Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Fishing for a future | A Searsmont entrepreneur's aquaculture innovation is welcomed in foreign waters while the U.S. plays catch up

Photo/Whit Richardson

A crane readies a MicroPod, built by Searsmont-based Ocean Farm Technologies, for deployment at an offshore shrimp farm in Guayamas, Mexico

Photo/Whit Richardson

A crane readies a MicroPod, built by Searsmont-based Ocean Farm Technologies, for deployment at an offshore shrimp farm in Guayamas, Mexico

In the dingy shipyard of Guaymas, Mexico, several men gather around a black, geodesic cage large enough to encapsulate a Hummer. The men, in their T-shirts and jeans, bolt one triangular section to another as the black sphere continues to take shape. Covered in a fine black wire mesh, the panels offer welcome shade on a scorching afternoon in November. On the other side of the yard sit two giant domes made of the same triangular panels, two halves of a cage that dwarfs the one the men are working on now.

The black panels, stacked chest-high around the yard, took a cross-continental trip from a small manufacturing facility in Searsmont, Maine, to get to this patch of sandy soil on the Sea of Cortez, the body of water on the west coast of Mexico separated from the Pacific by the Baja Peninsula.

Now nearly empty, the Guaymas shipyard once bustled with activity. It built the fleet of trawlers that has hunted the Sea of Cortez’s abundant shrimp populations for the past few decades. Today, the rusting hulks of abandoned cranes — appearing like something out of “War of the Worlds” with their blue steel legs meeting the ground a hundred feet below cabins where pigeons now roost — tower above these workers building something new.

Most of those shrimp trawlers sit rusting like the cranes. Nearby, there are roughly 20 trawlers tied to a dock, alongside piles of what looks to be years’ worth of trash. The fishermen who congregate on the docks, some fixing nets, others smoking cigarettes and socializing, seem unconcerned that it’s the middle of shrimp season. Out of all the trawlers, only one crew is busy stocking their ship to prepare for a trip to sea.

One of those idled fishermen could have been Oscar Valdez, if it wasn’t for those cages from Maine. Valdez, a lean, dark-skinned man with silver-streaked black hair and a mustache, began fishing when he was a young man and slowly built a small fleet of trawlers. His company, Pesquera Delly, grew to a peak of 11 trawlers, and also spun off another company to build a seafood processing plant. But as shrimp fishing grew more difficult as more boats competed for an exploited resource, Valdez started searching for alternatives. What he found was a novel method to farm shrimp instead of hunt for them. Farming shrimp in artificial ponds onshore is common along the coast of Sonora, the Mexican state where Guaymas is located. But when Valdez’s eye settled on the AquaPod, he saw untapped potential for farming shrimp in the open ocean.

Ocean Farm Technologies is the company in Searsmont, Maine, that is quietly manufacturing the AquaPods, designed to withstand the rough conditions of the open ocean and allow entrepreneurs like Valdez to raise their livestock several miles offshore as opposed to conventional fish farming on land or in near-shore areas.

Ocean Farm Technologies Inc.

114 Higgins Rd. N., Searsmont

Founded: 2005

Founder and president: Steve Page

Services: Aquaculture equipment, including offshore containment systems

Employees: 9

Revenue, 2009: $1 million

Contact: 1-888-540-5554

www.oceanfarmtech.com

Valdez used a Mexican government program to trade in four of his shrimp boats for $100,000 apiece and used the money to buy three AquaPods, which cost approximately $140,000 each. With the AquaPod, Valdez figures he will be able to harvest 30 tons of shrimp per cage per cycle, of which there could be as many as three a year. He says his trawlers never brought in that amount per year. But trading in his traditional boats for new-fangled fish cages was still a gamble. “It was necessary to take the risk because I’m having problems with the fishing. I’m not making business,” Valdez says, sitting on a recent morning in his office inside his company’s seafood packaging plant in the industrial section of Guaymas. “We are lots of boats, so obviously I had to take a decision of what to do. Right now we are in times to initiate something before this collapse and we have more serious problems. So, you got to start generating those options of what to do. So I thought, well, it’s the moment to change.”

