Spiking costs creating a pricing nightmare for construction companies

Photo / Tim Greenway

Nathan Szanton, president of Szanton Co., and Amy Cullen, the firm’s development officer, at the site where the company will be develop affordable housing in Bayside in Portland.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Nathan Szanton, president of Szanton Co., and Amy Cullen, the firm’s development officer, at the site where the company will be develop affordable housing in Bayside in Portland.

The requests for proposals are out for the Szanton Co.’s Portland Bayside mixed-use development project.

That’s usually a heady time in the development process — a big step forward after years of planning. But company president Nathan Szanton is nervous. The huge rise in the past couple of years in construction costs mean that bids may come in higher than what the project can bear.

“There are a lot of sleepless nights waiting for bids to come in,” he says.

Szanton has been in business for more than two decades. “I’ve never seen construction costs change as fast as I have in the last year or two,” he says.

Szanton Co.’s residential projects include a mix of market-rate and affordable units, and there is little wiggle room to increase rents as construction costs rise.

If bids come in too high, “The project would probably not go forward, and all the work we’ve put in would probably go down the drain,” Szanton says.

Szanton isn’t the only one having sleepless nights. The high cost of construction in Maine is affecting development projects big and small.

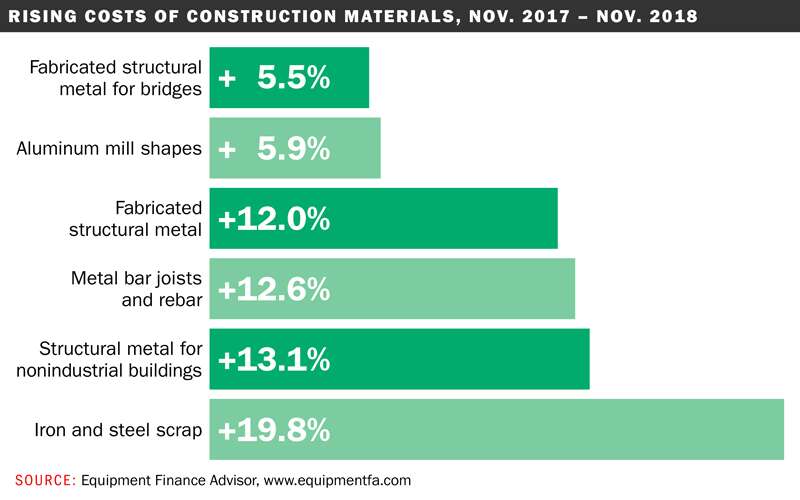

Factors include the strong economy and demand for new real estate, a shortage of skilled labor and tariffs on steel and aluminum, which have driven steel prices up 20% and aluminum up 6%.

As the price tag on projects changes almost daily, developers, construction companies and contractors are finding ways to cope.

“Any contractor you talk to is going to say they’re severely impacted by price pressure,” says Scott Tompkins, Cianbro director of business development.

The large construction manager

Pittsfield-based Cianbro, Maine’s largest construction firm, has a big 2019 ahead. It broke ground last month on a 179,000-square-foot Maine Veterans’ Homes residence in Augusta and renovations on the Maine Correctional Facility in Windham will start this summer.

When the Maine Veterans’ Home residence was approved by the Augusta Planning Board in 2017, the cost estimate was $76 million. By the time Cianbro’s heavy equipment rumbled onto the site last month, it had risen to $90 million.

As a construction manager, part of Cianbro’s job is to stay on top of costs and make the project work, Tompkins says.

Cianbro late last month issued RFPs for subcontractors on the prison expansion, which has been in the works for more than a decade. It includes seven new buildings totaling 189,000 square feet of new construction and 128,000 square feet in renovations at the 50-acre site on Route 26. In 2016, a $149 million bond issue was approved for the project — how much the costs have increased since then won’t be done until the bids come in. Groundbreaking is expected in June.

Cianbro will work hand-in-hand with the Portland architecture firm SMRT, which designed the project. “We’ll keep it within reach of what we know we have to spend,” he says.

Cianbro manages costs with “lean building” principles, which involves pre-fabrication offsite, carefully choreographed movement of materials to a site and constant assessment over where a project is and what’s needed.

Cianbro is also in a position to help out subcontractors when labor numbers fall short. The company’s Cianbro Institute, in Pittsfield, offers 75 workforce-training courses.

