Maine farmers: Cultivating a profit from organics

Organic farmers will tell you it's all about the soil. But sitting at any farmhouse kitchen table, it's clear that's where organic farming plays out, starting with the inevitable bookkeeping ledger and calculator laid out prominently.

The ledger tells the story of the challenges today's organic farmers face. Certification, transportation, equipment, energy and feed fees chip chunks out of gross revenue. Price fluctuations show up in lower income if there's an oversupply of tomatoes, or an unexpected bounty if an item like organic milk is in high demand and supplies run short. Access to hay fields for grazing can make or break a dairy farmer. And while the local food movement is helping all types of farmers, organic growers still find they need to educate consumers about why their goods cost more and how they differ from local or natural food labels.

“It's not easy to become an organic farmer,” says Ted Quaday, executive director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA), which certifies organic farms for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, among other activities. “It's all about building healthy soil. That's basically what gets certified.”

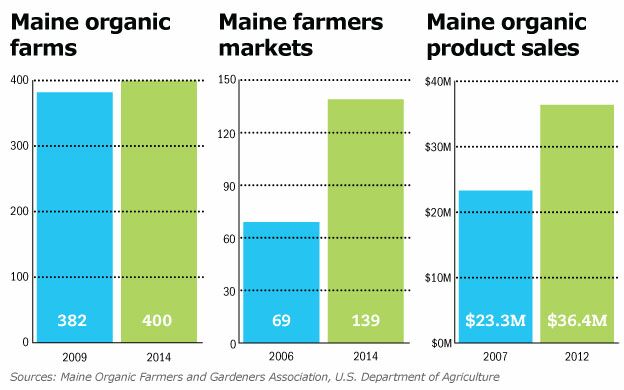

Maine has 400 organic farms, plus another 25 organic processors, Quaday says. That's up from 382 MOFGA certified organic farms in 2009. The number of Maine farmers markets, which are big sales outlets for many organic farmers, doubled in the past eight years to 139 in 2014. Sales of organic products rose to $36.4 million in 2012 from $23.3 million in 2007, according to the USDA's National Agricultural Statistics Service report in July 2014. Even Walmart is riding the organic bandwagon, having last April brought in Wild Oats to relaunch its brand, with the aim of saving customers 25% or more on organic groceries.

And bucking national trends, the USDA report found the number of younger farmers in Maine is increasing, presaging the growth of next-generation farmers. Also notable is the average age of organic farmers is lower than that of conventional farmers.

Dave Colson, MOFGA's agricultural services director and the owner of New Leaf Farm, an organic, mixed vegetable farm in Durham, says the preponderance of new farmers coming to Maine are doing so because of support in the state for locally grown products. “The increase in local food, organic and otherwise, is enormous,” he says. “In the 1980s, when we started, there were only six to eight farmers markets. And restaurants featuring local foods are growing dramatically.”

“But there's still a disconnect about whether local is the same as organic,” says Colson.

Becoming certified organic requires that MOFGA or another USDA-qualified certifying organization check the process of a farm, that is, how it grows its vegetables or feeds its animals. Certification has several steps and often takes three to six months to complete. A farm field can receive organic status if no prohibited materials, like a synthetic fungicides or fertilizers, have been applied for three years. While the USDA has strictly defined the word “organic” and its use on food packaging, there is no similar government guidance or controls for using the terms “local” or “natural.”

Farmers transitioning from conventional to organic need to keep detailed records of everything they apply to the soil. Many fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides and fungicides used by conventional farmers are prohibited in organic production, including fungicides on treated seeds. Animals certified organic must eat organic feeds. MOFGA inspects each farm yearly to assure they comply, and charges a fee each spring based on revenue. The federal government refunds part of the fee in the fall.

That oversight, coupled with thin product margins, has elevated the role of business on the farm. “They work so close to the bone,” says Peter Felsenthal, a Boothbay-based photographer and author of the recently published book, “New Growth: Portraits of Six Maine Organic Farms.” “They have to determine pricing carefully, and they are always looking at their neighbors' pricing. There's an emphasis on bookkeeping.” He notes, for example, that organic egg prices have been stable the last four to five years, but chicken feed prices have risen without a corresponding price increase in eggs to make up the difference.

