Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

LURC reform draws scrutiny

A newly formed task force reforming Maine's Land Use Regulation Commission is drawing attention from environmentalists, developers and others, but one interested party has an especially big stake in the task force's work — to the tune of about 8.5 million acres.

That's how much land within LURC's jurisdiction falls under private ownership. Patrick Strauch, executive director of the Maine Forest Products Council, represents those interests, as well as those of sawmill operators, paper mills, biomass generators and others who earn a living from the working forest, which the National Association of State Foresters says contributes about $4 billion annually to Maine's gross state product.

"What we've seen from LURC is more of a focus on preserving that land as is and not having any consideration of the [forest's] role in economic development," says Strauch. "We think there needs to be a balance."

Strauch was one of five panelists convened by the Maine Real Estate and Development Association for a recent breakfast forum about the ongoing LURC debate. Bill Beardsley, the commissioner of Maine's Department of Conservation who chairs the task force, was in the audience. The differing opinions voiced at the breakfast likely foreshadow what will be a spirited discussion as the task force considers how to reform the agency that regulates use of more than 10 million acres of land.

LURC, established by statute in 1971, provides planning, zoning and permitting functions to more than 700 unorganized territories that lack municipal governments. The agency handles petitions as varied as a homeowner requesting permission to add a porch to the $33 million resort project proposed by developer Plum Creek that famously took five years to attain approval.

And that is part of the problem, according to Paul Underwood, an Aroostook County commissioner and president of the Maine County Commissioners Association. Underwood, a presenter on the panel, advocates for more local control, arguing some of LURC's authority should be turned over to counties to make their own determinations on smaller-scale petitions such as porch additions.

"The DEP should retain site permitting and forestry and agricultural issues should stay at the state level, but for smaller-scale projects, counties could be the municipal agent of planning," he said.

Delegating zoning and planning responsibilities to the counties while assigning permitting authority to DEP makes sense, according to Carlisle McLean, the senior natural resources policy adviser to Gov. Paul LePage, who supported a bill in the last session that would have dismantled LURC. It was the governor who proposed the task force, which met for the first time last month and will travel the state holding public hearings around LURC reforms. The task force is expected to report back to the Legislature's Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee in the next session.

But Orlando Delogu, a professor emeritus at the University of Maine School of Law who has been an open critic of LURC's regulatory reach, does not see county government as the panacea to the question of how best to regulate the state's unorganized territories. He notes counties are without the staff, resources and expertise to handle many of the projects proposed for the unorganized territories. He suggests an apolitical, full-time LURC board, modeled along the Maine Public Utilities Commission, should be formed to oversee existing LURC staff, who have experience and expertise and can take a holistic approach to land management that would be fractured under separate county control.

"I think the worst thing we could possibly do would be to jettison LURC's wilderness bias for a development bias," he said. "We need a balance."

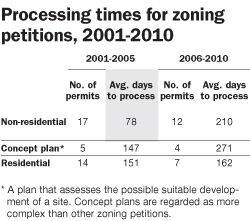

Delogu noted that most of the permits brought to LURC for review are approved, although the timeframe for those decisions can drag on "for months, or years, as some have done." With the exception of residential zoning petitions, the time to process permits for non-residential and concept-plan zoning permits has skyrocketed since 2005; non-residential permits nearly tripled to 210 days on average in 2010 while concept-plan permits nearly doubled to 271 days.

Rocky relationship

Strauch sees that pace as evidence of LURC's lack of accountability to anyone but itself and a challenge to landowners' rights. LURC, established 40 years ago, operates as as quasi-judicial body, without elected representation.

"Landowners are trying to preserve their land's value — that's an important concept," he says. "It's not about developing the land. The No. 1 priority is not losing value through regulation."

Strauch and the Maine Forest Products Council, which represents 350 members, spent four years working with LURC on Maine's comprehensive land-use plan. It was "not a very satisfactory experience," says Strauch. "The commissioners see the landowners as another special interest group," he says. "That's pretty intolerable."

He says there are several options to preserve Maine's scenic wilderness lands that don't involve a regulatory body. He cites conservation easements, which have protected more than 2 million acres from development while allowing working-forest activities, as an example.

"Conservation easements between a willing buyer and a willing seller is a really powerful thing," says Strauch. "They also recognize the landowners' value and a free-market right to be involved in decisions about their land."

This story was corrected to change Bill Beardsley's title from DEP commissioner to conservation commissioner. We regret the error.

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments