care and better management of chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes. Continuous quality improvement is embraced as a guiding principal for the practice.

• Structure: To support those goals, Belknap says, the “structure” of a primary care office needs to change to ensure that it's truly patient-centered, with a doctor-led team providing “continuous, coordinated and comprehensive care.” Electronic medical records must be easily accessible and provide up-to-date information about patients. Adding specialists trained in behavioral or mental health can enhance the care team's ability to help patients identify barriers affecting their ability to stay healthy.

• Catalysts: These are changes that support the patient-centered focus. They include same-day medical appointments and extended hours; electronic health information with 24/7 access; a team-based clinical setting; and connections to additional resources in the outside community.

• Outcomes: The expectation is that if the above three characteristics are present, the desired “outcomes” will fall into place as well — including improved health, satisfied patients, reduced costs and fewer unnecessary emergency room visits and hospital admissions or readmissions.

Designing the space

Although the new patient-centered medical home model for primary care doesn't necessarily require a bricks-and-mortar solution, Belknap acknowledges many traditional medical office settings have limitations that make it difficult to achieve the hoped-for improvements without at least some renovation or redesigning of the space.

Sometimes, the best solution may be to build a new facility, which is what Martin's Point Health Care decided to do instead of renovating a 5,000-square-foot primary care clinic located in rented space within a sprawling 19th Century Gorham farmhouse.

Dick Daigle, vice president of support services at Martin's Point Health Care, says the decision to build a new facility less than a half mile from its location on Main Street in Gorham was driven by the desire to create a truly patient-centered medical office — something he says was not feasible within the historic Old Richardson Place.

“We basically had adapted to what was available,” he says. “It didn't lend itself to the best coordination of overall care. There's a lot of separation, a lot of traveling back and forth among the caregivers.”

With its Gorham practice growing and needing more room, Martin's Point opted instead to build a 12,500-square-foot medical office building at the intersection of routes 25 and 237, described by Daigle as a “gateway to Gorham.” It selected SMRT as architect, PC Construction as builder and Sebago Technics as the site engineer for the $5 million project.

“We are looking at this as strengthening our practice,” he says, noting that the new clinic also will have radiology, mammography and a blood lab services onsite that will allow patients to have those needs be met in addition to traditional primary care. Although the Gorham clinic is not participating in the statewide patient-centered medical home pilot program, Daigle says the new facility is being designed with that primary care model very much in mind.

“Certainly, achieving the 'triple aim' goals is one of our chief areas of focus,” he says. “We want to be on the leading edge of transforming health care.”

Derek Veilleux, leader of SMRT's health care architectural team, says he and Belknap engaged the Martin's Point staff in a very collaborative design process that begin with a “blue sky” visioning session led by SMRT that included exercises designed to identify the clinic's priorities and needs. The preliminary discussions also included non-medical issues that nevertheless were relevant to the new clinic's overall cost — for example, whether Martin's Point would seek LEED certification for the building or pursue a more pragmatic “green for a reason” approach.

“What we want to make sure we do is that any decision that's made is also operationally sound and right for the client,” Veilleux says.

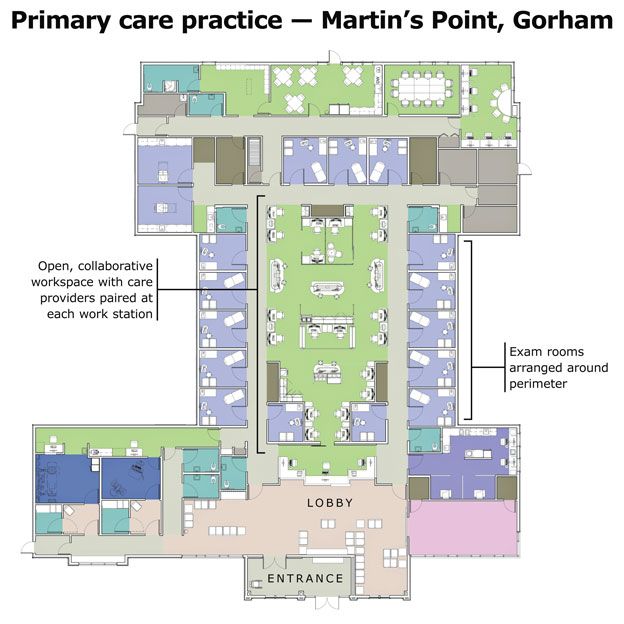

The heart of the design, he says, is a centrally located collaborative team space in which physicians can easily confer with each other and other medical providers, instead of being isolated in private offices. The open central space, with exam rooms arrayed on the sides, is key to the new design and operational model for SMRT's next-generation medical office buildings.