Through visits to half a dozen farms, Felsenthal noted that none of the farmers are getting rich, but they are committed to doing something good for the earth and their customers. “The association with the customers is very direct,” he says. So, too, is the interaction among farmhands and their appreciation of the land. “They work in gorgeous circumstances. One farmhand told me that the way the sunlight comes through the clouds over the fields is what keeps him going.”

To get a better idea of what it takes to successfully grow organic, we visited three organic farms representing current agricultural trends. Balfour Farm in Pittsfield, a certified organic dairy farm that makes cheese, yogurt and other value-added milk products, is being sold by its current owners, who want to set up a smaller farm on part of the 100 acres they now own because they lack their own grazing fields and their kids don't want to take over the farm. Goranson Farm in Dresden, which in 1996 transitioned into an organic farm, is focusing on ways to improve soil nutrients and diversify its crops in anticipation of the next generation taking over. And Squire Tarbox Farm on Westport Island represents the boom in young farmers and the move to add season-extending crops like bok choy typically not associated with Maine.

Balfour: Farming small

Elbows resting at the edge of her kitchen table, hands wrapped around a large mug of fresh-brewed coffee, Heather Donohue of Balfour Farm leans forward and talks purposefully about how she and husband Doug want to sell 17 acres of the core farm and build a much smaller house, creamery and 10-stall barn on the remaining 83 acres, which is largely wooded, as they downsize. Three Labrador retrievers and two house cats seek attention and a space before the sizable wood stove that Heather fired up moments before.

Heather has just finished showing her visitor through the hoop house, where many of the herd of 40 calves and cows stare outside, unwilling to venture into the pounding snow. Another building houses several pigs and a new litter of piglets along with chickens nuzzling against them for warmth. Alongside the farmhouse in the creamery, where the farm produces butter, yogurt and cheeses, a worker repeatedly kneads and squeezes water from a solid yellowish lump that eventually will turn into butter.

Like many organic farmers, the Donohues have had to change with the times. That includes two years ago deciding to no longer sell milk and focus on value-added products like cheese and yogurt, which bring in more money.

“A couple years ago, the insurance company said it wouldn't cover raw milk anymore,” says Heather, sliding her index finger down the page of her bookkeeping ledger. “We had to sell 100 gallons of milk to pay for insurance for a month.”

They also realized their prices were too low to make a profit. And while they upped the price to $4.50 per half gallon for milk sold at farmers markets, value-added goods brought in more: $18 per pound for hard cheese and $13 per pound for soft cheese.

Raising prices and switching to value-added products made a big difference. “We were in the hole for the first two years here. The last two years were the only time we didn't see a loss on Schedule F [profit or loss from farming on income tax form],” says Heather.

Still, expenses are steep. Their net income was only $36,000 of Balfour's $140,000 in gross sales in 2014, with $104,000 going toward keeping the farm running. Feed and energy are the two biggest costs. Organic grains and soil amendments like nitrogen fertilizer typically cost more than conventional grains and chemical fertilizers. The MOFGA organic certification fee ran $1,350, and they got $900 back from the federal government, which reimburses up to $750 per certified product type, for example milk products and vegetables, both of which Balfour produces and sells.

Balfour is their third farm, though Heather and Doug weren't born into farming. The high school sweethearts set up their first farm on 15 acres in Alton, N.H., where Heather taught middle school science and Doug was a contractor and builder. They initially bought a beef cow and one milk cow, Blackie, now 15 years old and still with them. They enjoyed farming more than their full-time jobs, and in 2004 bought a 200-acre farm in northern New York.

They initially raised pigs and beef cows, but the costs to haul the animals to auction and the price per animal weren't enough for a sustainable lifestyle. Heather took a job in an OB/GYN office, but Doug was laid off from his construction job and took a position with Genex, an artificial insemination company. That's where they got the idea to switch to dairy farming.

Through a local church member, they traded their 20 beef cows for 20 milk cows. In 2006 they transitioned the herd to be organic using 100% organic certified feed for a year, a requirement of the USDA's National Organic Program. The NOP also mandates that cows and certain other animals have free outdoor access at least 120 days a year and not be given drugs, except for vaccines. The NOP oversees MOFGA and other USDA organic certification agencies.

The Donohues grew their herd to 50 cows over the six years they farmed in New York. Because their milk was organic, they received a minimum base price, unlike conventional farmers, who face dramatic market price fluctuations each time they sell their milk.

