A local lawyer launches a crusade to revive the town with 14,000 feet of steel cable

For more than a century, Rumford's downtown has been bookended by two powerful residents: the paper mill to the east and Pennacook Falls to the west. The mill here has long been the center of the town's economy. But as it continues its decades-long decline, one local lawyer has become obsessed with finding the town's salvation in the falls.

The largest waterfall east of Niagara, Pennacook Falls, also known as Rumford Falls, is a constant and mercurial presence. This stretch of the Androscoggin River has been known to rise as much as 20 feet during heavy rain, making the normally tame waters roar over the rocks and mist spit high into the air. Every day, the river slips, swirls and churns past the Rumford Falls Hydro dam on the Androscoggin River, down the falls and under the lime green beams of Memorial Bridge, and along the western edge of Rumford Island, the tiny downtown where empty sidewalks meet the stately brick-and-granite buildings that recall this paper town's long-lost Gilded Age.

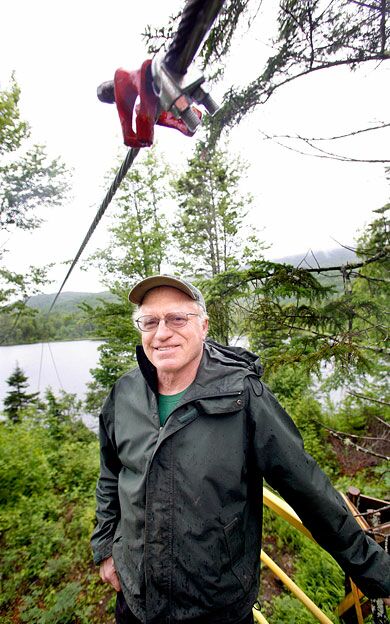

It's this historic pocket, with its handful of shops and restaurants stubbornly thriving among empty storefronts, that lifelong resident Tom Carey believes the falls can rescue. His plan is to turn Rumford Falls into a world-class destination for zip lining, a popular adrenaline ride in which a person is strapped into a harness, attached to a roller on a steel cable, and sent sliding from one platform to another at speeds up to 60 miles per hour. Carey and his engineer, Newry's Jim Sysko, believe criss-crossing six zip lines totaling more than 14,000 feet over the falls and the downtown will attract visitors who otherwise would pass right by town. The plan is to entice out-of-towners onto the line, shoot them over the falls a few times, and encourage them to calm their nerves afterward with dinner, a show, a T-shirt with a catchy slogan commemorating the ride.

“You take a walk down Congress Street and you talk to people before this project came along and things weren't getting better,” Carey says one recent afternoon, as he and Sysko point out the proposed zip line routes, which include a cable down the middle of Congress Street, the downtown's central throughway. If all goes according to plan, the quiet here might soon be punctuated by the screams of harnessed tourists whooshing by overhead. “It wasn't going to be a business that just drops in on us,” Carey says of the town's economic knight-in-shining-armor. “You have to take what's here and maximize it.”

A lanky trial attorney with a mop of grey curls, Carey had competed days before with his adult son in a Colorado Tough Mudder, an extreme race during which he had been driven face-first into mud after being electrocuted by a live wire in the back of the head. Carey describes the Mudder as one of the most difficult and painful things he's ever done. He says he had a blast. The two extremes seem to pair just fine in his mind.

Getting shocked en route to the finish line might be apt preparation for the zip line challenge. Since Carey latched onto the idea this winter — after someone, he doesn't remember who, blurted it out during a how-do-we-revive-Rumford meeting of the volunteer business coalition Envision Rumford! — he's made it his mission to bring zip lines to town despite daunting resistance from state and federal agencies, the fact that no one has offered to build or operate the zip lines, and the persistent opinion among some folks around here that the whole thing is crazy.

“Some people laugh at the idea and some people are all for it,” says Lisa Cormier, owner of Lisa's Barber Shop on Congress Street. “People are definitely talking about it.”

Cormier has lived in town her whole life. When asked how Rumford has changed, she relates the same story of decline that many here tell. Looking down the empty main street one recent afternoon, she says the downtown is worlds away from what she knew as a child, when her mother could do all of her Christmas shopping here at department stores like J.C. Penney. Cormier is a youthful blonde with trendy wide-framed plastic glasses. As she reminisces, the only other person on the block, a sunburned, middle-aged man in jeans and a T-shirt, lingers in front of the post office, squinting curiously. Cormier had heard that Carey intends to string zip lines along a half-mile stretch of the falls, which sounds good to her, but she's not sure about people flying down Congress Street over traffic.

“Oh, I don't know,” she says, looking up and frowning. “I don't know if I'd like it coming down the street.”

Finding a solution

Carey is pursuing zip lines as a member of Envision Rumford!, a new group of about a dozen business owners focusing on improving commerce on Rumford Island, a finger of land bordered by the Androscoggin River and a canal with a business district about two blocks wide. The island contains the town's main artery, the four-block-long Congress Street, its post office, town hall and many of its locally owned shops, restaurants and bars. Through the boom years of the 1960s and '70s, this downtown was the place to be. There was music and dancing at the local Mechanics Hall, packs of teenagers lounged around on the sidewalk, and popular department stores attracted shoppers from around the region.

Today, Rumford's downtown is as empty as a movie set waiting for the cast to show up. On a recent evening, a handful of residents made their separate ways around Congress Street, past shops with flapping “Open” flags and “Thumbs Up for Zip Lines!” stickers in the windows.

“I don't know what it would take to turn Rumford around,” says 58-year-old Greg Adley, a paper winder and brother of a town selectman, who was heading into Chisholm's bar to celebrate the end of a multi-day shift at NewPage. Adley thinks the zip line is a “cool idea” that he wants to try with his daughter, but he wonders what tourists will do even if they come to town, since many of the storefronts are empty. “It's a challenge,” he says. “If the storefronts were all filled, things would be different.”

Whatever their opinion on zip lines, it seems most in town agree that something has to be done, and fast, to fill the growing void left by the struggling paper mill. NewPage's Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing in September is just the latest in its steady decline as a central employer here since the 1960s, when it employed more than 3,000 of the town's 10,000 residents. Though it remains North America's largest maker of coated paper and a major taxpayer in town (46% of Rumford's taxes come from NewPage), after years of mechanization and cutbacks, NewPage now employs only 750 people, according to the Sun Journal.

As the jobs left town, so did the people — Rumford's population has dwindled to just over 6,000, with a median income ($28,000 in 2009, the most recent data available) at slightly more than half that of the state's. As one resident put it, “When the mill went down, the town went down, too.”

But there have been successes this year — an Amato's sandwich shop recently moved into one of Rumford's three new TIF districts, and there are plans to create an inter-town network of mountain bike trails that, with the zip lines, could help the town transition to a recreation economy. Envision Rumford! along with area businesses created a map for tourists and is pushing for clearer signs to help strangers navigate the downtown. People seem eager for solutions: All of the residents who initially said they don't like the zip line idea — because they worry that it would be dangerous, or because they incorrectly assume the town would build and operate it, or, as one woman said, because people on the Congress Street run might throw things at pedestrians — later said they are open to it as long as it attracts tourists with money.

“If it brings more revenue to Rumford, more power to them,” says 49-year-old Barry McIntyre, a custodian at the Sunday River ski resort who has always lived in Rumford. “We need something.”

Curious residents won't have to wait long to try zip lining. To encourage public buy-in, Carey and Sysko hope to offer rides on the Fourth of July on two 500-foot zip lines strung between a pair of dump trucks in Rumford's Hosmer Field.

Maneuvering the regulatory route

Neither the town nor the zip line supporters know exactly how much the project might benefit the local economy, nor have they solicited a builder or operator for the lines. Bradd Morse, owner of the zip line construction company Canopy Tours Inc., spoke about average costs during an April public meeting on the project, though he stressed that his advice was informal as he is not familiar with Rumford's plans. Carey hopes that the town will eventually put out a request for proposals to companies like Morse's to build and operate the zip lines. Morse says zip lines typically cost from $500,000 to $2 million to build, depending on the type of platforms, and construction takes six months to one year. The network of zip lines would likely employ 35-40 people during the peak season.

While Morse says zip lines sell tickets based on the perception of danger, he claims they are in fact very safe, and permitting is often relatively simple once that misconception is resolved. He says, however, that some projects are abandoned because permitting drags on for too long, especially projects, like Rumford's, that cross public lands. “The process gets so bogged down that people just bail on it,” he says.

Rumford's zip lines currently have the support of the town, the Western Maine Economic Development Council, and many island businesses. But Massachusetts-based Brookfield Renewable Power, which owns the land on which one of the key launches would be built, has expressed concerns about zip-line safety and has warned Carey that the permitting process with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission will take at least a year, with no guarantee of success.

The Maine Department of Transportation had also put up a roadblock, saying no to the project because zip liners could distract drivers. But in late June, after Carey leveraged the support of state legislators, the county commissioners, and Western Maine Economic Development Council Executive Director Glen Holmes, the MDOT consented to a tour of the proposed site and has reopened dialogue on the plan.

Carey is optimistic that with his clear and consistent effort, tourists will one day careen over Rumford at speeds topping 30 miles per hour. “If there's any wiggle room at all,” he says, “we're going to explore it.”

Comments