Historic preservation tax credit sparks development

By most accounts, the start of Maine's historic preservation tax credit program came at the best possible moment.

That moment was 2009, just after the collapse of the real estate market. "The timing was absolutely right," says Kevin Bunker, a partner with the Developers Collaborative in Portland. "There wasn't financing for anything else, but these projects could move forward."

The tax credit, piloted for a single project in 2005 and expanded statewide by the Legislature in 2008, piggybacks on an existing 20% federal tax credit for restoring buildings listed on the National Historic Register. The 25% state credit makes it financially feasible to develop historic buildings, especially in downtown districts, since it's significantly more expensive to rehab old buildings to meet modern building codes than build new. If affordable housing projects are included in a proposed development, the state credit increases to 30%. The tax credits made financing the rest of projects possible at a time when conventional lending was almost frozen.

"We're a smart growth firm anyway — it's what we like to do — but the credit made it possible to move forward when we wouldn't have been able to otherwise," says Bunker.

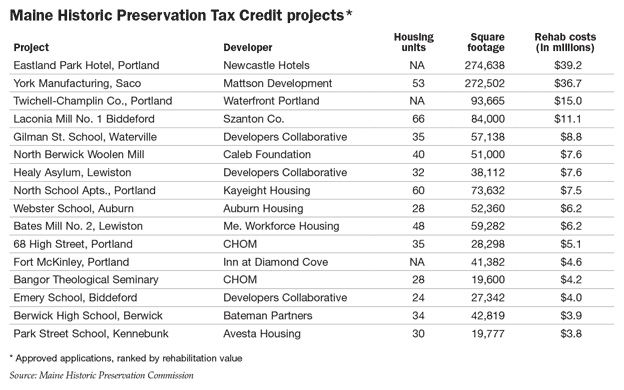

Since 2009, Bunker has overseen three projects that were completed using the tax credit: the Gilman School in Waterville; Healy Asylum in Lewiston; and the Emery School in Biddeford. His firm is about to begin construction on an overhaul of office space at the Lamb Block in Livermore Falls, and has applied for approval of work at Hyancinth Place/Walker Green in Westbrook. The first three projects totaled $20.4 million in rehabilitation costs — the portion of construction costs eligible for the tax credits — and created 91 units of affordable housing. The Livermore Falls office block conversion will cost $2 million for rehab.

In all, 59 projects have been approved for credits by the State Historic Preservation Commission, which oversees the program. Through the end of 2011, 55 applications had been approved, with 20 completed and 35 in progress. In all, the 55 projects will create 422 units of affordable housing and 584 units overall, including market rate units. Another 131 units of affordable housing will be preserved.

Construction figures are also impressive, given the depressed market: $219.5 million for renovated space, and another $46 million for new construction. In all, more than 2 million square feet of renovated space will be added to Maine's stock of housing and commercial space.

Not surprisingly, the largest number of projects — 18 — are in Portland, but there have been developments in just about every 19th-century downtown, including smaller ones such as Berwick, Dover-Foxcroft, Gardiner, Hallowell, Eastport, Freedom, Kennebunk, Norway, Ogunquit, Livermore Falls and Rockport.

Mike Johnson, tax incentives coordinator for Maine Historic Preservation, says the program seems to be meeting expectations, and legislators are keenly interested in the results and supportive of the program even though the state is foregoing tax dollars. He says Maine has taken into account the experience of other states in crafting its program.

Because there's a $5 million cap on construction expenses and the credit is refundable over four years, the state avoids the kind of revenue surges that tend to attract attention, he says. "Some states are more generous, others less so, but this one has been carefully crafted to work for Maine," he says.

Bunker emphasizes the user-friendly qualities of the program, which he says is a lot simpler than some other incentives.

"You try to understand the federal affordable housing rules, and it's like you're doing brain surgery," he says. "This one is a lot easier to digest."

A wobbly start

Ironically, the very first project approved for a historic preservation credit, the Kennebec Arsenal in Augusta, remains vacant with no immediate prospect for reconstruction. Under terms of 2006 legislation, the state conveyed the property to North Carolina developer Tom Niemann for $1, with the expectation that a mixed-used development, with some new construction and possibly a marina on the Kennebec River would result. So far, nothing has.

Niemann announced one project in 2007, then a scaled-down effort in 2009 and little has been heard from him since.

The state is now attempting to repossess the property, and the Bureau of General Services has referred the matter to the Maine Attorney General's Office. Augusta City Manager Bill Bridgeo acknowledges some frustration that nothing has happened to the highly visible property for six years; in the meantime there have been two arson fires and continued deterioration of the structures.

