Going Downtown: Redevelopment projects aim to put the 'cool' back into Maine's downtowns

The lights dimmed across many formerly thriving downtowns in the 1970s, an era known internationally for its economic upheavals and a time when city dwellers fled to the space and greenery of the suburbs on new superhighways near proliferating big box stores.

This “hollowing out” phenomenon referred as much to the lost sense of community as to the lack of people strolling down sidewalks with shopping bags. Stores closed, empty buildings decayed and many downtowns became mere thoroughfares rather than destinations.

The trend is starting to reverse, buoyed by local, state and federal programs offering know-how and helping with private and public fund-raising to restore or repurpose empty or neglected buildings. In places like Norway, Gardiner and Waterville, many of those buildings are historic and could be tourist attractions.

“It's a response to the 1970s sprawl that drove things to the suburbs,” says Jennifer Olsen, executive director of Waterville Main Street, a program that sprung from the National Main Street Center, a subsidiary of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. In Maine, it runs under the Maine Development Foundation. Olsen also has worked on redevelopment projects in Millinocket and Skowhegan.

The revitalization movement runs across all economic classes and ages. It aims to attract retirees into towns, to keep young people from leaving and to bring people Mainers who moved away.

One of the more pervasive movements is the National Main Street Center, which started in 1980. Its organizing framework is used in more than 2,200 communities in 44 states. There are 10 Main Street Maine communities, each registered as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and with a paid officer like Olsen. There also are affiliate or “network” members without full-time staff.

The Main Street plan has four approaches: organization, promotion, design and economic restructuring. That includes adding attractive street signs and holding events, like the Swine & Stein Oktoberfest in Gardiner, explains Lorain Francis, senior program director and state coordinator for the National Main Street Center.

“That festival gets people into the community,” she says. “It's a measure of economic development.” She adds that in 2016 the Main Street movement will start to measure and track economic development such as the total amount of physical structures that were improved and the net gain in jobs.

Mainebiz recently visited three towns in the midst of redevelopment — Norway, Gardiner and Waterville — to explore their revitalization efforts. Gardiner and Waterville are Main Street Maine communities and Norway is in the network.

We found commonalities such as buildings in disrepair with absentee landlords, historic buildings in need of money for a facelift, complaints about parking and the like.

But we also found new businesses, like the Norway brewery and restaurant in the works by a young couple who returned to the town (from the country of Norway) to raise a family and help economic development; a co-op manager and a craft beer purveyor in Gardiner who each fell in love with the town's old buildings and moved there to make an impact; and two young sisters who started a pole exercise studio on Waterville's Main Street because they love the area and want to see it grow.

Norway

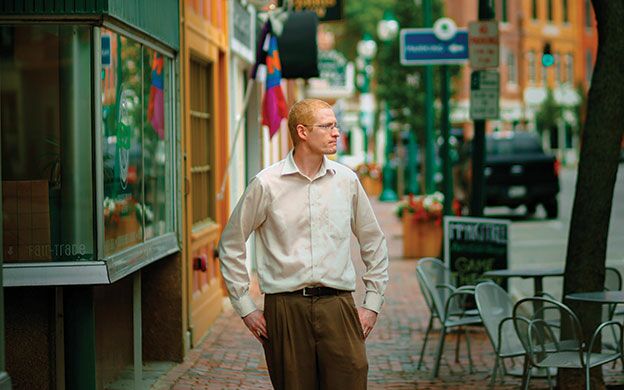

When Charles and Erika Melhus returned from Stavanger, Norway, to Norway, Maine, last December, they dreamed of creating their own brewery and beer garden and raising their family in the town where Charles was raised.

Charles, 32, studied brewing in his father's home country. Erika, 29, graduated from the Maine College of Art with a focus on furniture design.

They looked at several empty buildings in downtown Norway and decided on The Norway Trolley House, which most recently was a restaurant but originally was a trolley house. Melhus's mother and father bought the property, which the young couple is now rehabbing into Norway Brewing Co., which is scheduled to open later this fall, with an outside beer garden planned for next summer.

The couple raised $12,000 from crowdfunding, and family put in another $100,000. Melhus says the total investment comes to about $370,000 including the $170,000 his parents paid for the building. They're also working with Norway Savings to roll a short-term equipment loan into a long-term loan package.

He's also had guidance and advice from SCORE and the Maine Brewers' Guild, and credits Town Manager David Holt, Norway's select board and others for being open to new ideas.