They returned to New England in 2010 when Heather's father became ill, moving 10 cows and 12 to 15 heifers with them in the dead of winter. Their current farm had been vacant for four years, so they quickly got it certified as organic. They needed the certification before one cow set foot on a field to assure the organic process was uninterrupted. With their certification in hand, Horizon (now part of WhiteWave) continued to honor their previous contract on the new farm, which they named Balfour after the Gaelic word for “of or from the pasture.”

Most of their gross sales, $110,000, come from the seven farmers markets where they sell. Another $30,000 is from wholesale to small grocery stores and cafés.

But along with the hefty costs to farm and high insurance rates, Heather says the cost of buying feed because they don't own enough grazing fields is a big reason for their downsizing.

“Energy costs also are a challenge. Take the cheese vat. We pay for electricity to cool products, then heat them, and then cool them. That's all for one product,” says Doug.

Even though they're selling the current farm, neither Donohue wants to get out of farming. “We didn't think we'd been doing this, but we're glad,” says Heather of organic dairy farming. “Being on the go for so long has really worn us down. Our kids are gone and don't want to be farmers. But I'd never go back to being a teacher. I'd rather be outside.”

Goranson: Mining nutrients

Soil health is at the center of organic farming at Goranson Farm, note owners Jan Goranson and her husband Rob Johanson. The farm is known for its potatoes and maple syrup, but produces 60 different crops and grows chickens, pigs and dairy and beef cows. Of the farm's 160 acres, 36 acres are tillable and 20 acres are hay land.

Johanson is quick to point to a USDA study saying the nutritional content of U.S. food has decreased an average of 40% since World War II. “It's because of the way it's grown, the poor quality of produce and the processing that destroys nutrients,” he says.

Johanson spends a good amount of time attending soil workshops across the country, reading farm magazines and figuring out the best way to add soil nutrients. From the early 1960s through mid-1980s, when Goranson's father ran a conventional potato farm, the soil wasn't rotated well and had no earthworms, but had plenty of bugs and weeds, he says.

“It was hard to figure out how to transition to an organic farm. We reduced the chemical inputs and farmed transitional organic for three years,” says Goranson. That means using organic practices on a field that still has hundreds of chemical residues from conventional weed killers, fertilizers and other soil additives.

“Most industrial chemicals break down after three years,” says Johanson. “We've been organic now for 16 years. The earthworms are back and the soil health has evolved.”

He adds, “Soil is a living piece of the farming we're doing. We feed the soil through crop rotation to grow healthy food that is higher in nutrition.”

Thumbing through a recent soil conference agenda laying on the kitchen table, next to the calculator and ledger, he rattles of a list of necessities for good soil biology: nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, pH and cation exchange capacity. It's more challenging for organic farmers to get and keep soil healthy, because they cannot use conventional chemical enhancements.

Goranson, most of her long hair tucked into a woolen hat and wearing three layers of clothing to keep warm, walks her visitor through a storage area in the barn where workers busily box squash and other vegetables, left over from the fall, for the Saturday farmers market. In the adjoining greenhouse, another worker plants onion seeds.

“Life was easier with systematic fungicides. There were huge benefits to using a chemical regime,” Goranson says of her father's farm. He grew potatoes on 80 acres and didn't think her plan to grow organic food was realistic. Goranson had worked in California for an executive search firm after college before returning to the farm when her father was diagnosed with cancer.

“We scaled way back when we started farming organic,” adds Johanson, who gave up his own farm to join Goranson when they got married. “We have six acres of potatoes, down from the 14 acres when we made the transition to organic in 1996.”

One of the reasons organic farmers tend to have smaller fields is they need to use crop rotation to assure healthy soil for the next season. “Rotation land takes up crop land,” says Johanson. “Half of the farm is out of production in any given year.” Each time the farm sells vegetables, it is selling off the minerals they take from the soil, which will need to be replenished the following year by cover crops and green manures, he says.

Johanson is considering growing crops with long tap roots, like alfalfa and daikon radishes, which can bring up minerals deeper in the soil that are not normally available to other crops.

“When you own your own business, you really need to keep educating yourselves,” adds Goranson.

