Should Maine be smug about smog?

Maine environmentalists say the state already is well positioned to meet the first national carbon emission limits, proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in early June, but upon further examination by local regulators and companies, there is some devil in the plan's details that could prove to be a headache, or at least a source of confusion, to those preparing to comply.

“I've been at the DEP 28 years doing air work, and this is one of the most complex integrated compliance rules [I've seen],” says Marc Cone, director of the Maine Department of Environmental Protection's Bureau of Air Quality. “It's going to take some time [to get through it]. There are a lot of resources being devoted to it, and a lot of people are scratching their heads.”

DEP has five people assigned to read through the hulking, 645-page EPA Clean Power Plan plus its myriad of associated technical documents, and the Maine Public Utilities Commission has about an equal amount of staff sifting through it. The governor's office also is expected to issue comments on the Clean Power Plan. They all must compare it with guidelines in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a nine-state collaborative that includes Maine, and the EPA's own boiler impact rules, which changed two years ago.

The EPA's Clean Power Plan aims to reduce carbon pollution from the power sector by 30% nationally and by about 14% in Maine by 2030. Maine plans to use RGGI to meet the new proposal. Carbon pollution from power plants has fallen 40% since 2008 and RGGI has generated more than $30 million for energy efficiency investments in Maine.

The plan clearly is a priority for the Obama administration, which makes it high priority for Maine as well. “It is one of the biggest issues for the next couple years, period,” says David Littell, a commissioner at Maine's PUC. “It's big nationally and internationally. The rules will be one of the elements of the 2015 Climate Conference in Paris.” Littell adds that it still is not clear whether the Clean Power Act, if passed, will be a rule that is legally binding or a guideline, which is more flexible.

Still, the PUC, DEP and industry already are meeting to try to understand the EPA proposal and to check that there are no unintended negative impacts on the state, Littell says. He and Cone say some aspects of RGGI and the EPA's boiler and Clean Power Plan already appear to be in conflict or need clarification. Among those are the applicable boiler size, how biomass start-up fuel is handled and rate- versus mass-based measurements of the different groups.

“The rules are not consistent and this is worrisome,” says Russ Drechsel, general manager of the UPM Madison paper mill, which in April took its first delivery from the new Kennebec Valley natural gas pipeline constructed by Summit Natural Gas of Maine. Natural gas burns cleaner and typically is less expensive than No. 6 fuel oil. Two other Maine paper mills, Sappi Fine Paper's Somerset mill in Skowhegan and Huhtamaki Inc. in Fairfield and Waterville also are anchor customers for the $350 million, 68-mile pipeline from Augusta to Madison. UPM Madison already is switching over its two dual oil and natural gas burners to run only natural gas, and plans to also convert an idle third boiler to dual fuel and fire it up with natural gas this year, Drechsel says.

While UPM Madison currently does not use biomass, it might one day consider it, and at that point its plant may fall under the Clean Power Plan, if it is adopted in its current form. “The vast majority of biomass boilers need natural gas to start the fire, and they will be regulated under the new rules, but there are different rules under RGGI, which generally exempts biomass,” he says.

“We need to look at the boiler and biomass [issues],” Littell agrees. He says the Clean Power Act gives some guidance on the affected energy generating units, known as EGUs, in Section 60.5795. That section identifies EGUs with a baseload of 250 million British thermal units per hour of heat input of fossil fuel, either alone or combined with another fuel, that were built to supply one third or more of their potential electric output to the grid over a three-year average for gas and one year for steam.

“There is no explicit allowance for co-firing another fuel [and not coming under the new guidelines],” Littell explains. Under RGGI, multi-fuel boilers are covered if 50% or more of their output comes from fossil fuels with existing units and 5% with new units, or if they are generating electricity for themselves rather than for the grid.