Yet he doesn't think the failure of the Arsenal project to date means that the state program is flawed. "This is a proven way to rebuild downtowns and bring back development where cities most need it," Bridgeo says. He added that federal tax credits were vital to redeveloping the old city hall, and hopes the Flatiron Building — the old Cony High School — may someday be redeveloped through the state program.

Things went somewhat better in 2007, when another piece of legislation led to renovation of the Lockwood Mill in Waterville, once the headquarters of the Hathaway Shirt Co. For that venture, Niemann partnered with Rhode Island developer Paul Boghossian, a Colby College alumnus, in a project that opened in 2009. Housing is nearly fully occupied, says Boghossian, while office space is 65% rented, and retail has lagged. Overall, 60% of the five renovated floors are rented.

The partnership itself, however, has soured. Boghossian says Niemann reneged on commitments to maintain and raise capital for two adjacent mill buildings, leading to expensive repairs when frozen sprinkler pipes burst. Boghossian has since completed foreclosure proceedings against the partnership — "even though it's like I'm filing against myself" — and says he expects to buy back the two buildings when the foreclosure auction is scheduled.

At that point, renovations can begin. "I'm bullish on this project," he says. "There are tenants lining up, the economy is improving, and a lot of people want to live downtown."

Niemann could not be reached for comment.

Boghossian has experience with the Rhode Island historic tax credit program, which was discontinued by that state's Legislature in 2009 amid a major budget crisis. He says the state was over-extended and needed to cut back, but he still questions the choices the politicians made.

"They kept the film tax credit but got rid of the one for historic preservation," he says, questioning the rationale. "The historic program creates lots of local jobs because it's labor intensive. And you're not going to bring in masons and electricians from out-of-state." Rehabilitation is better for a state's economy "than subsidizing a Hollywood actor's salary," he says.

Measuring results

As it happens, the tax impact of the Maine program was scrutinized last year in a report from Planning Decisions commissioned by Maine Preservation.

Frank O'Hara, a principal with Planning Decisions, says the effect on taxes and revenue is complex. Increased property values and new jobs have to be factored in as well as the potential revenue loss by the state, although, as he points out, "These properties usually aren't producing any revenue at all now, since most of them are vacant."

O'Hara say there's a three-part pattern concerning tax revenues. "In the first years, the effect was positive, because there are construction jobs and taxes haven't come due yet." Then there's a five-year period in which net revenue, in fact, decreases as credits are paid out. But, long term, the overall economic boost caused by the projects turns the numbers positive again, O'Hara says.

While the program remains attractive to developers, one component might become less prominent, thanks to new management decisions at the Maine State Housing Authority. State Treasurer Bruce Poliquin and board chair Peter Anastos have advocated for new rules that will remove affordable housing subsidies from projects such as those the Developers Collaborative undertook in Lewiston, Biddeford and Waterville. Poliquin and Anastos made much of what they calculated as the costs per unit, and said housing could be built for less.

Bunker of Developers Collaborative says he thinks the criticism is unfair because it doesn't accurately reflect the purposes of the various programs involved. "Government, state and local, has set a long-term priority of restoring historic buildings, and some old buildings — particularly schools and churches — lend themselves to housing." He says that, "once you net out the various factors, the costs aren't excessive." The federal credit, he says "has been in effect since 1976. This is still a priority."

But Bunker says there are still numerous historic buildings that are underutilized and potentially good sites for renovations.

That doesn't mean that all of them are, he says. "Sometimes, people look at an old building and say, 'It's beautiful. You've got to save it.' But it doesn't work unless you have an end user who's able to carry the mortgage and pay taxes."

Bunker says there are four major factors behind successful restorations:

- A tenant ready to relocate and move in;

- A seller who's realistic about the value of the building – "most of them aren't worth $1 million," he says;

- Whether a renovation will add substantial value to the building, in excess of reconstruction costs;

- And finally, the availability of federal and state credits. "It makes the difference, often, between a project where the numbers work, and where they don't."

For the foreseeable future — the credit is authorized through 2023 — Bunker sees no shortage of opportunities to bring old buildings back to life.

Kevin Mattson, whose firm, Mattson Development, specializes in commercial redevelopment, agrees that the tax credit is make-or-break when it comes to historic downtown buildings. "There isn't a single project on the list that would have been built in that form without the tax credit," he says.

Mattson, for several years now, has been converting the buildings on Saco Island once used by York Manufacturing, and the projects won't be going anywhere without the credit. So far, a building containing offices and a popular brew pub has been restored. For some of the larger mill building, "this is a multi-year venture, to say the least."

Current legislation has the tax credit expiring in 2023, when lawmakers will presumably review it again. Says Mattson, "If you want to bring these buildings back, the credit has to be there. Otherwise, it won't happen."

Read more

Comments