Can hop-growers, maltsters and brewers make a truly Maine beer?

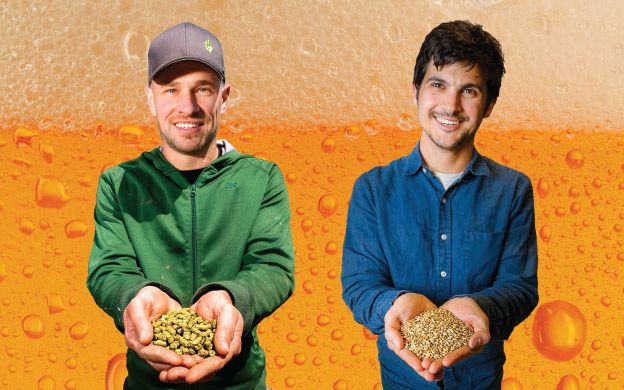

Maine is where the grain is, says Joel Alex, founder and maltster of Blue Ox Malthouse in Lisbon Falls. Add that to the sprouting number of hop growers in the state and you've got a formula for sourcing two of the main ingredients in beer locally.

And that's just what local craft brewers and some government officials want: a truly Maine beer, with Maine-grown and processed ingredients. The side benefits are higher prices for farmers producing malt-grade barley and varieties of hops as well as a stable, local market for those products. That completes the chain from farm-to-table for beer: from field to processor to craft brewer to consumer.

Craft brewers already are taking the leap to buy local. Rising Tide Brewing Co. of Portland said recently that it plans to use some Maine-grown and processed grains in every batch of beer it brews. It will source malted barley from the Maine Malt House in Mapleton and unmalted wheat and oats from Maine Grains in Skowhegan. Rising Tide expects to use at least five tons of malted barley and about three quarters of a ton of unmalted grains grown and processed in Maine in 2016. The company said that when more high quality local options become available, it will continue to evaluate and expand its use of local ingredients.

Rising Tide isn't the only craft brewer hopping onto the trend. Allagash Brewing Co., also in Portland, started shipping Sixteen Counties, a Belgian strong golden beer, on April 16. It is made entirely from malt from Maine with a combination of Maine Malt House 2-row malted barley and Blue Ox Malthouse 2-row malted barley, plus raw wheat from Maine Grains and oats from Aurora Mills & Farm in Linneus.

The two Maine malt houses and 15 to 20 hop growers have a ready market in the state's 70 breweries. That's double the number of breweries three years ago, Dick Cantwell, co-founder of Elysian Brewing Co. and now quality ambassador at the Boulder, Colo.-based Brewers Association, said at April's New England Craft Brew Summit in Portland. In its most recent annual report on the industry, the association estimated the economic impact of Maine's breweries to be $432 million, based on 52 breweries.

Buying from local growers and processors helps craft beer and other beverage makers compete with distinctive flavors and local lineages to ride the “source locally” trend.

To support these efforts, Sean Sullivan, executive director of the Maine Brewers' Guild, said the guild is working with the office of U.S. Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-Maine, to convene a roundtable discussion “in an effort to identify opportunities to accelerate the positive impacts the craft beer industry may have on Maine's agricultural sector.”

Sullivan said the roundtable will be held in Maine likely in the next three to six months. It will include maltsters, hop growers and others in the industry, those who are considering getting into some aspect of the craft beer industry and people who have technology or tools that can be applied to craft brewing.

“If you have 20 beers to choose from and you support farm-to-table, the local aspect will be strong. This is true in Maine, especially in Portland,” says Heather Muzzy, a quality control specialist at Allagash.

Can local hops replace imports?

Historically, Maine was a big grower of hops, says Ryan Houghton, founder and president of The Hop Yard in Gorham, one of the largest hop growers in the state. He's now growing 10 acres, with eight in Gorham and two in Fort Fairfield, and hopes to expand that to 200 acres in five years.

“I want Maine to have 500 acres of hops and I want to make sure it's grown right,” says Houghton, who is growing eight hop varieties. He also consults with existing and would-be hop growers.

The state's 15 to 20 growers harvest about 20 to 30 acres combined, says Andrew Plant, associate extension professor at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension in Presque Isle.

“We'd probably need 250 acres worth of hops to service the 70 craft breweries,” he adds. “So we're now at about 10% of that.” The brewers now import hops from the western United States and elsewhere, partially out of need and partially to get different flavors for their beers.

That growth is nowhere near Maine's production in the late 1800s, before being nearly wiped out by a blight of downy mildew and Prohibition.

“The past year (1876) there were raised (as nearly as can be estimated) about 400,000 pounds of hops in the state, or about 2,200 bales; which at 20 cents per pound would amount to $100,000,” Thomas Reynolds of Canton, Oxford County, wrote in the Maine Department of Agriculture's 1877 annual report section on hop culture.

“The cultivation of hops in Maine is principally confined to the western part of the state ... most extensively in Oxford County,” he continued. “From the best authority, I feel confident in making the statement that Maine hops …will keep longer and retain their aroma fresh and unimpaired to a greater degree than the hops grown in any other section of our country. This being true, it gives greater importance to Maine as a hop producing region than it would otherwise possess.”

Also in 1876, some 42,896 bales of hops were shipped from the United States to Europe. That left about 77,000 to 97,000 bales for U.S. brewers, according to the state's agricultural department's annual report.

Today, the top three producing states are Washington with 28,858 acres harvested in 2014, Oregon with 5,410 acres and Idaho with 3,743 acres, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture and Hop Growers of America statistics. The United States is the top hop producer in the world with 45,238 total acres produced, followed by Germany with 44,102 acres.

One of the challenges Maine and other hop growers face, says UMaine's Plant, is the cost of entry.

“It costs about $10,000 to $20,000 per acre to get started,” he says. “It's such an expensive endeavor to get into with the trellising and capital investment.”

On top of that, it's a labor-intensive flowering crop, and susceptible to downy mildew, which, if not caught in time and treated with chemicals, can ruin an entire harvest. Houghton says he regularly checks his hop plants, which grow on 18-foot poles and wires. When the shoots reach the top of the poles, they stop growing vertically and start filling in horizontally.

All the hop shoots need to be cut down to the ground in the spring to produce better sprouts. The hop flowers need a lot of water and nitrogen to grow, Houghton says. It takes about 125 days for the hop cones to fully ripen, and they're typically cut by hand all at the same time.

Houghton says The Hop Yard is self-funded, plus it received a $40,000 loan from the Finance Authority of Maine to buy a picker — known as a “Hopfenpflückmaschine” in Germany, where his picker was made — and a $25,000 grant from the Maine Technology Institute that it matched with $25,000 to buy a dryer. When the farm expands, it may seek angel or other financing, Houghton says. Founded in 2010, it turned a profit last year.

Currently, The Hop Yard sells some fresh or “wet” hops once a year to local brewers for special seasonal blends, but the bigger business going forward is dry, frozen hops that could be shipped. Those could make up 80% of The Hop Yard's business going forward, Houghton says. Local customers include Rising Tide, Sebago Brewing Co. and Allagash.

Houghton says he hopes to create a meaningful hop industry in Maine.

“Right now, Maine is using a ton of hops and that's only going to go up,” he says. “We know it can work here because the climate is right. It could be a big industry here and it allows farmers to diversify.”

Maltsters need to double or triple production

Farmers also stand to make more money in producing malt-grade barley, says Alex of Blue Ox Malthouse. He estimates that without a middleman, farmers can get 30% to 50% more per grain than what they would otherwise get.

Currently, most malt, which is made primarily from barley but can use other grains like wheat, is imported. UMaine's Plant estimates that Maine's brewers import 30 million pounds of malt made from barley each year for the approximately 300,000 barrels of craft beer they collectively produce each year.

“If Maine farmers were to fully supply all of the barley for malt being used in the state, they would need to produce 7,500 to 10,000 acres of malt-grade barley,” Plant says. That's double to triple the estimated 2,000 to 5,000 acres grown now.

Maine is the largest barley-producing state in the Northeast, and is a large producer of small grains like wheat, rye and oats that also are used to make malt, but much of those grains are exported for animal feed, which gets a lower price, Alex says. Besides water, malt and hops are the key ingredients in beer.

Like the hop flower, growing malt-grade barley — which requires up to 100% of the grains to sprout — can be difficult due to that high-quality specification, the growing season and disease pressure, Plant says.

And the investment is high: Alex says he's already pumped nearly $1 million into his malt house, which uses the traditional floor-germination process of laying the barley in water on the floor and letting it sprout, while raking it routinely to remove excess carbon dioxide and heat.

Jacob Buck, marketing manager at the Maine Malt House, says farmers still need to be convinced to switch to growing the finicky malt-grade barley. “But it will be appealing to farmers if they realize they can make money off of the grain.” He says market demand for the high-quality barley in Maine is still in its early stages, but he's selling to 16 or 17 local brewers who are regularly using his malt, which comes from the 200 acres of barley he grows for Maine Malt House. He says he also sells some barley to Blue Ox Malthouse.

So far, local malts and hops come at premium prices, say Houghton and Alex, but brewers have been willing to pony up because of the “buy local” trend and the desire to have different flavors.

Says Plant, “It would be a win-win if local Maine farmers could grow local barley for local Maine malt for local Maine beer.”

Read more

South Portland’s Foulmouthed brewpub sets late June opening

Brewers, Pingree roundtable aims to expand craft beer impact

Blank Canvas Brewery trades one-way for two-way in move

Maine Beer Co. plots major expansion in Freeport

Allagash Brewing gets some props in Windy City

Windham publisher plans a stand-alone Maine Brew Guide

Craft beer and more to be featured at Skowhegan festival

Crack open a cold one with Maine Beer Co. to honor North Woods

Allagash Brewing named 'Brewer Partner of the Year'

#MBNext16: As craft brewing evolves, Sean Sullivan aims to keep Maine at its forefront

Allagash's Hibernal Fluxus has the winter months, philanthropy in mind

Comments