Maine continues to experience a severe shortage of housing, at all price levels, and the rise in rental and purchasing prices still outpaces income adjustments for most Mainers.

The most recent comprehensive study (released in 2023) on what’s being called a crisis by housing advocates, policy makers, real estate and construction professionals along with everyone in search of housing — found that Maine needs 84,000 new homes by 2030 in order to meet demand. That level of building calls for roughly doubling current production.

To meet these goals, Maine is going to need further funding and technical support from state government, input and tracking from municipalities, and work at both the state and local level — by community officials and citizens — to streamline the approval process.

With 2030 on the horizon, Mainebiz has been looking at what progress the state is making in meeting the need, as well as the challenges that still make finding housing that’s affordable so difficult for so many.

How we got here

“For years we haven’t been building housing fast enough in Maine, and we’re falling farther and farther behind,” says Portland-based developer Nathan Szanton, who has created close to 800 apartments in Maine and New Hampshire in the 20-some years he’s been in the business.

New housing starts have been restricted largely by rapidly escalating costs for material, which is beyond local control. Szanton notes, “The current construction cost environment makes it impossible now to build market-rate without charging very high rents.”

In addition to overly cumbersome local approval processes and a shortage of construction workers, increased demand has been a huge factor. In the past four years, nearly 63,000 new residents (according to the latest U.S. Census), sought refuge in “The way life should be” state, in the wake of the COVID pandemic. Interestingly, 78% of our new neighbors moved here from other states, and 22% from outside of the U.S.

In-migration has been most keenly felt in Cumberland and York counties, where many higher income new residents have been able to purchase and rent, effectively reducing supply for lower-income families. Additionally, housing stock has been affected in these counties by homes being used only seasonally and properties being converted for short-term vacation rentals.

One example is Kennebunkport, where 51% of houses are owned by people who are not full-time residents.

The need is acute

Szanton has focused on projects that include a percentage of “affordable” units (priced at varying percentages of area median income) which utilize tax credits and subsidies, which is the only way he says projects can “pencil out” in this economy. He’s completing a 63-unit apartment building in Portland’s Libbytown neighborhood, in which all of the units are reserved for lower-income residents. Targeted for completion in July, the building is not yet being leased but he’s already received 230 inquiries — for 63 apartments — without advertising.

“The need is more acute now than it’s ever been,” Szanton told us. “We’ve never had any problem leasing our buildings, but there’s a desperation now that we haven’t seen before.

“Maine is desperate for housing. It’s like taking a dry sponge and dripping a few drops of water on it, and it just absorbs it instantly.”

Szanton’s experience is consistent across the state, but as Mainebiz has checked in with policymakers and housing advocates, we’re seeing some cautious optimism that housing availability could be growing over the next few years, and more supply traditionally brings prices down.

Single-family home prices have stopped rising, for now

Single-family home starts are being added in very small numbers, infill builds of just a few units. But prices of existing homes have seen decreases since peaking in the low $400,000 range last year.

The median sales price of a house in March was $376,260, a slight dip from $381,500 in February. By comparison, the median sales price for March in the Northeast was $468,000.

Currently a household needs an income of $100,000 to afford the median home price in our state. Maine’s median household income is $63,200.

There’s growth in the rental sector

While single-family home starts are rare, thousands of apartment complexes and condos, both “affordable” (priced to not exceed 30% of household income) and market-rate, have recently been built across the state and there are many more under construction. Mainebiz has been keeping tabs on projects in more than 30 communities.

MaineHousing, a state agency that finances lower-income projects, completed 775 affordable housing units last year. Another 1,005 units are in progress.

Two of the largest projects in the state are at Brunswick Landing and at the Downs in Scarborough. Brunswick Landing is a 3,200-acre mixed-use community at the former site of Brunswick Naval Air Station, where developers have built or refurbished a total of 2,250 housing units, across all types and price categories. Monthly rents range from $1,500 to $3,000.

At the Downs development in Scarborough, 622 housing units have been built so far; a total of 1,500 will be completed over the next 7 to 10 years. Units range from single-family to apartments and condos, and some are reserved for lower incomes. Rents for two-bedroom market-rate apartments average $2,450 to $2,745.

Portland-based Developers Collaborative continues to create multi-family housing, much of which is classified as affordable. Projects have included new builds and repurposing of older properties in Rockland, Portland, Rumford, Augusta, Lewiston, Auburn, Bridgton and Belfast, to name just a few.

The city of Sanford has multiple projects under construction at several price levels, including units being built in some of the city’s repurposed mills.

At Brooks Edge Farm development in Westbrook, 118 condominium units have been started. Like many condo projects, developers are pre-selling in phases, to finance construction costs. Also in Westbrook, Avesta Housing has broken ground on a 61-unit affordable housing development for residents age 55-plus.

