Back on the clock: Why some Mainers are choosing to ‘unretire’ and keep working well into their 80s

Photo / fred field

Retired veterinarian Mark Beever, 66, fixes timepieces out of his Cornish garage business, the Hickory Dickory Doc Clock Shop.

Photo / fred field

Retired veterinarian Mark Beever, 66, fixes timepieces out of his Cornish garage business, the Hickory Dickory Doc Clock Shop.

The animal doctor became a clock doctor. Retired veterinarian Mark Beever fixes timepieces for a living from a home-garage workshop in Cornish called the Hickory Dickory Doc Clock Shop.

“I sort of feel like I’m still able to do surgery,” he says, “only not on living critters.”

The 66-year-old, who gave up his vet practice in late 2019, is among a growing number of retirees choosing to return to the workforce in what is increasingly known as “unretiring.” Motivations vary from financial needs to staying active and intellectually stimulated.

In Beever’s case, it’s all of the above, turning a lifelong love of clocks he inherited from his mother and grandfather into an encore career. Based on a dead-end rural road, Beever takes repairs by appointment only, working up to eight hours a day to keep up with demand.

Though he misses interacting with his former patients and their human families, Beever likes setting his own hours as a self-employed entrepreneur and the earning power that brings.

“I’m looking on it as a second career, and it’s definitely helping with some household expenses,” he says.

Whether working alone like Beever or as members of a team, retirees across Maine — the oldest state in the nation, with a median age of 44.8 — are finding encore careers. That includes people taking the leap into new professions, as statewide unemployment remains well below 4% and many industries struggle with staffing.

Back-to-work momentum

Although the Maine Department of Labor does not track retirees who have gone back to work, U.S. data compiled for Mainebiz by Nick Bunker of the Indeed Hiring Lab show the national percentage has hovered around 3% over the past five years and was at 2.7% in November 2023.

The back-to-work momentum follows a surge in retirements at the start of the pandemic, including those who retired the Great Resignation.

While there were 2.4 million more retirements than expected in 2020, by 2022 around 1.5 million of those individuals had reentered the workforce, according to a September 2023 T. Rowe Price report citing data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

“The pandemic may have created an unusually large wave of retirees leaving and returning to the workforce, but the trend of working in retirement is going strong,” the report notes.

Out of more than 4,000 retirees surveyed, 20% were working full- or part-time while 7% were looking for employment.

The study found that there are a lot of benefits and motivations for why retirees chose to work part or full-time. While women and singles cite income as their main motivation, for their male peers the main focus was on social connections.

Bye-bye, mai tais

Why is unretirement catching on as a concept and lifestyle?

Barbara Babkirk, a Portland-based career counselor and transition coach to professionals typically aged 50 and older, points to three main drivers: Purpose, social connection and structure.

So does Jill Hibyan, a Portland-based private client advisor with F.L.Putnam who says she knows a few folks who have “retired” three times.

“Working in retirement can be very rewarding,” she says. “It’s a way to stay social, connected and physically active. Working in retirement can provide meaning and purpose, and it can help you remain intellectually stimulated.”

As far as financial planning, she likes to remind people that monthly income can come from many sources, from Social Security benefits to rental income and, in some cases, a part-time or less-stressful full-time job.

Another manifestation of the work-as-long-as-you-want-to mindset: “There’s a whole wave of people right now who don’t like the word ‘retirement,’ which conjures up images of sitting on the beach in Florida and drinking mai tais,” says Polly Chandler, a California-based transition coach with Third Half Advisors. “For a lot of people, that’s not what they want to do — they could live another 30 years. That’s a lot of mai tais.”

For Bobbi Ackerman, a retired teacher in Brooksville, that energy comes from her horses and goats, who are an important part of the literacy tutoring she offers to youngsters ages 5 to 16. Along with reading and writing, lessons include haltering, leading, brushing and learning parts of the animal in what is known as equine-assisted learning.

Ackerman charges $50 an hour but offers free lessons to those who can’t afford to pay, and says she loves what she does.

“I just can’t imagine not being with kids and horses and goats,” she says. “I feel like I am still just getting into my stride.”

For others, particularly in the armed forces, “retiring” can mean leaving the military for civilian life well before retirement age. Take Michael Murnane, a 51-year-old Navy veteran now leading operations at Aero Heating & Ventilation Inc., a Westbrook-based fabricator and installer of sheet metal ductwork owned by its 65 employees.

While he came into the job without any experience in that sector, Murnane draws on the leadership skills he honed in Afghanistan and other deployments as he adjusts to an environment without uniforms and reminds himself to steer clear of military jargon and acronyms.

“Here it’s so much more rewarding than had I had stayed in my comfort zone.”

From publishing to hospitality

Like many of his peers, 71-year-old Don Golini has also chosen to work in a new industry while “Enjoying Act Two,” as he declares in his LinkedIn profile.

His first act consisted of 40 years in educational publishing. After switching gears to hospitality and moving to Maine during the pandemic, he landed a part-time front-desk job in April 2021 with the Nonantum Resort in Kennebunkport.

“I was never a person who could just not work, and wanted to find something fairly simple where I could just show up, do something three or four days a week, go home and that would be the end of it,” he says.

Beyond his reception-desk duties, he oversees the resort’s student employment programs, including a 10-week summer internship program reinstituted in 2022 and, as of 2023, opened to applications from all majors.

“This way we were able to attract a broader range of students who might not have considered a career in hospitality,” says Golini.

Besides manning the front desk three days a week during the season, Golini can put in as many additional hours as he needs for his other responsibities — leaving plenty of time for leisure activities and volunteering.

