Maine's 'designing women' chip away at architecture's glass ceiling

Becca Casey traces her love of architecture back to fourth grade, when she and her best friend would have fun “redesigning” shopping malls they had visited.

“Maybe we were on to something,” she says.

Growing up in a family of contractors, builders and painters also whetted her interest in the profession, as did an aptitude test she took in high school: “I was like, yep, that'll work.”

After earning a master's in architecture from Tulane University in 1996 where she also earned a bachelor's degree, Casey initially felt she had to prove herself on every job, with contractors “practically rolling their eyes” at a woman in her twenties telling them how to build something.

She's now a senior health care architect at SMRT Architects and Engineers in Portland, Maine's only large architectural firm led by a woman. Headed by Ellen Belknap since 2004, it's also Maine's largest architecture firm.

“It is something that makes me proud,” says Casey, a trailblazer in her own right as Maine's first architect credentialed in the global WELL Building Standard for advancing health and well-being in buildings.

Lonely at the top

Architecture remains a male-dominated field, starting in education where three out of five students are men as shown in a 2014 nationwide study by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. The same report found that one in four working architects and fewer than one in five deans are women, nearly four decades after that gender barrier was broken.

The higher in the profession you go, the smaller the female proportion, all the way up to the highest honors. ACSA research found that while women have been increasingly recognized since the 1980s, they received only 18% of top awards between 2010 and 2014.

To learn the reasons behind the gender imbalance, the American Institute of Architects — a Washington, D.C.-based professional organization with 23% female membership — conducted a gender diversity study in 2015.

Half of the women surveyed said that women are less likely to achieve their career advancement goals. Of those who leave jobs in architecture, women are more likely to do so to start a family or to take a job outside the field while men who leave are far more likely to pursue a more lucrative career.

Women also reported a lower job satisfaction than men in many areas, including salary, career advancement opportunities and gender equality in the workplace.

“These are cultural issues in the field that might be addressed by industry leadership,” the AIA concluded. It vowed in 2017 to make equity, diversity and inclusion a core value of its board, create best-practice guides for firms, and develop a self-assessment tool for AIA members and their firms but has mostly left it up to industry to change itself.

Paving the way

In Maine and elsewhere, female architects are making progress.

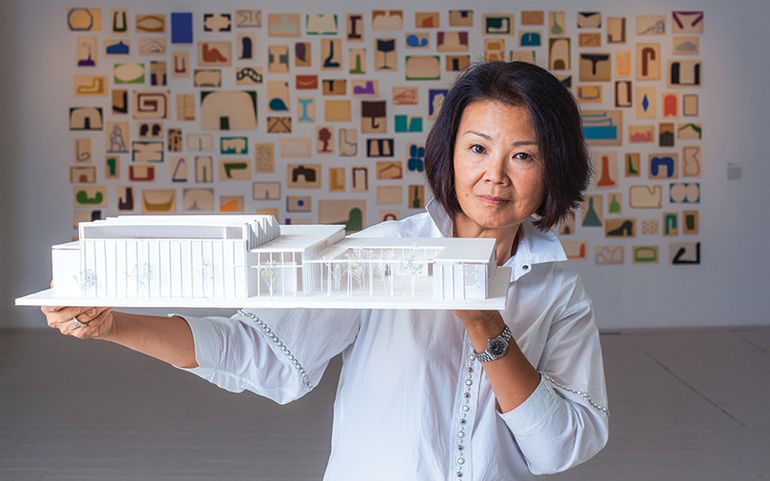

Toshiko Mori, an award-winning New York City-based architect with strong ties to the Pine Tree State, designed the Center for Contemporary Art in Rockland. She's also the first architect to receive the Farnsworth Museum's Maine in America Award for her significant contribution to Maine's role in American art.

Asked if she's had to overcome any obstacles as a woman, she replies: “The barriers are all based on perception. If one does not accept those limitations, one is ahead of the game already.”