The openness is intended to encourage discussions among the members of the core clinic team about referrals, scheduling and triaging of patient care, in turn reinforcing a collaborative approach among the caregivers.

Veilleux says tablet computers and 3D visualization software facilitated those early planning discussions with Martin's Point's caregivers, helping them see how the different design options might work for the Gorham practice.

“How spaces are designed does matter and can play a major role in clinical outcomes,” Veilleux says. “But the building in and of itself can't solve the problems we're trying to solve in health care. It's a critical piece, but organizationally there's a need to create systems which provide coordinated care that will help people, especially those who are chronically ill, be healthy.”

Veilleux and Belknap say the new medical office building in Gorham, and others they've recently designed for Martin's Point in Portland and Mid Coast Health Services in the Bath-Brunswick region, take advantage of new information technology to create easy access for all caregivers to every patient's electronic medical records. Doing so helps them anticipate and respond to their patients' care needs and frees up space previously taken up by the storage of paper files. Patients also benefit by having “one stop access” to expanded services such as basic blood tests and imaging procedures.

Flexibility and adaptability for the practice are part of the design, too, allowing for easy conversion of the peripheral rooms to accommodate changes in staffing ratios or increased numbers of patients.Veilleux says the planning process for the new Martin's Point clinic in Gorham very much benefitted by having PC Construction, the construction manager, involved in the project from its earliest stages as an additional source of information and feedback.

“In many cases, we discover potential problems before they actually occur,” says Joe Picoraro, project executive for PC Construction. “They are found earlier in the process. That's a huge time-saver, and money-saver. We're also getting an understanding how the owner intends to use the facility and that helps us make suggestions that will improve the quality of the building and ensure it meets the owner's goals.”

“A lot of it gets back to trust,” he says of the collaborative approach taken in both the Gorham project and the Portland project his company partnered with SMRT to complete for Martin's Point in 2010. “We are all separate firms, but in the end we are working together under one flag, and that's Martin's Point.”

Will it work?

Joanne O'Neil Lafferty, quality improvement specialist with Maine Quality Counts, an independent collaborative aiming to improve health care in Maine, says there are roughly 200 primary care practices involved in various “medical home” pilot programs throughout the state. She's co-author of a white paper with SMRT's Belknap, “Patient Centered Medical Home: An evolving approach to primary care medicine,” and recently presented with her a webinar to primary practices statewide.

“There are loads of practices throughout the state trying to transform the way they do their patient care within their existing site,” she says, noting that the starting point for many involves breaking away from the model of a doctor working privately and seeing one patient after another in closed exam rooms.

Many practices are beginning to expand the duties of non-clinical staff beyond merely checking in or checking out patients to include tracking referrals and making sure patients actually follow through on the doctors' recommendations for specialty care or follow-up visits.

“The crux of what we're seeing is that many are moving from provider-based care to team-delivered care,” she says.

The obvious question is whether the patient-centered model of care and the new approach to designing medical office buildings will achieve the “triple aim” goals of improving people's health and their experience of care while also lowering its cost.

A recent progress report of Maine's patient-centered medical home pilot program offers encouraging examples from some of the participating practices. Several participating Martin's Point practices, for example, saw an almost 10% drop in their patients' hospital readmission rates simply by making sure to call them one to two days after they're discharged to review medications and their care plan. Eastern Maine Healthcare System's Community Care Teams has seen a 76% reduction in emergency visits and an 86% reduction in hospital admissions by paying closer attention to the most complex, high risk, high need and/or high cost patients served by its pilot sites. And pilot practices across the state have seen improved adherence to recommended care by diabetes patients across all five care quality measurements, with almost 70% now having blood glucose lower than 8%.

“Maine is ahead of the curve,” Belknap says of the PCMH pilot program. “I think our work is ahead of the curve in terms of being able to explain the model and enhance it so that it actually delivers better results. It's an exciting time in health care — it really is.”

Comments