Steve Page, founder and president of Maine’s Ocean Farm Technologies, visited Mexico in November to help Valdez’s company deploy the cages now under construction. Page stands next to one of the giant domes of the AquaPod with Valdez and another man, a veteran of the region’s shrimp farming industry, which has traditionally operated onshore in artificial ponds. The men talk about the size of the mesh to ensure the smallest shrimp can’t escape and about the doubts some have about farming shrimp in submerged cages. While some claim shrimp need to rest on the ocean bottom — or the bottom of an artificial pond — Valdez believes that’s not the case. Page agrees. “It’s a good business,” Page says about farming shrimp onshore. “But this is a better business.

“I hope so,” Valdez says with a laugh. His company’s significant investment in this relatively untested technology depends on it.

Growing pains

Pesquera Delly already has one of its 3,600-cubic-meter AquaPods deployed two kilometers off nearby San Carlos that has produced one harvest of approximately 13 tons, or 130,000 adult shrimp. Unfortunately, the expected yield was supposed to be closer to 40 tons. The culprit? Hurricane Jemina, which hit this part of Mexico in September. No one is sure how the shrimp escaped from the cage, though it seems the hurricane’s strong currents got the best of the AquaPod, leading Page’s team to design a new mooring system.

Page designed the AquaPods to farm seafood in offshore environments. What “offshore” means, however, is open to interpretation. At its basic level, it means a fish farm exposed to the elements of the open ocean, and is used to distinguish it from conventional ocean aquaculture, which typically involves surface net pens in the shallow water of sheltered bays and coves. But, offshore aquaculture is so new that there are no absolutes — for instance, Page didn’t have shrimp in mind when he conjured the AquaPods — and Ocean Farm Technologies finds itself in a position to revolutionize the industry. “I think this has a very good chance of working out, but it does point out that we should not be limited in looking at what species of seafood can be grown in these containment systems,” Page says. “Part of my dream all along has been not only to grow fish, but also grow shellfish on the containment system itself … lobsters, other crustaceans and seaweeds. The ocean farm of the future will not be just one species or another. It’s going to be polyculture. It’s going to be … sea vegetables and seafood.”

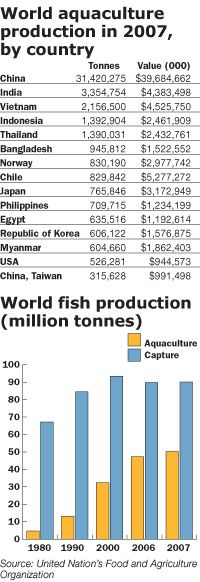

Last year marked a watershed moment for aquaculture. For the first time, aquaculture supplied half the world’s seafood, approximately 60 million tons (or 50.8 million tonnes, also known as metric tons) valued at $70 billion, according to a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The portion of that farm-raised seafood that comes from the United States, however, is minuscule, less than 1.5%. China, on the other hand, produced 70% of that 60 million tons. Despite its vast coastlines and marine heritage, the United States has fallen behind in producing its own seafood. The United States imports 81% of the seafood consumed here, nearly seven million tons a year, resulting in a seafood trade deficit in 2008 of $9.4 billion, the country’s third-largest trade deficit behind oil and automobiles. With the demand for seafood expected to increase over the next several decades and wild fish stocks struggling from overfishing, it appears that aquaculture’s role in providing seafood will continue to increase. The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization expects aquaculture to supply 60% of all seafood by 2020.

Regulatory roadblocks

But whether a domestic industry will contribute to that increase is anybody’s guess. Aquaculture has been present in Maine’s coastal waters since the 1800s, and the first laws governing aquaculture in the state date to 1905, according to the Maine Department of Marine Resources, the regulatory body that oversees Maine’s aquaculture industry. Aquaculture as we know it today began in Maine in the 1970s.