Another concern Littell is finding as he talks to mills is that they are worried about how their pollutant emissions are going to be assessed, he says, because the EPA guidelines will be rate-based, whereas RGGI is a cap-and-trade program so it is mass-based. Littell adds that his group is spending a lot of time looking at the formula to translate the two measurements.

“The problem is, we haven't looked at all the details,” adds Cone. “There are definitions that would seem to be contradictory in the rate. There are parts we would want to comment on.” He adds that he can't tally the total costs to comply with the plan nor all the implications for Maine until the state comes up with comments, runs them by the EPA, the final rule emerges and the state submits its plan to conform.

A helping hand

The EPA seems to be aware of the confusion, having scheduled four conference calls and three webinars with U.S. states the last week of June alone. States have until mid-September to comment on the plan. President Barack Obama has asked the EPA to make the rules final in June 2015, after which the state would have at least a year to submit its plan to achieve the reductions through RGGI, also known as “Reggie.”

RGGI is a mandatory greenhouse gas pollution reduction program for CO2 emissions from the power sector. It comprises CO2 budget trading programs in its nine state members and creates a regional market to buy and sell CO2 allowances. Efficiency Maine administers the program in the state, offering 50% toward efficiency projects.

Local environmentalists tout RGGI as a major contributor to Maine's dramatic improvement in CO2 emission decreases, but others say the shift to natural gas to save energy costs at mills and other factories made the major contribution, though RGGI helped those companies afford energy improvements that otherwise would have had too long a payback to consider.

One example is Twin Rivers Paper, which operates a paper mill in Madawaska. Since 2006, the mill says it reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 76% and now gets 83% of its energy from carbon-neutral sources. Among the four projects with RGGI funding, the mill put in 37 variable frequency drives costing $601,000, half provided by Efficiency Maine, says David Critchfield, an operating partner with Atlas Holdings LLC, one of the owners of Twin Rivers. “A variable frequency drive is a motor, so the electricity bill drops and the CO2 drops,” with more efficient drives, he says.

Critchfield says every mill has a backlog of projects, but with tight operating margins, proposals with a payback of 3 years or longer often sit on the back burner. “The 50% matching grant fund from RGGI stimulated projects,” he says, adding that the mill has 172 efficiency projects that have the longer paybacks, but that now may start moving forward. “A three to four year payback now is one-and-one-half to two years with RGGI,” he adds.

Drechsel of UPM Madison agrees, having taken advantage of RGGI funds for four projects. One, a lighting project, cost a total of $48,891, with a projected savings of $24,212 a year, which represents a payback of one-and-one-third years. And a $161,891 air compressor project is saving the mill $68,419 a year, with a similar payback period.

In addition, Efficiency Maine contributed $130,000, or half the cost, of a project to separate good fibers from contaminants using a screening device, which saved the plant 900 megawatt hours a year, or about $54,000 annually at $60 per megawatt. It also got $133,000 from Efficiency Maine to replace pulp tank agitators with more modern ones, which saved it 1,150 megawatt hours a year, or about $69,000 annually.

“RGGI made the funding available to decrease energy demand and CO2 emissions, and they accomplished that,” Drechsel says. “These projects would not have passed our corporate hurdles with the payback. But overall, they decreased our energy consumption.”

However, because of rising energy costs, he says his company has paid more for electricity cost increases than the RGGI funds it received from Efficiency Maine. “We'll probably come out about even.”

Drechsel estimates that the cost to convert all three of his boilers to dual fuel was about $1 million. When all three boilers are running natural gas later this year, his sulfur dioxide emissions will fall dramatically to 200 pounds per megawatt hour when burning natural gas from 1.2 million pounds when burning oil. And he expects to cut CO2 emissions by one-third from 2010, when the boilers burned only oil.