She says she likes building in Maine because of the work ethic, pride in craftsmanship and “fundamental understanding of ecology that we all share.”

Another pioneer is Ellen Belknap, who joined SMRT is 1986 as an intern, became president in 2004 when there were seven or eight employees and was named a Mainebiz Woman to Watch in 2014. Today she leads a team of 110 in four offices, including 40 licensed architects and architectural designers.

As she advanced in her career, her engineer husband pulled back in his own career to help raise their sons.

SMRT aims to help employees achieve work-life balance by offering part-time work, summer hours and letting folks work from home when needed.

Belknap has sought to foster a culture of engagement, knowledge-sharing and collaboration. Examples include pairing people of different experience levels on projects, hosting informal sessions where employees can critique presentations before they go to clients, and starting a nine-month leadership development program last year.

“I get my energy from helping people grow,” Belknap says of the first class that just graduated. “The way those 10 came together as a group,” she adds, “they'll be friends for life.”

Nicole Rogers, who co-leads SMRT's architecture department with Dennis Morin and became an associate principal this year, took part in the first class.

She says the group did indeed bond and plans to meet quarterly.

Back in high school, when Rogers's first job was at an architectural firm, the only other woman in the office was her boss, who told her not to go into the field because it was challenging for women.

“I was like, 'I don't care,'” Rogers says. “I saw that as a challenge.”

Today, she has no regrets about sticking with it, and says that if she weren't an architect she could imagine herself as an artist or mathematician. At SMRT, where she gets to use those skills and more on a daily basis, “it doesn't matter what you are or who you are, it's who's right for the job.” She also says that until it's pointed out, no one really thinks about the fact that the firm is run by a woman.

Others, like architectural designer Alyssa Phanitdasack, say it matters a lot even though “I wish we lived in a world where it didn't make a difference.”

The 2010 Bowdoin College graduate, who joined SMRT in November 2017, remembers when a male colleague in Los Angeles questioned her ambition of becoming a design lead one day because she's a woman.

“I don't intend to trail-blaze,” she says. “It's just what I want to do.”

A visual arts and biology major in college, she blends both interests through projects such as STEM Center addition for the Hebron Academy and medical office buildings in New Hampshire she's now designing.

Other career paths

Like Phanitdasack, Becca White was an undergraduate biology major before turning to architecture. The 31-year-old started at Carol A. Wilson Architect in Falmouth this June and says she's not experienced any gender bias from contractors in Maine despite it also being a male-dominated profession.

“Part of that is Carol's passionate attitude,” she says.

Both she and her boss laugh about the fact that they both enjoy woodworking as a hobby, while the male in their office has other skills.

“It's a small team and we work well together,” Wilson says during an interview outside the Gilsland Farm Maine Audubon Center that she co-designed, a modern shingle-style eco-friendly building before going green became trendy.

Wilson, who's been in the profession since 1982, has come a long way since her college admission interview at North Carolina State University, whose dean caught her off guard by asking if she wanted to marry an architect. Wilson chose it as a major a week into freshman year and has been going strong ever since, earning several honors over the years including Maine's first AIA Fellow. (There are now two other women and three men.)

“It basically says you're on the right path,” she says, adding: “The beauty of architecture, and why I love it so much, is that it's right brain and left brain.”

Fellow industry veterans Nancy Barba and Cynthia Wheelock, of Portland's Barba + Wheelock Architects, relish that aspect as well. “I don't know if women are better suited to it,” Wheelock says, “but we have great women designers and leaders in the architectural profession.”

Bright future

Women of all experience levels interviewed for this article see a bright future for younger peers starting out today.

“Maine has a strong design community and we are always looking for people to get involved and share new ideas,” says Kathryn Wise, manager of architectural services at L.L.Bean and chair of AIA Maine's Emerging Professionals Committee. “It is never too early or late to get involved in the profession.”

Comments