Maine’s aquaculture industry, which mostly takes the form of farm-raised salmon and mussels, harvested roughly 10,200 tons in 2008, according to DMR. A 2003 economic impact study estimated the industry generates $82 million in direct sales and revenue annually, and has a $130 million impact on the state’s economy, according to the Maine Aquaculture Association. But despite Maine’s existing aquaculture industry and its traditional working waterfront, Page has had very little luck selling his AquaPods in his own backyard. “Why do I have to travel to all these Third-World places to sell my product?” Page asks. “Why isn’t Maine doing this?”

Page, a veteran of Maine’s salmon-farming industry, says lack of a federal regulatory framework for permitting fish farms in federal waters, which extend from three to 200 miles offshore, and an almost certain litigious process means investors shy away from pursuing an offshore fish farm in Maine or the rest of the United States. The fact that no one has proven that raising fish in capital-intensive offshore farms in the cold waters of the North Atlantic is an economically viable business model only adds to investors’ wariness. “I’m optimistic in the long run. I’m pessimistic in the short run,” Page says while standing under the half-completed AquaPod in the Guaymas shipyard, hammers and wrenches working away in the background. “I really don’t see it happening anytime soon. It’s going to be a long, long legislative process to enact legislation, and once legislation is enacted it’s going to be a long, long regulatory process to do the rule making. So, I really don’t see anything happening in the U.S. for four to five years.”

For this reason, Page realizes his best growth opportunities lie outside the United States, where governments have been more open to the prospects of offshore aquaculture. Since 2008, Ocean Farm Technologies has shipped AquaPods to companies in Puerto Rico, Panama, Mexico and South Korea. Interest has come from all over the world. Turkish businessmen paid Page a visit during a snowy day last winter to check out the AquaPod. And within the last couple of months, the governments of Ecuador and Indonesia have inquired about using the smaller cages, dubbed MicroPods, to help struggling fishermen become farmers, a potential use that has been recognized in Maine, as well. “The transition from informal fishermen to fish farmers is really catching on worldwide right now,” Page says. “It just seems to be an idea whose time has come.”

While the tools may be new, the idea of farming the oceans is not. That prescient explorer of the deep blue, Jacques Cousteau, promoted farming the oceans in the early 1970s. “With Earth’s burgeoning human populations to feed, we must turn to the sea with new understanding and new technology,” Cousteau said in his 1973 television show “The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau.” “We need to farm it as we farm the land.”

Pushing limits

One pioneer of the offshore aquaculture movement close to fulfilling Cousteau’s vision is Brian O’Hanlon, a 30-year-old New Yorker who grew up in a family of seafood dealers. O’Hanlon became interested in aquaculture young, hatching red snapper in his parents’ basement when he was 17. Now, 13 years later, O’Hanlon is in a motor boat heading through the Caribbean harbor of Puerto Lindo, a small fishing village on Panama’s north coast. It’s here that O’Hanlon, president and founder of Open Blue Sea Farms, has chosen to literally test the waters with what he claims is the largest offshore fish farm in the world. Since last August, Open Blue Sea Farms has been farming cobia, a white fish similar to halibut, nine miles off Panama’s coast in submerged cages designed by OceanSpar, a Washington-based competitor of Ocean Farm Technologies. It is the most remote and exposed offshore fish farm in the world, O’Hanlon says. On this day, O’Hanlon isn’t heading all the way to the farm, which is a long, bumpy motor boat ride over the horizon. Instead, he’s checking on a large cargo ship that’s preparing to tow three more OceanSpar SeaStations out to the farm site.

On the way to the rusted blue hull of the “Pristine Oceans,” O’Hanlon’s motor boat passes four of Page’s MicroPods, which are almost totally submerged in the bay. One is full of young cobia, another is made with a copper mesh netting that O’Hanlon is helping Page test for better performance in reducing the amount of algae and seaweed growth on the cages. O’Hanlon began his quest to develop a successful offshore fish farm several years ago with a demonstration project using AquaPods in Puerto Rico. The demonstration project succeeded and he began looking for sites for a commercial-scale project in 2005. Puerto Rico, a territory of the United States, is governed by U.S. law. O’Hanlon says it was a good place for the demonstration project, “but in the end it didn’t turn out to be a great place to build a large-scale operation. There was a lot of bureaucracy. Too many agencies involved. No clear permitting process or framework for the permits.”

