A West Newfield startup attempts to erase mobile communication barriers

The next wave in mobile communications might come from a basement in West Newfield.

Investors, including the state of Maine, certainly hope so. They're putting nearly $1 million into Newfield Design Inc., the brainchild of inventor Robert Stone.

Backers believe Stone's creation — the Expandable Radio Control System — is a unique, flexible, valuable product in the world of land mobile radio. LMR refers to any multimodal communications system used by companies, governments or other organizations to direct the movement of people and materials, address safety and security, and provide agile response.

Users include public safety agencies, utilities, railroads, the military, manufacturers and a wide variety of small businesses — from delivery companies to landscapers to utilities, or anyone for whom instant, error-free communications is mission-critical.

"Having a communications network that talks to each other effectively is something that's been elusive in this country," Newfield Design CEO James Colony says. "There's different languages, different devices. People died on 9/11 because of it. We talk about the public safety markets because that's what resonates with people."

Another solid push for LMR comes from government. The Federal Communications Commission's "narrowbanding" mandate requires radio users of all kinds to use less of the spectrum by Jan. 1, 2013.

With industrial need for quick, error-free communication and the government's need to narrow the spectrum, next-era LMR systems currently generate more than $8 billion in annual sales, according to a Newfield Design memo to investors. Industry reports see that figure doubling, to $16.3 billion, by 2017.

Newfield could see a piece of that, if it isn't taken out first.

Company officials and investors have noted the North American market for land mobile radio is dominated by Motorola and Harris Corp., "both of which are excellent candidates as potential exit providers," the company said in its prospectus.

Colony notes Harris recently spent $675 million to buy Tyco's radio communications business. "This stuff happens all the time," he says. "If you don't want to do R&D, you can buy R&D."

"The most logical [exit] is one of the big players will want to buy us because it's a technological edge," Colony says, "and it would let them sell more handsets, which is what they want to do.

"The technology is unique in the industry," Colony says. "Just within the LMR industry, it will have significant value. But we don't limit the avenues as an exit strategy just to the major players in LMR. There are other players who would benefit."

That the next generation in mobile communications might come from a startup off a dirt road in southern Maine surprises some, but not Newfield's principals or investors.

"They're going to be producing some good tech jobs in Maine," says Jayme Okma Lee, an associate at Brunswick-based Small Enterprise Growth Fund, the state-run investment fund that was one of 15 entities to invest a total of $660,000 in Newfield Design in an equity offering last month.

"It's a great positive for the state," Okma Lee says. "An even bigger positive is this idea of growing a network of high-growth entrepreneurs in Maine."

The company expects it will be cash-flow positive in its first year. By the third year, it says it will have a $3.1 million payroll, ship 14,500 units, have operating income beyond $22 million and employ dozens at two Maine-owned contract manufacturers.

The company has filed one provisional patent application. It's using its startup cash to hire programmers and system engineers. Developers are finalizing software code for nine different products and testing them with digital signal processors that do 80 million calculations a second.

Newfield also has its first ERCS customer: the public school system in Loudoun County, Va., which employs a system called SmartLink that Stone designed on his own in the late 1980s and then sold to a company called CalAmp. It's a provisional deal that could be worth $185,000 to Newfield and provide the company a roadmap for forward sales.

Better connections

The Expandable Radio Control System is a box the size of a paperback novel. Inside are two circuit boards with chips programmed to translate 47 communication protocols, letting a variety of handset users talk to each other without having to buy an entirely new system.

The concept of interoperability is a big deal to public safety officials.

Stone said 33 years as a volunteer firefighter helped him gain appreciation of the "extreme value of emergency communications."

"The older analog radios that fire, EMS and most of the police are using in Maine are 1970-level technology," Stone says. "They transmit no ID, have no serial numbers, nor can they be killed" in case of an open mic or a jamming incident. These features of the older analog radios can render an entire system inoperable.

Newfield's ERCS can connect separate radio systems. "Two police departments in towns adjacent to each other can each have their own independent radio system. When they plug our boxes in, they can then talk to the other police department just like they were on the same radio frequency," using their original equipment, says Stone.

It's done by equipping a repeater site with an ERCS controller, plugging that into a wide-area network or, if necessary, the Internet, then sending code to the ERCS to unlock whatever level of operating software the client has purchased.

"If you had 10 portables and two repeaters, you're looking at a cost to the town of probably in the area of $35,000 [to replace the system with a similar one]," Stone says. "You can put our product on for about $10,000 ... you're going to get a lot of neat features and you're also going to narrowband your system."

Colony says public safety, like fire, police and ambulance is "only one-third of our market. The other two-thirds are much more lucrative, with a much shorter sales cycle. But it's not as compelling a story."

The "other two-thirds" of the ERCS market is in the commercial and industrial sectors: logging and trucking operations, oil refineries, taxi services and others currently relying on piecemeal communication systems.

Sales will be through established radio equipment dealers. Given all the disparate devices and repeaters in a system, Colony says some clients will need $100,000 or more in Newfield products to cover all the repeaters in their network.

"That's key to sales," Colony says. "You can use your existing communications footprint. You don't have to reinvent the wheel."

Potential for jobs

Inside the ERCS box is one standard controller circuit board, plus one of nine different circuit boards the company says will adapt to every possible system architecture in existence — and many in the future no one's developed yet, says Colony — using digital signal processors, programmable gate arrays and proprietary firmware hard-written into the device.

Designing a system that can work with all older handsets and talk to different computer languages over distances is a task Colony says is not "just [about] people talking to people, it's also machines talking to machines."

