New collaborations, incubators aim to breathe life into Maine's biosciences

A group of three bioscience-focused nonprofits say they plan, through mutual cooperation and by housing very early-stage companies and researchers, to boost the state's biotechnology business acumen and national status.

The new life sciences collaborative, known as the Life Sciences Group, or LSG, was started by the MDI Biological Laboratory in Salisbury Cove, Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in East Boothbay and the Foundation for Blood Research in Scarborough. The plan is to open the LSG to other bioscience labs and companies. For example, Kennebec River Biosciences, a commercial aquatic animal health and testing services company in Richmond, is now the fourth member of LSG.

The group says it hopes to help attract outside investment and entrepreneurial thinkers to Maine. In its mission statement, LSG notes it wants “to improve the well-being and economic welfare of Maine's citizens through the modernization and expansion of the state's science and technology economy.” The statement adds that the LSG's loose alliance of diverse and small Maine life sciences R&D organizations brings to the state an interactive and complementary network of physical, scientific, clinical, business and mentoring resources, along with workforce training programs and a novel distributed life sciences business incubator called the LSG Biotech Collaborative.

Each nonprofit already is incubating startups and independent researchers under its roof. Those potentially could turn into future partnerships for themselves or with other LSG members and startups. For example, the Foundation for Blood Research, a nonprofit that offers blood testing services, is incubating three startups, says FBR's President and CEO Jane Sheehan.

She says the first planned LSG activity is a get-together in late spring at Bigelow so scientists can connect and build relationships.

“The three institutions want to convert science to more of a commercial purpose, keep it in the state and work together as a catalyst for economic growth,” she says.

The idea for LSG hatched in the late fall of 2013 over what Bigelow's Executive Director Graham Shimmield calls an excellent bottle of wine in the living room of MDIBL's President Kevin Strange. Neither can remember the type of wine. FBR's Sheehan, the third leg of the stool, knew the founders of Bigelow, and Shimmield and Strange knew each other well, so the partnership flowed easily.

“We wanted a double thrust, to have the incubation ability to engage more closely with smaller companies and have synergies, and to create a presence in Augusta, which we have not penetrated,” Shimmield says. “We want to create an awareness, but we're not a lobbying group.”

New science and tech plan

LSG's momentum is timely, considering that the Legislature this month will review the revised state Science and Technology Plan, which is updated every five years. Sheehan, in particular, has made efforts to improve the plan, which she says will be easier for legislators to read. It will include 11 major points and at 15 pages, be about half the length of the 2010 plan.

Shimmield says the prior plan didn't include specifics about how to build up R&D investment or how to measure progress. The new plan will. He adds that the new plan builds on efforts by states like Kentucky that have seen better results. “In the current plan, we're trying to talk about where the impacts will be,” he says.

He'd like to see industry and academia work together better. That's especially important in light of academic budget constraints, he notes. Among other issues, belt-tightening caused the University of Maine System's board of trustees last October to cut the University of Southern Maine's graduate Applied Medical Sciences program.

Shimmield adds that it's important to form partnerships and strategies that “move along on a plan that isn't chopped and changed one year to the next.”

He says that while organizations like the Maine Technology Institute play an important role in stewarding technology, large organizations like Bigelow go to MTI for a specific project. “What it doesn't do is to create a self-perpetuating network,” he says. “LSG wants to be more collaborative than that, and to be on a more generic mission of the economy.”

More accountability

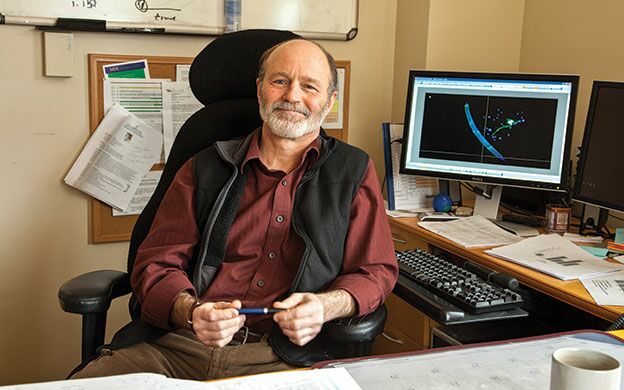

MDIBL's Strange says he pushed for the LSG because of the lack of a real strategic plan at the legislative level and no long-range investment strategy. “You can't throw a little bit of money here and there,” he says, pointing to the focused, 30-year commitment and build-up of the now-successful Research Triangle Park biotech cluster in North Carolina.