“We can self-perform some work on a project,” Tompkins says. “Construction managers generally don’t perform the work, unless it makes sense to do it.”

The company also has fabrication shops, which help with the cost of steel.

“We’re in a little bit of a unique position in that we’re equipped to mitigate [some of the issues],” he says.

The affordable housing developer

Szanton Co. also has a busy year planned. The company is just wrapping up the Hartley Block on Lisbon Street in Lewiston, a mixed-use building that has 63 residential units and 4,000 square feet of retail.

Across the river, in Auburn, ground has been broken on the 53-unit 48 Hampshire project.

And then there are those bids in Bayside for a seven-story, 46,000-square-foot mixed-use project, with 55 rental units and ground-floor retail.

“All of them have been heavily affected by the rise in construction costs,” Szanton says.

While higher costs have not forced Szanton to scrap any projects, “it has squeezed us,” he says.

When costs come in too high, developers do “value engineering” — making adjustments to things like type of carpeting, or insulation.

“We do what we can do to save money,” he says.

But it’s possible bids can come in too high for that to make a difference.

“Once the bids come in, we assess,” Szanton says. “If it’s 5% too high, we can value engineer. If they’re 15% too high, that’s a major problem. That’s more than you can value engineer.”

He says it’s possible to go to financing sources to tweak the budget, but that also has its limits.

The most likely scenario? “The project would probably not go forward,” he says.

Because the rents for the affordable housing are pre-determined, rents can’t be increased to cover higher costs. “We’re boxed in,” he says.

The historic building redeveloper

Developer Kevin Mattson of Dirigo Capital Advisors said the rising cost of construction hit home for him last year, when he had to buy 25 apartments worth of kitchen cabinets for 25 units in the Saco Mill Complex in Saco.

He was told that he should agree to a fixed price, because in the months it would take to get the cabinets, the price would increase by more than half.

“I’ve been doing this a long time, and I’m used to seeing year over year price increases, but this is double digits,” Mattson says. “It’s nuts.”

The biggest area that affects him is with aluminum and steel.

“Do you have any idea how much aluminum and steel are used in construction? It impacts everything. It’s everywhere,” he says.

When he recently had to buy a chiller — a large piece of a building’s heating and cooling system — for the 300,000-square-foot Ballard Center in Augusta, he was confronted with the same issue he had with the cabinets. He was told that if he didn’t place the order by a certain date, the price would go up 5%.

“That’s a critical component. I had to have it for the building. And it’s made entirely of aluminum,” Mattson said.

Mattson says, though, that in a way the situation helps developers of existing buildings.

“It costs a lot more to build from scratch,” he says.

He also says the issue is tougher on rural Maine than the Portland area.

“If you’re doing a project in Caribou that’s going to cost 20% more, it’s a lot harder to recoup that cost,” he says. “It’s disproportionate.”

Balancing act

Coupled with the “big three” issues — tariffs, labor shortage and lack of available subcontractors because of the economy — are some sub-issues.

Mattson cites the shortage of long-haul truckers.

“Every single thing you get comes on a truck,” he says. Lack of truckers makes transportation costs higher and delays deliveries.

Szanton points out a higher labor wages in nearby states, like Massachusetts.

“If someone can earn one-and-a-half times in Massachusetts what they can in Maine, they’re likely going to take the job in Massachusetts,” he says.

The construction boom in the state was bound to result in eventual pushback, those in the industry say.

It’s a balancing act, says Tompkins of Cianbro, to make sure the finished product “doesn’t suffer too greatly because of price escalation.”

“You recognize issues early, make changes,” Tompkins says. “You get in front of it.”

As the skilled worker shortage can make projects take longer than they normally would, Szanton says he is grateful to find contractors who can work well to accommodate issues.

Three or four years ago, the Hartley Block project may have taken 11 months. But a contractor has to get subcontractors — plumbers, electricians, masons.

“The project might need 10 guys, but they might send five guys, because that’s all they have because they’ve got other projects going on,” Szanton says. “You can't just open up a big can of workers.”

Hebert Construction, the contractor on the Hartley Block, agreed to a 13-month project instead of 11 months to build in slack for issues that might be caused by higher costs.

The building began welcoming tenants March 20, as planned.

Szanton credits Hebert’s effort, saying, “It took a lot of really skilled project management on their part to keep on schedule.”

0 Comments