One challenge to farmers like Goranson and Johanson is paperwork. Goranson Farm took in gross sales of $535,000 last year and netted $37,000. The farm bought a large piece of machinery and a truck to take goods to farmers' markets. One of Maine's larger organic farms, it employs 15 full- and part-time people at the height of the summer growing season. One-third of gross sales are wholesale to the Portland Food Co-op, Rosemont Market and Bakery and Whole Foods, with the rest through farmers markets, community supported agriculture programs and retail farm stands.

The farm pays $1,800 for MOFGA organic certification. Johanson says it's a good value, but it also comes with a lot of paperwork. “We have to create a 50-page document every year that lists everything we grow and the number of row feet planted of each particular crop,” he says, adding that he spends too much time doing paperwork rather than working the fields.

Both he and Goranson see the certified organic tag as valuable. “Clarity is a big thing in terms of the people who say they grow organic but aren't certified. Certified organic is a valuable tool. Why not be clear?” Goranson says.

With their diversified products, Goranson says everything on the farm is optimized, and it is run like a business. “We really do enjoy farming,” she adds, “But I'd like not to have to work six days a week in the winter.”

She says their two sons are interested in returning to the farm, so they want to make it as productive as possible. Her recommendation to farm couples: one person should have another income to bring other money into the farm.

“Most successes come when both farmers have part-time jobs,” she adds. “We've been farming for 30 years. I don't take anything for granted. It's quiet work, but physically demanding and hot.”

Looking distantly out the window, past the silhouette of a farm cat, her eyes twinkle when she adds, “You find beauty where you are. You can look out across the fields or look at a head of lettuce.”

Squire Tarbox: Creative upstart

For newer farmers especially, every penny counts, and the certification fees and paperwork can be daunting.

“My wife and I live meagerly,” says Kyle DePietro, who also has two small children. He leases Squire Tarbox Farm, off the Lower Hell Gate portion of the Sasanoa River, and has about six acres of tillable land, half of which he cultivates. The other half is for rotating cover crops.

DePietro, who is scraping dead bees from last year's hives when his visitor arrives, walks across a board over a small stream and toward a hoop house — which despite being unheated protects some vegetables to extend the growing season.

He started the farm after his parents in 2003 bought the Squire Tarbox Inn, where his father is a chef, and where he initially tended the inn's gardens.

His primary source of sales is farmers markets, from which he grossed $100,000 last year, up to 80% of which goes back into the farm. Among his crops are fingerling potatoes, heirloom tomatoes, peppers, salad greens, kale, chard, carrots and beats.

“I also try to find new, interesting items to grow, like Mexican sour gherkins, also called mouse melons. It's a unique crop, but it's not the most lucrative,” he says. He also grows bok choy and tatsoi, which are Chinese crops.

For a new organic farmer like DePietro, startup costs were huge. He got a line of credit from Bangor Savings and then from MOFGA to invest $7,000 in a box truck for the farmers markets, $30,000 for a tractor, $7,000 for the hoop house, $2,000 for several smaller hoop houses and another $15,000 each spring for soil amendments, compost, seed-starting mix, market fees and MOFGA certification.

“We built from scratch,” says DePietro. “The infrastructure costs were huge.”

For a small, startup farmer, even $1,000 for MOFGA certification is steep, especially since that payment comes during the expensive spring outlays and the $750 USDA reimbursement doesn't come until the fall.

Still, he says the MOFGA cost and paperwork are worth it. “The paperwork is becoming easier. Staying certified says we do care and we want the public to know we care.”

Being on a tight budget has stimulated DePietro's creativity. For instance, instead of plunking down $1,000 for a lettuce spinner, he repurposed an old washing machine drum that was free.

Still, he advises new farmers, “Don't be afraid to borrow money to do things right.”

His longer term dream, as his farm is near the water's edge, is to add oyster aquaculture and seaweed as animal feed or food for people.

“It's very challenging to have the right infrastructure to do business as a farmer. Efficiency is everything,” he says. “On a small farm with different products, you need to keep a keen eye on how the process works. Small things can change output. And beyond growing products, you need to be a builder, mechanic, innovator and spokesman for the farm.”

The spokesman role is one he especially enjoys at farmers' markets, suggesting recipes and telling customers how to use items, especially the more unusual produce.

“Sometimes that's what makes the sale,” he says. “A carrot is just a carrot until you put a face behind it and a story.”

Read more

Comments