Construction business is booming, but where are the workers?

Photo / Tim Greenway

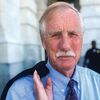

Mark Adams, president and CEO of Sebago Technics, at the construction site of the future home of Patriot Insurance in Yarmouth.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Mark Adams, president and CEO of Sebago Technics, at the construction site of the future home of Patriot Insurance in Yarmouth.

In 2004, Scott Tompkins wrote a Mainebiz column about the need to rehab the public's perception of construction work. In a survey of job desirability that had been recently published, construction had ranked 247 out of 250, just above oil-rig roustabouts.

“I don't know what kind of progress we've made since then,” says Tompkins, director of business development for PC Construction Co. in Portland. “People have a very antiquated view of construction.”

While some trades require strength and work in all kinds of weather, “often you're sitting in a climate-controlled cab with a joystick like you would use in a computer game, with GPS equipment. Those jobs can pay $20 to $30 an hour or more.”

He is among many who says that giving that image a makeover is still necessary in order to take advantage of the hot climate for new construction.

From Bar Harbor to Kennebunk, contractors say that new projects are bigger and more bountiful than they have been since the 2008 downturn.

With relatively low interest rates, companies and institutions that are thriving — like The Jackson Lab, Colby College, ImmuCell Corp. and Tyler Technologies — have major expansions in the works. Maine's hospitals and senior living facilities are rapidly growing to serve the aging population. A slew of new housing projects are under construction in Portland. Municipalities are being forced to replace aging schools, prisons, roads and utilities that are often in dire need of repair.

Construction leaders worry about the impact of perennial labor shortages.

“I'm concerned that if this momentum continues and work continues to be there that [the labor shortage] will impact our ability to meet our clients' needs and schedules,” says Mark Adams, president and CEO of South Portland-based Sebago Technics, which does survey and site work. “We've had one of our most productive years ever. Employees put in hard work meeting client needs with many extra hours. But there's a potential cost to that. You can only expect that for so long before people become overwhelmed and less productive.”

Kevin French, co-founder of Scarborough-based Landry/French Construction Co., says the company has had to be much more selective about the projects that it goes after.

“There's only so many people you have out there,” he says.

Fewer young people to fill job openings

All industries in Maine — from fast food to financial services — are scrambling to find workers. The shortage of qualified workers in the construction industry is particularly acute. Many skilled tradesmen who were laid off during the last recession went into other industries or left the state.

Part of the issue is the aging of Maine's workforce and its dearth of young people. Maine's median age, 44.5, is the highest in the nation. And the number of students enrolled in Maine's schools has been on the decline for decades. Roughly 181,000 students attended public and private schools last year, according to Maine's Department of Education. That's down from 214,000 in 1995, and 250,000 in 1970.

Matthew Tonello, project executive and Portland-based director of Maine operations for Consigli Construction Co. Inc., says the areas that are hardest to staff are those that require large quantities of skilled craft workers at the same time. That includes millwork and framing jobs. Many carpenters are balancing commercial work with residential construction, stretching the workforce, Tonello adds. “There is a lot of wood framing happening in Portland,” he adds.

Going to new lengths to attract workers

It's not just skilled laborers that are in demand. Construction firms are also having to be creative to attract and retain the managers and office workers they need to support their growth.

Landry/French increased its management staff by 30% in 2016.

“I spend as much time looking for new people as I do for more projects,” French says.

Landry/French converted to an employee stock-ownership plan, or ESOP, in 2016 and that has helped the company attract talent, says French. It also increased internal growth opportunities for its staff members, so that new recruits see an opportunity for a career, not just a job.

“We're not just going to hire a person to be in one position for the rest of their life,” he says. “Our people can grow as we're growing.”

French, like many others, makes an effort to recruit Mainers who have moved and worked out of state at larger firms and want to return to Maine. “Those people bring another layer of expertise,” says French. “It elevates our company when we compete against national firms.”

Tonello says that Consigli works with clients to identify areas of risk and how the labor shortage may potentially affect projects. To work around the shortages, Consigli is taking measures like using more prefabricated elements for projects, offsite construction or splitting up work between contractors. Consigli also provides on-the-job training and an apprenticeship program that teaches job skills.

That has an impact on potential customers, too.

“Our clients see that the amount of job training we provide differentiates us from other companies and allows us to show that we have the capability to properly staff projects,” Tonello says.

Matt Marks, CEO of the Associated General Contractors of Maine, says his group is working with the Maine Department of Labor and the state's career and technical education schools to create pre-apprenticeship programs, particularly for skilled trades like carpentry, welding and heavy equipment operation, which would allow high-school-aged kids to get training during school vacations, and apprenticeships that they can complete once they're out of school.

Marks is also working to correct misperceptions about what it's like to work in the industry on an everyday basis and what the earning potential is here. He meets with school guidance counselors to help them understand the skills required for construction trades, and the salaries that students could potentially earn in the field.

“It's really about the industry getting out there and showing the potential income and opportunity is a lot different than it was before,” he says.

“It comes down to what we value,” he adds. “Some people have a good grasp on history and math. And other people are good at working with their hands. And that's of equal value to our society.”

Comments