“This is a great family environment. We came here to build up the community,” says Melhus. “Norway is on the cusp of being the cultural and economic hub of Oxford Hills.”

Melhus plans to brew his own craft beers using local ingredients, including hops from a grower in nearby Harrison. He also plans to name the beers after local establishments like Green Machine, a bicycle shop up the street.

Andrea Burns, president of Norway Downtown, a nonprofit community group working to revitalize Norway, adds that one of the larger projects underway is a new outpatient clinic that she says could bring 800 people into the area for services.

Western Maine Health Care Corp., a Norway-based MaineHealth affiliate, said last fall that its $10 million expansion is part of its push to increase outpatient care services. Plans call for constructing an $8.2 million, 25,000-square-foot building on Pikes Hill Road where doctors' offices from other locations will merge. Western Maine Health is expected to break ground on the project next spring.

Meantime, Burns and others are looking to more rehabilitation projects, like the second floor of the Norway Opera House. The first floor of the former entertainment center now houses new businesses including leather store Rough & Tumble, yarn and wine shop Fiber & Vine and gem store The Raven Collections.

Upstairs, however, it remains empty, as do many second floors of downtown Maine stores. A fundraiser to renovate the Opera House's second floor was well on the way to its $9,000 goal following a dance and music festival in late August in the streets of Norway.

Second floors have been the bane of small downtowns. But Scott Berk, owner of Cafe Nomad and part owner of Fiber & Vine, fixed up two apartments above his cafe, and once the current tenants move out he says he may turn the spaces into Airbnb rooms.

Berk, who still works as a graphics litigation consultant, says he wanted to run a cafe since college as well as renovate a building, and Maine was an affordable location.

“The cost of failure isn't nearly as high,” he says of Maine after moving here from Boston. “I found this cute, very dilapidated building on Main Street. He opened the café in August 2007 and revenue has grown 15% annually every year since.

“If you create a nice space in what was an empty storefront, people will want to come there,” he says. “In the last year-and-a-half I'm seeing people walking up the street with shopping bags in their hands.”

Maine Preservation, a nonprofit, statewide historic preservation group, said in August that it would assist in the transition and sale of three historic downtown buildings, including L.M. Longley & Son on Main Street, a hardware store that is now for sale as its owner wants to retire, and the 100 Aker Wood Frame Shop at 413 Main St.

Nancy Smith, executive director of GrowSmart Maine in Portland, says the passage of LD 1372 in the last session of the Legislature was a clear win for the redevelopment of upper floors in Maine downtowns. “The bill incorporates language around considering the barriers to redevelopment of upper floors into municipal comprehensive plans,” she notes.

Gardiner

Unlike Norway, which gained population in the 2000 and 2010 U.S. Census figures, Gardiner's population has been on the decline, and that's something the town wants to rectify.

“It is a concern,” says Patrick Wright, director of Gardiner Main Street and economic development coordinator for the city of Gardiner. “You need people for downtown economic development. We believe a vibrant community will stem that loss.”

He and other economic development officials have worked hard to attract businesses, especially chains with successful track records like Frosty's Donuts, a Brunswick-based chain that opened its fourth location in the state in Gardiner in July of 2014. Wright reached out to the owners with a $25,000 forgivable loan and grant package from the Gardiner Growth Initiative, a collaboration between Gardiner Main Street, the Bank of Maine, the Gardiner Board of Trade and the city.

“We are looking for businesses that have been successful in other parts of the state like Frosty's,” he says, as opposed to inexperienced startups that are more likely to fail.

Gardiner's incentive programs attracted its newest store, a franchise of Craft Beer Cellars, which has 16 locations existing or in the works, including one in Portland.

John Callinan, who still is finishing the insides of the store, which is a few shops down from Frosty's, said the five-year Gardiner Growth Initiative forgivable loan of $35,000 and the $10,000 grant from the Gardiner Board of Trade were key to his decision to invest in Gardiner.

“However, not to be underestimated was the welcoming attitude extended by the local business community as well as by the elected and appointed officials of the city,” says Callinan, who formerly worked in the health care industry. “These qualities convinced me that Gardiner as a whole is very serious about making it a community where people of all age groups will find to be a desirable place to live and to visit.”

The building cost $115,000 and will take another $65,000 to $75,000 to renovate, not including initial inventory or other start-up costs, nor the cost to renovate the second story into an affordable living space, he says.