“They're now doing that in other parts of that state,” he says. “The investment has real milestones and accountability. There's a real need for accountability and standards in [Maine's] state bond funding,” he adds, saying he was involved in the bond discussions last year. “You should hold Maine to milestones.”

After being asked to talk before the Legislature several times and then to draft an accountability and milestone strategy, he says, “One thing that became clear to me, for profit and nonprofit R&D organizations, is they're not part of the conversation. We need to work together. That's one of the main driving forces behind LSG, the long-range visions and strategies and putting into place long-range accountability and standards.”

“Maybe I'm tilting at windmills, but I think Maine has a lot of potential,” Strange says. “It's next to Boston and has excellent R&D, but it's spread out all over the state. We have a trained workforce, but no work for them. We need a long-range plan with teeth.”

There's no shortage of blame for Maine's shortfalls. He points to the Legislature, MTI, academics and research organizations as all being part of the problem, and all part of the solution. “We live paycheck to paycheck,” he says of his lab. “If the state doesn't do well, we don't do well.”

Strange adds that he's tired of ivory tower academic centers measuring output instead of outcomes. Currently, most researchers' work doesn't lead to science that can be commercialized. “The average academic doesn't start companies,” he says. “They publish papers. Most discovery doesn't lead to commercialization.”

Internal growth

With LSG, incubating businesses within the walls of research and other organizations aims to pump up those commercialization numbers.

With its incubator, FBR is looking to grow. “Part of the incubator's creation is to build collaborations in the building with other scientists. It's a new source of income for us, too,” she says. She declines to give square-foot rental costs, saying only they're about half of similar space elsewhere. About 5,900 square feet in the building and adjacent areas could house up to eight startups, and those companies could potentially employ a total of 40 people, she notes.

Chemonex LLC leases about 700 square feet at FBR for its two employees, founder and entrepreneur Vladimir Koulchin and his wife, who are developing diagnostic kits and immunobiology agents. Trebor Lawton, another serial entrepreneur in the incubator, is working on faster tests for two different lung fungal diseases at his new company, Niche Diagnostics LLC. He's leasing about 600 square feet and says he's eager to interact with other startups in the facility. Sheehan describes the third occupant, who prefers to remain anonymous, as a long-time biotech entrepreneur also working on medical diagnostics.

Since FBR analyzes blood tests for diseases, and the incubator startups so far are developing the actual test products, the synergy could work well in terms of sharing knowledge from test results to devise better tests, several members of the incubator say. There's also potential for the startups to access future customers.

Another person involved with the FBR incubator effort is William Palin, FBR's trustee and scientific director, who serves as an unpaid consultant. He was a principal scientist at diagnostics company Alere in Scarborough and vice president of research at rapid diagnostics company Binax Inc. in Portland. He's also recently developed a rapid and less dangerous test for arsenic in water, Palin explains. Most current tests contain mercury in the bottle tops, which must be disposed of in a special manner, she says.

MDIBL now houses two companies. One is Novo Biosciences Inc., the first MDIBL spinoff company in the lab's 117-year history, co-founded two years ago by Strange and MDIBL researcher and Assistant Professor Voot Yin. Novo is developing a therapeutic compound to help speed tissue healing and stimulate the regeneration of lost or damaged body parts in animals, with the aim of eventually translating it for use in humans.

In January, RockStep Solutions Inc., an information management software company formed by ex-Jackson Laboratory researchers, moved into MDIBL. “The MDIBL is a perfect start-up environment for RockStep,” Chuck Donnelly, the company's CEO, said in a statement when he announced the move. “The institution offers a world-class research environment combined with an entrepreneurial spirit, and we'll have the added benefit of being able to interact with the MDIBL's scientific staff and their extended network of scientific, clinical and business collaborators.”

Bigelow also has a visiting scientist and former executive at Massachusetts drug company Repligen Corp. renting space. Dan Witt, who has yet to establish a company, is conducting early investigation work on rockweed enzymes that he hopes one day may be applied in biomedicine. He brought with him a specialized scientific instrument he owns called a spectrofluorometer and is sharing it with a young Bigelow researcher, so he calls the incubator arrangement a “two-way street” in terms of sharing knowledge and space. If his research pans out, he says he plans to start a company and seek funding to move it toward commercialization.

Read more

MDI lab partners with Australian research group

MDI Bio Lab researcher IDs two drug candidates for chemo side-effect

Comments