Pesquera Delly

Director: Oscar Valdez

Project site: Two kilometers off the coast of San Carlos, Sonora, Mexico

Species farmed: Shrimp

Size of farm site: 248 acres

Use of AquaPods: The company has deployed one 3,600-cubic-meter AquaPod and is preparing to deploy two more. The company also intends to deploy eight smaller MicroPods stocked with shrimp.

Open Blue Sea Farms

President: Brian O'Hanlon

Project site: Nine miles off the coast of Puerto Lindo, Panama

Species farmed: Cobia

Size of farm site: 2,500 acres

Use of AquaPods: The company has deployed six MicroPods at a near shore site

In addition, Puerto Rico’s transportation and labor costs were high and, perhaps most importantly, the availability of suitable deep-water sites was limited. Not to mention its location in hurricane alley. “Panama, on the other hand, has a very small government, very clear process for permitting, very supportive government and many available sites for building these farms outside the hurricane region, so we can build larger facilities without the risk,” O’Hanlon says, also noting the country’s inexpensive transportation options and lower labor costs.

One of O’Hanlon’s goals is to create a farming system that can be replicated around the world, including off the coast of Maine. But, while O’Hanlon says his company is the closest to proving the economic viability of an offshore farm (he estimates reaching profitability by the end of 2011), he says there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done, especially around automating processes.

But even if the model were ready, O’Hanlon doesn’t think the United States will be for five to 10 more years. First, the United States needs to create a regulatory framework that balances industry growth with environmental and conservation concerns. Then it needs to address groups within the country that are opposed to the expansion of ocean aquaculture. “We’re really trying to produce a fish in a sustainable and responsible way and I think the U.S. itself has a responsibility to — in one way or another — produce more seafood rather than rely on the rest of world for it,” O’Hanlon says while sitting under a gazebo on a hill overlooking the Caribbean.

The opposition O’Hanlon’s referring to comes from groups such as Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based group ardently opposed to the expansion of ocean aquaculture (see “Offshore aquaculture detractors,” page 14.) Marianne Cufone, director of Food & Water Watch’s fish program, agrees that the United States should produce more seafood, but says ocean aquaculture is not the answer. Instead, Cufone touts land-based aquaculture systems as a sustainable model for supplementing the domestic seafood production without the risk of disease, fish escapes and pollution. “We’ve been struggling for so many years to try and make [ocean aquaculture] work, and it simply hasn’t been working well,” she says.

O’Hanlon’s ideal solution would be to invite all who oppose offshore aquaculture to his farm to see it firsthand. “I’ll be the first to admit, we’re not perfect, but the point is that what we’re trying to do here is do it better and fix the problems that do exist and do remain,” he says.

For the moment though, O’Hanlon is focused on making sure everything is ready to tow the cages out to sea. He heads the motor boat out of the harbor to test the currents that could potentially drag the SeaStations toward shore. He has brought a white plastic bucket attached to a buoy and a GPS system. At three pre-designated spots, O’Hanlon fills the bucket with water and lets it sink, weighted by an attached metal shackle. O’Hanlon marks the spot on his GPS, then waits as the boat and buoy drift on the current toward shore. After 10 minutes, O’Hanlon fetches the buoy, marking the GPS waypoint to see how far the bucket has traveled. There are more sophisticated methods of testing the strength of a current, but O’Hanlon says this method works just fine for now. The irony isn’t lost on him. “Believe it or not, you’re looking at one of the most advanced fish farms in the world,” he says.

While O’Hanlon pursues the long-term viability of offshore fish farming, Oscar Valdez needs more immediate returns. His nearly dozen shrimp trawlers were bringing in fewer shrimp every trip, while at the same time his costs were increasing. He needed to make a decision. “I have two options in fishing, to produce more and sell cheaper, or just to lower my cost to the ground. I can do none of those things now,” Valdez says. He explains that a boat costs about $500,000. “If the boat costs me that, how much shrimp must I capture to pay for the boat? I cannot pay for the boat. Instead, the cage cost me $140,000 and with some time I’ll be able to pay for it.”

