Radon, uranium testing spikes with surge in home sales

For Portland native Kate McCabe, moving from a home hooked into the public water system to one with a private well was as much about having safe drinking water as it was about expanding the space for her growing family. So when the inspector for the house she and her husband planned to buy in North Yarmouth recommended thorough testing of the air and water, McCabe, who has a 2-year-old and another baby on the way, readily agreed. And she's glad she did. The test results showed extremely high air and water radon and water uranium readings, and she almost backed out of the deal.

“I tried to talk to as many people as I could as fast as I could,” says McCabe, 35. “I called at least 10 different companies.” She decided to negotiate with the sellers to pay for air and water mitigation systems, and after they agreed to pay the nearly $18,000 expense, she agreed to the sale and plans to move in toward the end of September, after the systems are installed.

“For weeks I thought of walking away,” she admits. “It's a big deal to me to have unsafe water. I was shocked that I had uranium. But North Yarmouth as a whole has uranium, so this issue would have come into play no matter where we went. It's a product of the areas we were looking to move to.” Uranium is not part of the standard water test done on homes.

McCabe is not alone in her concern for a healthy home. Other buyers and sellers, real estate professionals, home inspectors, testing labs, mitigation equipment companies and even legislators are becoming aware of the prevalence of radon gas, water radon and more recently, uranium in the water in Maine. Requests for tests and mitigation devices are increasing at a brisk pace, sparked to some degree by the economic recovery, and specifically the spike in the real estate market, and a new regulation taking effect in March 2014 requiring radon air testing in rental housing. Tests are not now required in real estate transactions in the state, though there are some residential property disclosures required if owners know about problems.

Close to half of Maine's population gets its drinking water from private wells, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, which notes that few of them are tested routinely compared to public water supplies, which are tested monthly and every year. A 2011 Maine Geological Survey report found that fewer than 40% of private wells are tested for uranium, even though statewide more than 5% of wells have high uranium levels and 33% have high radon. Towns in the state with the highest concentrations of uranium include Durham, Naples, Sebago, Falmouth, Swanville and Bar Harbor. Tests run from $30 to $120, depending on what is being tested.

“At times when the real estate market is booming, more testing is done,” says Mike Gelberg, president of Air & Water Quality Inc. of Freeport and Ellsworth, which has installed 15,000 water treatment and mitigation systems, including those in McCabe's new home. Sales of single-family existing homes in Maine rose 31% in July over the previous year, according to Maine Listings, almost double the national rate of 16%.

Beau Mears, president and CEO of Northeast Laboratory Services in Winslow, says his company's Portland office is seeing an increase in street traffic at its Forest Avenue location, where people can walk in and pick up the tests.

“I sell about $300,000 to $400,000 per year of water and radon tests,” he says, though air radon tests are done about four times as often as water radon. “People are far more conscious about air quality than they were before. Water testing is stronger than ever.”

“No one wants these kinds of issues upsetting the sale of a property,” adds Gary Vogel, an attorney with Drummond Woodsum & MacMahon in Portland and chair of the Maine Real Estate & Development Association's legislative committee. He adds that the burden is on the buyer to check for any problems. That, in turn, is keeping inspectors busy.

“If our inspector hadn't mentioned it, I'm not sure we would have known,” says McCabe. “The only thing I'd recommend is be an informed buyer. Go to the state website. Ultimately your decision to [go with] a house could possibly put your health at risk.”

In the ground

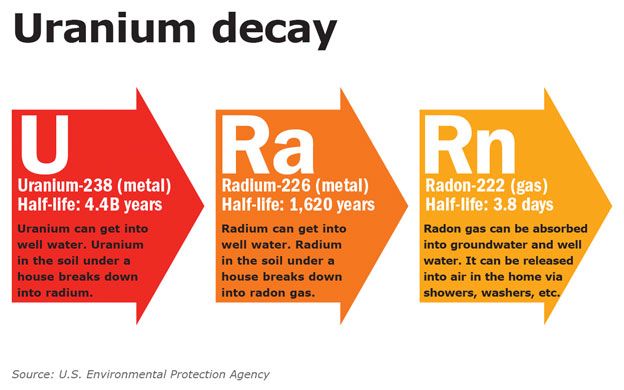

Because of Maine's geological formations, uranium and one of its breakdown byproducts, radon, are more common in the rocks and soils here than in many other states. Neither is detectable by smell, taste or color in the water or air. Air radon, which enters a home through dirt floors or cracks and pores in concrete walls or floors, has been proven to cause lung cancer, according to the state's Department of Health and Human Services. It is the second leading cause of lung cancer overall and the leading cause for people who don't smoke.

