MDI Bio Lab inspires art for a visceral experience of science

Early one recent Saturday morning on Mount Desert Island, a young scientist eating breakfast at a long, picnic-style table talks about how Fargo, N.D., where she lives, is nothing like the movie, which in reality was filmed in Minnesota.

“Except there is a large statue of Paul Bunyan,” she says. But talk at the breakfast table at the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor quickly turns from pop culture to science, which was the main course at this special two-week seminar on aging for 17 visiting postdoctoral students and 20 faculty that ended July 2.

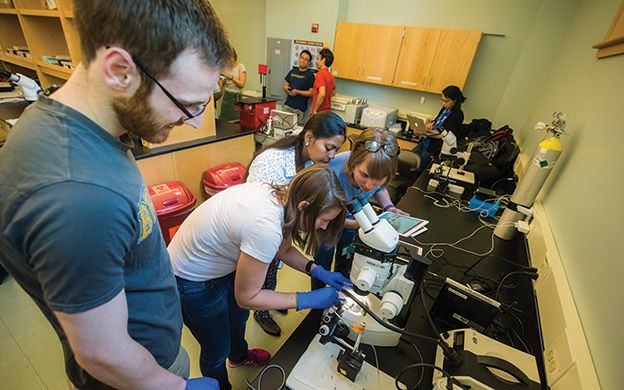

They are here at MDIBL to learn about the breadth of model organisms, including C. elegans roundworms, fruit flies, zebrafish, mice and African killifish that are used to study aging and disease. It is one of the few labs in the world that studies multiple model organisms, giving the students a rare insight into conducting research in other animals.

The table is set up to encourage mingling and sharing of research and ideas. Soon the young scientist is talking about the organism she studies in her home lab: wild birds. She alters their eggs to study the results, which some day may be applicable to human conditions.

“How do you get at the embryo?” asks another young scientist who overhears the conversation and joins the table.

“I drill a small hole and go in with a needle, then find the embryo, you know the white spot in the yoke, and inject it,” the researcher says of the materials she puts into the embryo to alter it.

The other young scientist nods and looks impressed by the technique.

The group of visiting scientists soon heads off to hear a lecture on fruit flies by Vicki Losick, an assistant professor at MDIBL who studies regenerative biology and medicine in fruit flies.

Lifelong pursuit

For Losick, the fruit fly is an ideal organism for studying both wound-healing and aging. Fruit flies have a short lifespan, up to two months, so studying genetic and other alterations is fast. Plus a lot is known about fruit flies, which have been studied for more than 100 years to answer basic questions in biology.

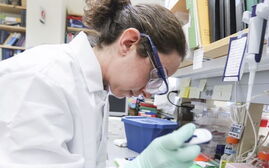

Losick, who joined the lab in February, is studying wound healing, specifically stimulating large cells to grow even larger to heal damaged tissues. Typically, cells divide to heal wounds, so her approach is a new one for wound-healing.

In her lab the day before her lecture, she shows me four types of mutated fruit flies under a microscope that have been lulled to sleep by gas. They were taken from a refrigerator-like locker that keeps live fruit flies at a constant temperature and 60% humidity. Maine, with an average 30% humidity, is inhospitable to the fruit flies, she says.

Like most scientists, Losick is focused on a narrow area that will define her entire career.

“First we need to understand the process to heal wounds,” she says. “Once we see how that happens and how advantageous it is, we can manipulate it.”

The idea is to show that the molecular mechanism for healing for fruit flies also is conserved in mammals, and then potentially look for drugs that can target cell growth. And that can take as long as a career.

“I hope to see clinical applications to my work in my lifetime,” she says.

Art meets science

In the halls leading to Losick's lab and throughout the corridors of the main laboratory building at MDIBL hang photographs, paintings and other art work by artists inspired by science.

Montreal artist and biologist François-Joseph Lapointe makes what he calls microbiome selfies, self-portraits created from the bacteria living in and on his body. Donald Rainville of Camden uses leafs, twigs and house paint to create images of nature that require using all of one's senses to appreciate. And JT Bullitt of Milbridge draws what he imagines are the invisible scientific forces that underlie accidental events, like a coffee ring.

While Mount Desert Island is now home to MDIBL, The Jackson Laboratory and College of the Atlantic, in the mid-1800s it was a haven for the wealthy to summer and for artists to draw and paint nature. In 1901, private citizen George Dorr, who also was interested in science, felt Bar Harbor was being overdeveloped and formed a corporation to preserve land. The land became Acadia National Park in 1929. John D. Rockefeller Jr. endowed the park and much of its land area.

The MDIBL exhibit, which runs through Sept. 30, honors the park's centennial. It includes artist and scientist collaborations , such as among artist Robyn Ellenbogen and MDIBL President Kevin Strange and Assistant Professor Dustin Updike. The work from their collaboration is inspired by C. elegans, a one-millimeter-long roundworm that is one of Strange's favorite organisms to study.

“We're teaching the students how to use a model system,” Strange says. “C. elegans techniques are different than those for a killifish. We need them to ask 'what's the best model system to use?'”

Aric Rogers, assistant professor of regenerative biology at the lab and organizer of the aging course, adds that the young scientists competed to get into the course. “About half are new to the field of aging,” he says. “The other part of the course is early-stage investigators already studying aging and who want to know about other model systems.” A number of the students, he adds, are looking for their next research position, and had the chance to make contacts with visiting instructors at the course.

Funding remains a challenge

Strange says he appreciates the history of art and science on MDIBL's campus. Other labs in the area also link science to music, such as a recent sponsored tweet of Jackson Lab President and CEO Edison Liu rapping in binary zeros and ones. Liu is an accomplished classical and jazz pianist who has performed in public to link science with the arts. Both labs show the integration of artistic and scientific pursuits.

Strange is focused on getting money for the lab's research in the regeneration of body tissues and eventually body parts, and for the related field of aging.

“I could spend my whole day just preparing grants,” he says of the difficult environment for getting funding from the federal government and other sources such as nonprofit organizations focused on specific diseases.

That includes funding for Novo Biosciences Inc., the first spinoff in MDIBL's 118-year history, which focuses on tissue regeneration. Strange and Voot Yin, an assistant professor at the lab, started the company in 2013. Strange says he has to keep the two separate as he seeks financial support for each of them.

“Maine is at a huge disadvantage,” says Strange of luring Boston investors to the state.

One bright spot, he says, is that even during the recent horrible economic times, the National Institutes of Health got a big boost in its budget last year, and he expects the same will happen this year.

New training lab

Another positive is a 6,720-square-foot, two-story training lab in the works on campus that can accommodate more students for IDeA (Institutional Development Awards) Network of Biomedical Research Excellence, or INBRE, courses. INBRE is a federal training program that in Maine involves three research institutions and 10 colleges and universities.

IDeA is aimed at building Maine's research capacity. The funding totals $118 million since 2001, with another $89 million secured as a result of research funded by the program. More than 205 new jobs were created in Maine from the program.

Another key program for the lab is the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence, a $13 million federal grant for regenerative biology and medicine research that is up for renewal in 2018. Strange says the lab must show progress since it received the grant in September 2013 to get a renewal.

Training, including the recent two-week aging and model organism course for visiting postdoctoral students, is a key part of the lab's work.

A $500M bet; cleaning up body garbage

At the end of long days of seminars, the visiting scientists and the public are treated to two visiting lecturers.

Steve Austad, a University of Alabama at Birmingham researcher, made a case for his belief that the first person who could live to age 150 was already born by 2000. And he has a lot on the line. In 2000, he made a $150 bet with S. Jay Olshansky of the University of Chicago, who thinks Austad is wrong.

The payoff for the combined $300, which is in an investment account until 2150, is an estimated $500 million at historical market growth rates over the 150-year period, according to Austad. The downside: neither scientist will likely be alive to collect the money, which will go to one of their descendants or to a designated university.

The one caveat is that the 150-year-old person has to be cognitively intact and able to hold a competent conversation.

Austad asks the audience of scientists and local residents how many of them would take a pill that would allow them to live till 150. Only half raise their hands.

Austad says that's because many worry about their quality of life and cognitive function at that age.

But Austad's message is broader than a mere bet. “Aging kills and debilitates far more people than any other cause because it underlies all of them,” he says. “There's no reason to think we can't go after all these diseases [at once].”

The final night's lecture, by researcher Richard Morimoto of Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., focuses on quality control mechanisms in our cells. Poor quality control, he says, leads to the buildup of body junk in our cells, and that in turn contributes to disease and aging.

“Most components in our tissues and in our brain are constantly replaced,” he says. “So why do we age? Our body goes to the junkyard with molecular clutter. We're exceeding the warranties on our parts.”

That clutter contributes to memory loss and other diseases as we age. He believes one answer lies in treatments that can rejuvenate and regenerate body parts to improve them.

The scientists adjoin for reception to further discuss their work and research surrounding aging.

I decide to enjoy the other benefits of the seaside campus, and walk past the new training lab to a well-known Maine landmark, the Star Point rock formation, which at one time was used by seaman to navigate. I sit on a bench overlooking the ocean at Salisbury Cove and watch as a kayaker with a fishing pole plods toward the dock below. I wonder if he was pondering the big questions of science as he paddles. It's a perfect place for it.

Read more

MDI Bio Lab scientists score patent for heart repair medicine

UMaine one of 37 nationwide STEM projects to get NSF grant

How early childhood stress could lead to costly adult illnesses

Comments