Gustavo Valdez, Oscar’s son and operations manager for Pesquera Delly’s nascent aquaculture division, sheds a bit more light on the predicament that shrimp fishermen face in the Sea of Cortez. “Usually the best part of a season is the first three or four months of a six-month season, and here we are two months down the road from the start and half the fleet is already tied to the docks because it’s just not economically viable to continue fishing,” he says. “So, it’s a matter of whether you sit around and leave your boats, your assets, to do nothing for the rest of the year or you find a way to keep producing in a way that allows you to be economically viable.”

It’s that economic reality that Gustavo Valdez believes will drive the aquaculture industry’s movement offshore. “If you’ve been involved in fishing your whole life and you have all your experience in that type of business, the next logical step is aquaculture.”

Whit Richardson, a writer based in Friendship and former Mainebiz editor, reported this story through a World Affairs fellowship from the International Center for Journalists in Washington, D.C., funded by the Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation. Fishing for a Future Part 2 looks at aquaculture’s impact in Maine as traditional fishing transitions to fish farming.

Offshore aquaculture’s detractors

Not everyone is convinced that offshore aquaculture is the answer to the world's seafood problems. One of its most vocal critics is Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that believes open ocean aquaculture should be prohibited in U.S. waters. The major concerns of organizations like Food & Water Watch are the environmental impacts from offshore farms, including fish waste, excess fish feed, antibiotic use, the potential for fish escapes and the spread of disease to wild fish populations. Many of these same points have been contentious in conventional fish farming in near-shore, shallow environments, some with disastrous consequences.

Chile's salmon farming industry, for example, collapsed last year after infectious salmon anemia spread throughout the industry's fish cages and wiped out millions of salmon. The rapid spread of the disease was blamed on poor management and fish overcrowding.

Questions of sustainability

Population controls, environmental waste

Wenonah Hauter, executive director of Food & Water Watch, recently released a blistering response to the National Sustainable Offshore Aquaculture Act of 2009, which attempts to set up a regulatory framework to permit offshore fish farms in U.S. waters. California Rep. Lois Capps introduced the bill in mid-December in the House. "Rather than continue with legislation to regulate (and thus allow) ocean fish farming, Rep. Capps should instead support legislation that would prevent the growth of this industry," Hauter says. "To supplement U.S. seafood production and increase green jobs, a much more sustainable approach is necessary."

Hauter suggests the more sustainable approach to domestic seafood production is through land-based, recirculating systems that would make escapes impossible and allow the fish farmers to treat the water used in the farm.

Another skeptic of offshore fish farming, Paul Molyneaux, a former Down East fisherman who now writes about the fishing and aquaculture industries, questions the basic premise that farming carnivorous species of fish, such as salmon and cobia, can be sustained. The fish feed that farmers give to these carnivorous species contains fish meal and fish oil, which come from wild fish such as menhaden and anchovies, creating the potential to exploit those species in the pursuit of farming the others.

Molyneaux expresses concern, too, over fish waste, which can build up in the shallow areas where conventional fish farms are located. But moving offshore where the waste is carried away by strong currents isn't the answer, says Molyneaux. "The basic idea is that we depreciate natural capital and enter it onto the books as profit. Is the water that enters an aquaculture pen worth more than the water that flows out laden with feces, chemicals, viruses, etc.? Of course it is," Molyneaux says. "Then where is that depreciation figured in? It's not; it's figured in as profit. It is like letting trucks run our roads without paying a premium tax."

Formulating answers

Matters of scale, understanding

Brian O'Hanlon, president of Open Blue Sea Farms, concedes that aquaculture doesn't have a spotless environmental record, but he cautions against judging an entire industry because of the transgressions of a few. "If you can imagine, not every farm does things the right way. Not every farm is in the right location. Not every farm is managed properly," O'Hanlon says. "So the problem is obviously that one bad apple can spoil the whole batch in a way."