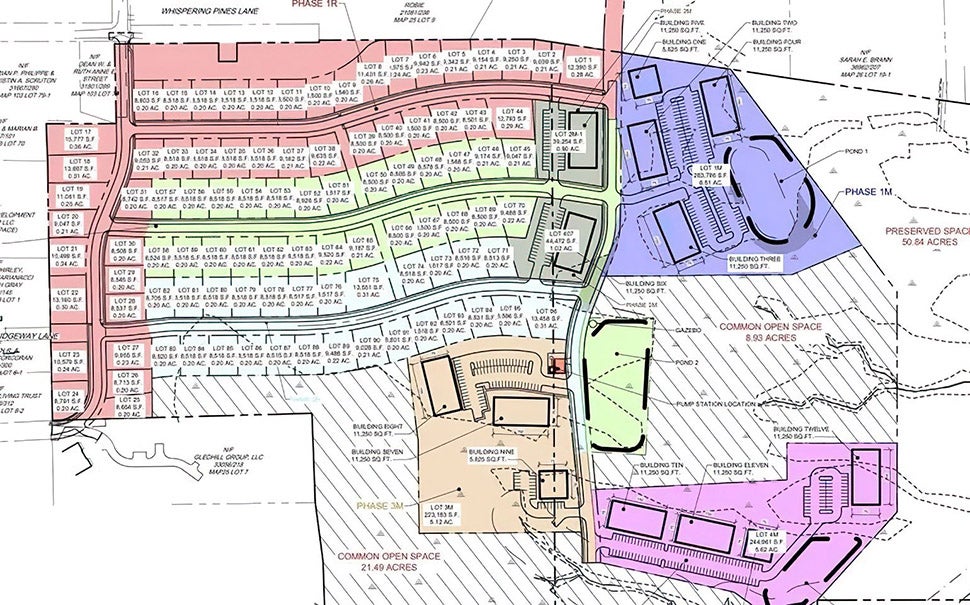

Gorham is poised to see new construction of 391 homes — 295 multi-family units and 96 single-family homes — in the Robie Street subdivision, which has just broken ground.

Kevin Jensen, the town’s economic development director, sees the diverse mix of options in the Robie project as key for growth.

“When we think about young professionals and empty-nesters, those are customers for our small business retailers, restaurants and professional services. They could also be employees or business owners in Gorham,” he says.

In Portland, fees have stalled some large builds

Thousands of apartments have been built in the past few years in Portland, some of which are market-rate, others are lower-income. But large builds have been encumbered by the city’s Inclusionary Zoning Ordinance which requires that projects with 10 or more units (approved after December 2015) must make 25% available to lower-income households or pay an in-lieu fee of nearly $183,000 per unit.

Broker and developer Tom Landry says the ordinance has been counterproductive.

“This is another well-intended civic action leading to unintended consequences, less housing for all types and less affordable housing. Remove this, make further edits to ReCode, and the free market will be unleashed to address this imbalance between supply and demand,” Landry says.

Portland’s Thompson’s Point has in the works 255 market-rate apartments which are not restricted by inclusionary zoning, as that project was approved as part of the complex’s master plan in 2012, and inclusionary zoning was not adopted until 2015.

More construction workers could make a difference

While the state had been losing skilled carpenters and electricians to aging and to the expanding energy industry, MaineHousing reports seeing construction employment grow by 7.3% from 2023 to 2024 and projects construction capacity is growing.

One of the recommendations from the January 2025 study, “A Roadmap for the Future of Housing Production in Maine,” is to provide “long-term, dedicated funding for apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship programs in the trades.”

Consigli Construction Co., with a Portland office, has been innovating training and outreach programs to grow the workforce, including efforts to bring more women into the industry.

Legislative action has been effective, but more needed

Since 2019, Maine has provided $280 million in funding to support construction of affordable apartments.

LD2003, passed by the legislature in 2022, directed municipalities to increase housing opportunities by easing restrictions on density, including allowances for more ADUs (accessory dwelling units on existing home lots) and simplifying the regulatory process, which has been identified as a key stumbling block to more housing creation.

“MaineHousing has been able to significantly ramp up affordable housing production in Maine over the last several years,” Dan Brennan, the a director, notes, thanks to subsidies and federal pandemic aid.

“But we’re now in the final stages of exhausting the available state subsidy. Without additional new sources of subsidy, the production of new affordable housing is likely to slow down.”

The 4% state low-income housing tax credit has been integral to development, but there is a sunset provision in the law, and for that to continue to be available, the legislature needs to extend or reauthorize it, which appears likely.

State Rep. Traci Gere, D-Kennebunkport, who chairs the Housing and Economic Development Committee, notes, “In addition to the 4% tax credit program, the Rural Affordable Rental Housing program and the Affordable Home Ownership program need continued funding.

“We’re also considering proposals for a state bond for housing and an increase in the real estate transfer tax on sales of homes over $1 million. First-time homebuyers would be exempted.”

Hilary Gove, with the Department of Economic and Community Development, adds that the Housing Opportunity Program recently awarded grant funding to 21 municipalities and 15 service providers to address local land use barriers and community opposition to certain housing developments.

Additionally LD1184, moving through committees now, would create the first statewide database to track annual housing creation from every town with a population over 4,000.

(MaineHousing and the city of Portland maintain databases for their projects, but there hasn’t yet been a vehicle for gathering numbers statewide.)

More work has to be done at the local level

Gere stresses the importance of community leadership.

“In Maine and across the country, land use decisions about the location of housing are made at the local level. Our population is aging, and if we want our communities to be sustained into the future, we need to build housing that young people and young families can afford, in town centers with access to services.

“Zoning and land use policies can create barriers, especially in our coastal areas, to anything but high-end housing, and for seasonal residents. The comprehensive planning process that state law mandates is burdensome. It can take a community as much as five years to bring people together to decide on what type of housing they want to allow.

“Things get dragged out for years and nothing happens. Then a small group of people who don’t want to see any development come out in opposition, and we don’t currently have an appeals process for when these projects get shut down. New Hampshire does.

“In the meantime, we have communities that are trying to hire doctors, who can’t move here because they can’t find housing.

“Having a locally agreed upon vision for housing that is affordable to people who live and work in our communities, with specific understanding on where it can be built, is essential to continuing to make progress on Maine’s housing challenge.

“This is hard work, but I know we can do it.”