"Have you ever read 'Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy'? We make the babel fish of radio," he says, referring to a fictitious animal in Douglas Adams' books that performs instant translations of certain galactic languages, of which there are millions. "It doesn't have to talk to all the languages in the universe, it has to talk to these forty-seven."

ERCS is in testing, including environmental trials in high- and low-temperature settings and circuitry tests Colony describes as military-grade, to ensure the system is — in LMR parlance — "always on."

Newfield signed two Maine manufacturers — Saunders Electronics in South Portland and Enercon Technologies in Gray — to produce the boxes.

"There's no reason to go to China to stuff boards," Colony said. "A lot of that [manufacturing] is actually coming back. It's not labor intensive. It's know-how intensive.

"Creating jobs in Maine is something Bob Stone talks about," Colony says. "You don't have to worry about the quality. They know exactly what they're doing."

Stone, 69, says "there's a fabulous manufacturing capability in this state" and bristles when asked about the litany of complaints about Maine's business environment, or finding skilled workers. "That ability is here," he says.

He notes that West Newfield — population 1,328 in 2000 — was once the largest town in York County, with five-story factories making mechanical parts for horse-drawn carriages. "This was a very industrious area that actually required skilled labor capable of assembling what they were building," he says.

"We need to create jobs in this state that are more high tech, but suited for anyone," Stone says. "Most people, if they have any basic mechanical dexterity, can learn to assemble products. So then we could provide jobs for everybody."

In addition to in-state manufacturing, Newfield has graduate computer science students from the University of Southern Maine writing code for the ERCS system.

When Stone — who founded Newfield Design in 2008 — crows about doing business in Maine, it's not only because the state is his largest investor.

"There is a tremendous amount of advantage to being in Maine," he says. "It's a place where you can work and live with some sanity compared to living in the other states. It's close enough to the other states where there is a lot of high-tech business. You can easily bring that high-tech business back to Maine and do it here."

Industry leader

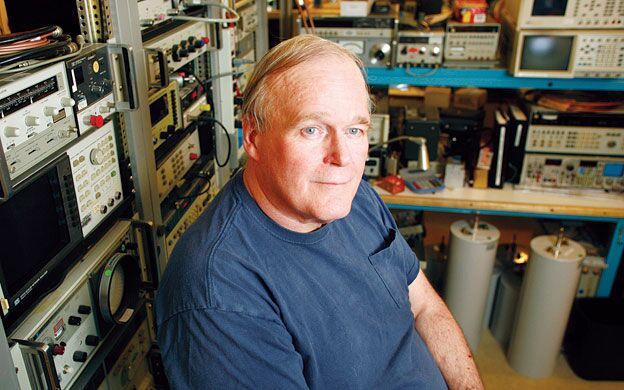

Many of the 10 employees the company hopes to hire by the end of June work out of a lab in the basement of Stone's West Newfield home that must have resembled David Packard's garage in the days before Hewlett-Packard. It's a big room chock full of imposing radio and technology equipment of various vintage and repair.

When discussing the company's technology, talk invariably revolves around Stone, a friendly guy who speaks non-technical English, collects rare show cats and runs the business with family members whenever possible.

Okma Lee, of the lead investor Small Enterprise Growth Fund, says Stone "is well regarded in the industry as being a very smart guy, someone who knows the industry… The technology was at a point where he needed to raise capital in order to bring this to reality."

Stone started his work in communications electronics at the age of 10, when he worked as a "summertime assistant" to his father, a development engineer for the Department of Defense. He studied at the University of Hartford and calls himself a "course sampler" in school. But he employed his skill tenaciously, becoming the youngest person ever to pass the 1st Class Commercial FCC licensing exam.

"Since then," he says with modest disappointment, "I've been eclipsed."

In high school, he worked for Timex Corp. building artillery fuses in its weapons division and helped design telephone switches for Norelco and Dictagraph in the early part of the telephone age.

He came to Maine to help deal with his aging parents' estate, which included a summer camp in Sanford. He ended up staying and bought a house in Newfield in 1976.

Of his colleague, Colony says, "He has a unique skill set that can't be replicated."

Money to grow

The Small Enterprise Growth Fund — which currently has a $13 million portfolio, funded with state and federal sources — chipped in $275,000 as what Okma Lee called a "first investment" in Newfield Design, giving it the lead stake among a group of 15 investors that includes private venture firms Boston Harbor Angels and Maine Angels.

"We look to invest in Maine companies that have a potential for high growth and public benefit," says Okma Lee. The Small Enterprise Growth Fund tends to "stay very involved with our portfolio companies," occupying a seat on the board and requiring monthly CEO and financial reports, she says.

"Part of it is building examples out there," she says. "There are CEOs and those who have the experience of turning an idea into a multimillion-dollar business. The more people in Maine who can do that and have done that, the more viable that becomes for other people."

Okma Lee says she can invest up to $500,000 in any one company. "We may invest more in Newfield," she adds.

Newfield Design landed another public investment with a Maine Technology Institute development loan of $495,751 in April. The company already had made a splash in the Maine venture community by winning the grand prize — $100,000 in convertible debt — in last year's Juice 3.0 Pitch Contest.

Joe Migliaccio, manager of MTI's business innovation program, says the state's investment seeks to encourage high-growth companies to succeed and stay here. "Entrepreneurs and companies, small incubated ones, tend to be sticky, tend to stick around where they grew up," he says.

As for the employees at Newfield Design, there's little doubt about the future.

"No one has invented what Bob Stone has invented," Colony says. "It's simply not available. He has created new art."

Editor's note: This story has been corrected from its original version.

Comments