The only drawback is that like other cities along the Kennebec River that are in Federal Emergency Management Agency flood plains, flood insurance is pricey on top of regular business insurance.

To try to decrease his $4,000 annual flood insurance fee, Callinan has hired a surveyor to get a certificate of elevation.

Eric Dyer, general manager of the Gardiner Food Co-op & Café, had a similar positive reaction to Gardiner as Callinan. A former municipal government worker on the Cranberry Isles and Chebeague Island, he found the career change he wanted in Gardiner, where the new co-op opened on May 31.

In April, the co-op was awarded a $90,000 Community Development Block Grant to create new jobs when it opened its storefront. CDBGs are run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and administered by the Maine Department of Economic and Community Development.

In June, the city of Gardiner said it was receiving $300,000 in a CDBG to help Lost Orchard Brewing Co., which makes hard apple cider, to buy equipment and inventory and acquire working capital. The funds are being matched by $444,000 from the company and will create 10 jobs.

Also, the city is receiving $540,000 to help Central Maine Meats LLC buy equipment and inventory and acquire working capital. The funds are being matched by $960,000 from the company, which aims to create 18 jobs.

With the mix of craft breweries, a food co-op and various eateries, Dyer says, “We want to be a successful as Portland, but in our own way.”

Another draw to the city is its historic buildings, namely Johnson Hall Performing Arts Center, whose upper floor needs to be renovated, says Melissa Lindley, program coordinator of Gardiner Main Street.

Strolling the streets of downtown, she also points to a series of historical posters mounted in store windows, which next year will become part of a historic walking trail.

Waterville

Waterville, which has the advantage of pulling in students from Colby College, Thomas College and Kennebec Valley Community College, has made news lately due to moves by Colby College. That college in late July bought the Old Hains Building and Levine's clothing store building downtown, and plans to buy a third, at 16-20 Main St., to help revitalize Waterville.

The college reportedly will use the buildings for housing and retail stores.

Some large investments have brought high-class entertainment and tourism to Waterville. Colby College Art Museum's $15 million Alfond-Lunder Family Pavilion opened in 2013 with a world-class collection of art. The Waterville Opera House completed a $5 million renovation in 2012. The Waterville Public Library underwent a $3 million expansion, and the Maine Film Center bought the Railroad Square Cinema in December 2012 to create a permanent home for the 10-day Maine International Film Festival.

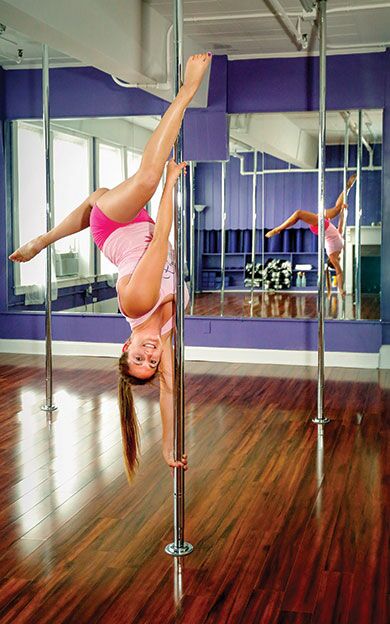

The city also recently held the 23rd Taste of Waterville, a festival about food, says Kimberly Lindlof, president and CEO of the Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce in Waterville. Activities like that, and new businesses like Empower Body & Pole Fitness, are energizing the town, she notes.

Take Heather MacKenzie, 25, and her sister Kate Poulin, 28, who grew up in nearby Winslow. With all the new activities on Main Street, MacKenzie wanted her pole exercise studio there.

“Main Street is growing so much, there are so many different restaurants, a consignment store and other things to do,” MacKenzie enthuses, saying she makes enough money from her classes, which include pole exercise, burlesque, CIZE (a hip hop dance workout) and some exotic dancing.

She adds, “I'm involved with the Chamber so I know the business owners. I like to shop local.”

Waterville has another advantage for businesses in that has a Foreign Trade Zone, which means companies meeting certain criteria get tax and tariff breaks on imports and exports, Lindlof says.

Olsen of Waterville Main Street says it's important to be patient in turning around communities to make lasting changes.

“There are formal and informal spheres of influence, and you have to understand them,” she says.

Read more

Italian market to open in former downtown Waterville food co-op space

Comments