Radon in the water isn't dangerous to drink, but it is released inside a building after showers and other water use and then becomes a health risk. And uranium in drinking water has been linked to kidney disease. In both cases, it can take years of exposure to get sick. An estimated one in three Maine homes has elevated air radon, and an estimated one-third to one-half has elevated uranium in well water. City water is tested regularly, so private testing for radon and uranium by home buyers and owners is less frequent.

Despite the prevalence of such radioactive substances in the ground and in well water, testing for uranium, in particular, has lagged, partly because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set a standard measurement for uranium in water around 2003, and because there is no law requiring testing for it. Radon testing has been done since the 1980s, ever since a nuclear power plant engineer in the Reading Prong area of Pennsylvania set off radiation detectors as he went into the plant, and it was discovered that certain areas, especially in the Northeast United States, had pockets of heavy radon.

Similarly, a 2012 U.S. Geological Survey report that found arsenic levels in bedrock water in eastern Maine occurring at three times the national average sparked a rise in arsenic testing; it now is typically included in the standard water test for homes. That same study found an unusually high uranium concentration in areas such as Sebago Lake, but testing for uranium still requires a separate water test and it is not done as a standard test. Even bottled water producers like Poland Spring test and treat their water.

“Poland Spring water doesn't come out of the ground and go into the bottle,” says Gelberg of Air & Water Quality Inc.

“With arsenic, uranium and radon, you don't smell, taste or see the ramifications,” says Gelberg. “But Maine has some of the highest levels of them in the country. Thousands of homes in Maine are not tested for uranium, and I guarantee thousands of homes have it. If it smelled, people would test for it right away. And you don't get sick from it right away. It still isn't well publicized.”

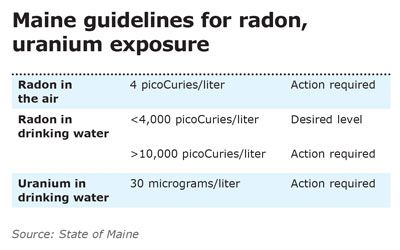

In McCabe's case, her home inspector was aware of the problem in her area, and recommended the tests. The state of Maine recommends action if radon in drinking water tops 10,000 picoCuries per liter, if air radon is 4 picoCuries per liter or higher and if drinking water uranium is 30 micrograms per liter or more. In McCabe's case, her radon water was more than double the maximum level at 24,000 picoCuries per liter, the air radon was more than double at 9.5 picoCuries per liter and the water uranium was more than 32 times the maximum at 970 micrograms per liter.

“I talked to the state toxicologist and she asked me if I was living in the house,” says McCabe, who wasn't at the time. “She said if I was, I needed to call my doctor.”

After extensive research on her options, McCabe became comfortable tossing around terminology like reverse osmosis and ion exchange. She opted for a radon system that cost $1,500, a double water softener for $3,000, a radon water mitigation system for $5,200 and a whole-house reverse osmosis system for the uranium at $8,200. The seller agreed to pay for all of it.

Bart Stevens, president of the Maine Association of Realtors and broker/owner of Century 21 Nason Realty in Winslow, says he hasn't seen an uptick in requests for uranium tests, but it's a relatively new issue.

“Ten years ago, people never talked about arsenic,” he says.

The association has a list of 23 tests a homeowner should consider in its standard purchase and sale agreement form, including arsenic and radon in the air and water, though he adds the association sends people to experts in the field to handle any issues.

One issue with testing, says Gelberg, is that people don't want to necessarily tell their neighbors there is a problem, partly because it might make their home look defective and partly because health issues don't seem to be a priority.

“Health concerns are not top of the list in Maine,” he says. “[A mitigation system] is not an easy product to sell if there is not a monetary reason or it isn't required.”

Ironically, he adds, homes that have mitigation systems might be safer than others in the neighborhood that don't.

While some neighborhoods, like McCabe's, have a widespread problem, it's also possible for side-by-side homes to have dramatically different readings, one within normal range and one with high levels of uranium or radon. And while not everyone can afford the inspections, series of tests and mitigation systems, they should at least turn to bottled water if they find a problem, experts agree. Says Gelberg, “The first step is to limit your exposure.”

Radon on the radar

The new rental housing radon testing requirements, Public Law 157 (LD 1048), and Public Law 278 (LD 943), which aims to reduce lung cancer rates in Maine, require landlords to have their residential buildings tested for radon effective March 1, 2014. Inspectors like Reese Perkins, owner of Perkins Home Services in Bangor, expect the new law to drive up radon testing demand.

“It's huge,” says Perkins. “There are 9,600 rental units in the city of Bangor, and while all won't need to be tested, there could be two tests per building in a six-unit building.” He charges $125 for an air radon test.

He expects legislators to keep moving in stages to improve the safety of buildings, and he says the next step is probably elementary schools.

Comments