O'Hanlon says his plans don't call for the use of antibiotics or genetically modified fish. He moved his aquaculture operation to the open ocean to space out his fish cages and create low-density farms, precluding the easy spread of diseases and the need for antibiotics. The appropriate scale also negates potential fish waste pollution, he says.

O'Hanlon says aquaculture is singled out for criticism over other forms of food production because fish farmers are using a public resource - the ocean - to farm their livestock. "It's tough for us. We're in public water. It's public domain. It's not like we're buying a piece of land and it's completely private and we do what we want on that piece of land. It's in plain sight and plain view for everybody to see," he says. "It's tough to say why fish farming gets so much negative attention, so much more than other forms of agriculture, which many would argue have much greater impact on the environment and our resources."

But the debate is evolving, O'Hanlon says. Some opposition groups "have really narrowed their focus to some of the key remaining issues, such as disease control, fish escapes, things like that," he says. "We obviously have different opinions on some other issues ... but I think at least we're really getting somewhere in terms of focusing on what matters."

Whit Richardson

Cage match

This composite image shows workers maintaining an installed AquaPod, above the water's surface and below. Divers in the AquaPod check on the health of the growing fish stock.

Steve Page, president of Ocean Farm Technologies, designed the AquaPod in a modular fashion so that each triangular panel can be retrofitted as needed, allowing the AquaPod to be custom designed for different uses. As the push for offshore aquaculture grows, new cage technology will be developed, but Page isn't worried. "Let the chips fall where they may," he says. "There will be many new designs, and OFT will be running like hell to stay ahead of the pack."

Reporter’s notebook

I drop into the warm water of the Caribbean Ocean, a tank strapped to my back, my hand on a regulator. It's far from the icy waters of Maine, so I've left the wetsuit at home. Accompanying Javier, a talkative diver who works at Open Blue Sea Farms in Panama, I slip through the hatch of the AquaPod and descend into the large spherical cage, where hundreds of cobia live out their lives until harvest. They've already been fed, so they're not interested in nipping at us.

We're in the cage to collect the "morts," the fish that died in the cage the previous day. And I was in Panama to report how this fish cage, which was made in Maine, was helping change the makeup of the aquaculture industry.

Last July, I was given the opportunity to travel to Panama and Mexico on a fellowship from the International Center for Journalists. My job? To report on offshore fish farming projects that are utilizing Maine-made technology to push the envelope in this emerging industry.

The center's World Affairs fellowship is designed to give journalists at small to mid-size news outlets - or those that lack a budget to pay foreign correspondents - the opportunity to report abroad on issues that have significance for local audiences. Aquaculture, which has a $130 million annual impact on Maine's economy and is in position to change our working waterfronts and the way people throughout the world think about the seafood they eat, is just such an issue for the readers of Mainebiz.

The reporting assignment marks - so far - the highlight of my journalism career. It has also enabled me to enter a new chapter in my life, as I depart Mainebiz after a four-year tenure to launch a freelance journalism career.

As important as the trip was to me, it was marked by some inauspicious beginnings. Early in my preparation for my trip abroad, I found myself scouring maps for the town of Puerto Lindo, Panama, which I had been told was home to one of the largest offshore fish farms in the world. But I couldn't find my destination on the map. I Googled it. Then I used Google Maps to zoom in on the Panamanian isthmus in search of it. But, to no avail. I was slated to visit a place judged so inconsequential that it wasn't even placed on a map.

If I was going to report on the aquaculture industry, and specifically how particular fish cages from Maine operate, another logistical consideration was my need to see them in action. The first thing Steve Page, president of Searsmont-based Ocean Farm Technologies, said after I told him I had received the fellowship was, "Do you dive?" I didn't. So I took a scuba diving course at the University of New England's pool in Biddeford, just in time to become certified before I set off for my trip.

I'm glad he asked. Otherwise, I would have missed out on one of the highlights of my reporting experience: swimming with the fish.

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments