Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

A home of her own: More women of all income levels are buying homes in Maine and nationwide

Photo / Tim Greenway

Sarah Henderson, a single mother of four, is helping build a home for herself and her kids through Habitat for Humanity.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Sarah Henderson, a single mother of four, is helping build a home for herself and her kids through Habitat for Humanity.

More Information

Sarah Henderson still can’t believe she’ll soon own her own home, even though she’s lending a hand to the Habitat for Humanity of Greater Portland building crew by assembling window frames and hammering nails onto the roof.

“It still feels unreal,” the 31-year-old single mother of four says of her future home in South Portland. It’s an easier commute to and from the McDonald’s restaurant she manages than her current rental apartment in York County.

“I make Big Macs for a living. I don’t build floors and walls — but I do now,” she says. “How crazy is that?” Keen to be on the building site full-time, she says, “If I could stop working right now and work on my house every single day, I would.”

In Maine and nationwide, the number of single women buying homes is rising at a fast clip, outpacing their oft better-paid male peers to become financially and residentially independent. Women weren’t even allowed to hold property in their own names in all states until 1900, and it wasn’t until the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 that women were allowed to apply for and obtain a mortgage in their own name, without a male co-signer.

Today, women of all ages and income levels are embracing homeownership, keeping brokers like Dava Davin busy. She’s the founder and CEO of Portside Real Estate Group, a Falmouth-based agency with a focus on southern Maine and southeastern New Hampshire, and says she’s getting more queries from first-time female homebuyers.

“Women homeowners demonstrate a strong work ethic and disciplined savings habits, which can help them successfully navigate the process of applying for a mortgage and saving for a down payment,” she says. “Additionally, women are more likely to embrace the commitment it takes to own a home and the challenges that arise with home repairs and maintenance.”

Her outlook: “As more women than men are currently enrolled in college in the U.S., we may continue to see more women owning homes than men in the future. It is my hope that, as this trend persists, we will also see progress in closing the gender pay gap.”

All the single ladies

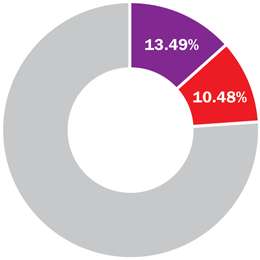

Nationwide, single women own 10.8 million owner-occupied homes or close to 13% of the total, while single men own about 8 million or around 10%, according to a study of U.S. Census data by online marketplace Lending Tree released in January.

In Maine, where the median home price was $329,250, in February single women own and occupy close to 60,000 homes, or 13.5% of the total, while single men own and occupy 46,555 homes or 10.5%, Lending Tree found. The difference is close to the national average.

Another report, published in 2021 by the National Association of Realtors, shows that while the proportion of married buyers in the U.S. has decreased since the group began collecting data in 1981, the proportion of single female buyers has gone up—owing in part to lower marriage rates. The research also shows that single women are twice as likely to buy a home to be near friends and family, which also holds true for divorced or widowed women.

For all singles, the desire to own a home of their own is the top reason to buy, a finding validated by Bella DePaulo, an academic affiliate in the department of psychological and brain sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of the upcoming book “Single at Heart.”

“One of the stereotypes about single people is that they are not very attached to the places where they live. They will just up and move at a moment’s notice,” she says. “Some single people do like to do that, but others care very much about where they live. They make friends, get involved in the community, and put down roots. Owning a home is one way of investing in your single life and in the place where you live.” On single women specifically, she notes that they often know what they want in a home, “and they make the fewest compromises on things like the condition of the home and its distance from friends or family or their job.”

Her advice to first-time buyers nervous about taking the plunge: “Think about the joy of having a place that is all yours, that you can furnish and decorate and use exactly as you please. Let those feelings of joy win out over any anxieties about the whole process of buying a home.”

That’s easier said than done in Maine, particularly the two southernmost counties where median prices are the highest and inventory remains tight.

Money matters

Lending Tree researchers offer a few explanations for how women translate fewer dollars earned into more homes, including evidence suggesting that single women prioritize home ownership more than their male counterparts. They also note that the gender wage gap is less pronounced for younger generations, citing Pew Research Center data showing that women under 30 earn at least as much as their male peers in 22 U.S. metropolitan areas.

Another report, based on a Bank of America survey of 2,000 adults in 2021, found that while two out of three single women said they’d rather not wait until marriage to buy a home and feel emotionally ready to dive into homeownership, cash on hand remains the biggest hurdle. Single women also want to save more for a down payment, improve their credit score and figure out their long-term plans before buying a house. With that goal in mind, 70% of single women surveyed said that they are saving money first, then spending what’s left after covering the basics, compared to 63% of single men going that route.

Saving was a priority for Emma Rose, 35, a freelance marketing content and curriculum writer for higher education, before buying her first home in Hampden. That was in 2018, when interest rates were much lower than they are today and the housing market was “pretty OK,” she says.

Living with her parents at the time after returning to Maine from Norfolk, Va. after a divorce, she says, “My parents were great to let me stay with them, but it’s also a little bit demoralizing to be living in your parents’ house in your 20s. There’s not a lot of privacy.” Being forced take phone calls in her car prompted Rose to make a change and set herself up financially to buy a 740-square-foot dwelling in Hampden for $104,000 in March 2018.

“In some ways, I was just very lucky,” she says. “I’d managed to pay of off student loans and had a small chunk of money squirreled away that allowed me to cover the expenses associated with the loan. I’m also a big believer in savings and living below your means, so I was able to show the lender that I had a good financial cushion.” She also added to her freelance income with a part-time job she was able to quit within a few months of buying the house.

The day that her banker slid her new house keys across the table, she called her best friend from her new place on FaceTime to show her the place and then “took the longest shower of my life.”

In 2021 to take advantage of low interest rates, Rose refinanced her home that she says saved her around $40,000. She also secured a home equity line of credit for home improvement projects.

Now living about 25 minutes from her parents, she says, “Now I have my own space and our relationship is much better.”

Self-educated buyer

Much newer to homeownership, 58-year-old Denise Williams bought her first abode last year in Windham 11 years after getting divorced. Williams, an associate relations manager at Hannaford in Yarmouth, did so in May 2022 via a federal loan program for low-income applicants seeking housing in rural areas she heard about from Chelsey Torrey, a mortgage loan officer with Town & Country Federal Credit Union and former loan technician with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development.

Williams paid $370,000 for her home with a 3% interest rate through a USDA Rural Development Direct Loan that Torrey helped her process.

“At the time interest rates were between 6% and 7%, and without the loan. I would have had to make a significant down payment, which I didn’t have,” Williams says. With the loan, “I only had to put closing costs down.” Out of 14 such loans Torrey processed in 2022, seven were for single women and two were for women who were their household’s primary income earners.

“It’s a real labor of love, but reaching the closing table with those who may have never thought owning a home would be possible for them is everything to me,” Torrey says.

Well before embarking on her search, Williams got up to speed on what she needed to know by listening to the podcast “How to Buy a Home with David Sidoni,” and encourages all women to be informed buyers of everything from cars to houses, saying, “If you’re educated, nobody’s going to take advantage of you.”

She also hopes her home-buying experience inspires her daughter and son, both in their early 30s, to go the same route.

.“I told them, ‘If I can do this, you guys can do it, too, and I’ll show you how,’” she says. “My son is moving in next month for the summer to save some money so he can do the same.”

Habitat’s ‘sweat equity’

Back in South Portland, while the price of Henderson’s home-to-be won’t be known until closing, new homes generally cost around $320,000 to build, according to Kate Weidner, development director of Habitat for Humanity of Greater Portland.

She notes that the average mortgage is $120,000 and is based on a monthly payment that doesn’t exceed 30% of a buyer’s income, including taxes and insurance. The home value’s remaining balance is held by Habitat and is not payable unless the home is sold.

So far, the nonprofit has built 93 homes for first-time homeowners, with plans to add eight in South Portland (including Henderson’s) and 12 in Standish set to break ground this summer.

“Thanks to funding we received from Cumberland County’s pot of [the] American Rescue Plan Act, we will have built all 20 of those homes by the end of 2026,” Weidner says.

As part of her arrangement with Habitat, Henderson has to complete 275 hours of “sweat equity, which includes financial education classes, volunteering at the construction site and at the organization’s ReStore and community service in the city she’s moving to (which also happens to be where she grew up).

“We find that when homeowners immerse themselves in the community through their service hours and building their home and their future neighbor’s home, it gives them a sense of connection that simply purchasing a home doesn’t provide,” Weidner says. “It gives them a chance to get to know their neighbors and existing community services while giving them an immediate ownership in that community.”

Henderson’s house is slated to be finished this summer, and she’s committed to living up to her part of the contract with Habitat by maintaining her credit rating and putting in her hours.

“It’s an amazing deal,” she says, “but it’s not free.” Resolved not to buy another car until after the house is hers, she often drives by the building site at night just to make sure her dream is real.

0 Comments