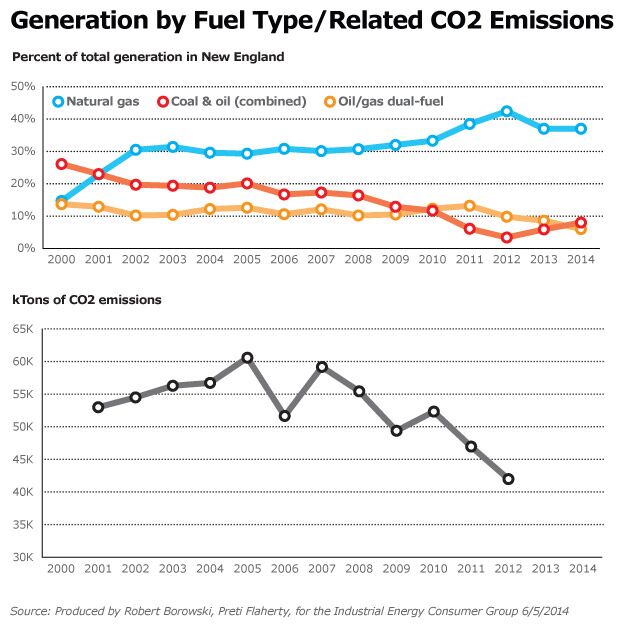

While he says he supports RGGI, “The overall greenhouse gas reductions in New England aren't as much by RGGI as by conversion to natural gas and elimination of coal. The driving force was shutting down the old coal-fired plants over the last five to 10 years.”

Maine no longer has any self-standing, coal-fired plants. However, Cone says SD Warren Sappi Westbrook has a multi-fuel unit that fires coal and has averaged 9% of its total energy input from all fuels combined over the last two years. Coal represents nearly all the fossil fuel used at the plant. And Rumford Paper Co. has two multi-fuel units that fire coal at approximately 11% of the total energy input from all fuels combined. Coal represents nearly all of the fossil fuel use in these two units as well, he says.

However, those units currently are not covered under RGGI because their fossil fuel rate is so low, Cone says. They also were not cited in EPA documents as affected units. “But some of EPA definitions are confusing, so we will need certainty going forward and paying particular attention to the details in the proposed rule,” he adds.

Pipeline constraints

More worrisome to Drechsel and others are constraints on the natural gas pipeline, which won't see much capacity added until at least 2017.

However, 2 billion cubic feet of new natural gas pipeline capacity is needed now to tame the energy cost spikes and bring New England in line with other states, according to a study commissioned earlier this year by the Industrial Energy Consumer Group, which represents large industrial facilities in the region.

“We definitely need to have a larger natural gas transmission line,” says Drechsel. “It is a crisis.”

He pointed to a report from ISO New England, which manages regional electricity demand in New England, which showed that for the first time in the last decade electricity prices topped $50 per megawatt hour compared to the typical $30. Peak prices hit $1,000 per megawatt hour during last December's storm.

“We had to reduce production this winter due to high energy prices,” he said, though he wouldn't comment on how much.

Verso Paper, which declined to talk to Mainebiz because it is in a quiet period as the Department of Justice reviews its acquisition of NewPage, did note in a transcript of its first quarter 2014 earnings call on May 7 that it had 38,000 tons of downtimes during the quarter at its facilities in Maine. The downtime was driven by a combination of weak demand and the huge spike in natural gas prices in the first quarter of the year. Transportation costs for fuel also remain a drag on revenue.

To hedge against price spikes and other negative impacts, mills have been trying to generate more of their own electricity, says Critchfield.

Drechsel, who began the switch to natural gas by first moving to compressed to liquefied and finally to pipeline natural gas, still is keeping one foot in the world of oil. With concerns over fluctuating fuel prices and potential disruptions to the under-capacity pipeline, he can switch his boilers from natural gas back to oil in a few hours.

Says Drechsel, “If the natural gas pipeline goes down for repairs or if someone hits a line in their yard, we want to be able to keep operations going.”

Read more

The wind industry's relative youth means fewer traditional barriers for women in Maine

Comments