Grateful to have a pension, Social Security and a 401(k) to supplement his part-time earnings, Golini says he feels fortunate to be working not because he has to, but because he wants to.

To peers thinking of the next career move, he says: “It’s always good to have a plan, but you need to be open to possibilities as well.”

Meet the Makers

For some people, taking time off after closing the books on a career is just the reboot they need to figure out their next chapter. That was the case for Andrea Cianchette Maker, who stepped down as the head of Pierce Atwood’s government practice relations group in May 2021.

“The intention at the time was to enter what’s called liminal time,” or an in-between period, the 67-year-old says. “I shed some things I was doing, I took care of my family and myself, and declined opportunities to get involved in different activities because nothing rally sang to me.”

She also read “The Second Mountain,” a book by David Brooks that touches on how retirees move from a professional career into a passion. Somewhat unexpectedly, Maker says she found her passion in leading FocusMaine, a private sector-led initiative to create Maine jobs in agriculture, aquaculture and biopharmaceuticals she co-founded in 2014 with Michael Dubyak.

As president of FocusMaine since November 2023, Maker leads a staff of five without any regrets about leaving the legal profession.

“When I retired, I was very careful to say I was retiring from my law practice,” she says. “The career I had was always around strengthening Maine’s economy and creating jobs for Maine people, but I don’t miss the challenge of juggling a dozen clients,” she says. At FocusMaine, “I am very motivated to dedicate myself to one initiative that will create a lasting impact on the quality of life for Maine families.”

Along similar lines, her husband, Scott Maker, has carved out a new career for himself after retiring from Unum in 2020. Nine months after leaving his job as deputy general counsel at the disability insurer and group benefits provider, he teamed up with a fellow former lawyer to start WoodworthMaker, a mediation and arbitration business with a nationwide clientele.

Reflecting on the post-retirement pivots he and his wife both made, the 66-year-old says. “We both failed at traditional retirement but succeeded in the new version of retirement.”

‘88 is the new 50’

It’s not just people in their 60s who are reinventing themselves professionally.

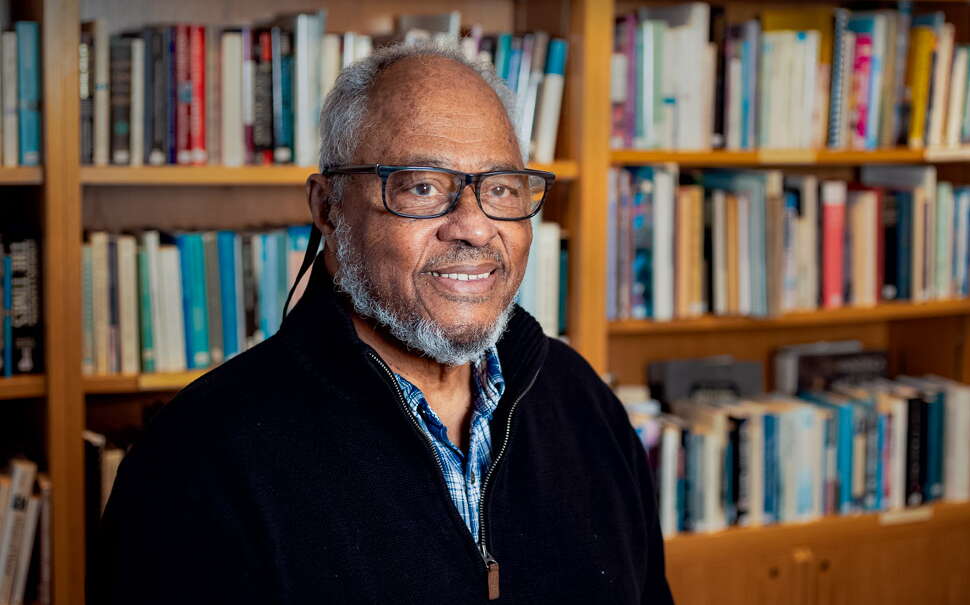

So is Bob Greene, a retired journalist who spent 36 years at the Associated Press covering stories from the funeral of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and floods on the Mississippi River to professional tennis around the world.

In retirement, he’s devoted a lot of free time to studying history and genealogy, sparked by his research into his own family’s roots in Maine which he traces back to 1750 in Cumberland.

He also has a paying job, as a part-time Social Security disability hearing officer about 10 to 12 hours a week. He started there in 2001 after moving back to Portland, from New York City.

For the past several years, the Minot resident has also been teaching at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at the University of Southern Maine, whose classes are for people 50 years and older.

“I like the fact that I am able to enlighten people about our past,” says Greene, who will be teaching a course this winter on Zoom on the Black history of Maine. He’s taught the class before, always in person, and plans to update the curriculum with some of his research findings, including little-known facts about slaves in Maine.

While Osher Lifelong Learning Institute teachers are not paid, many like Greene relish the opportunity to share their knowledge and insights with students who are there because they want to learn.

“For many OLLI instructors, teaching is a chance to dream your dreams — to share the passions of a lifetime or to build on new ideas and interests,” says Donna Anderson, the institute’s director.

Greene’s weekly course is offered this January and February, the month he turns 88. Noting that “88 is the new 50,” Greene hopes to keep his part-time Social Security job as long as he can.

“I’ll work until they tell me not to or that I can’t,” he says.

Meanwhile in rural Cornish, Mark Beever hopes to keep fixing clocks as long as time permits.

“I don’t have a particular timetable on when to stop this,” Beever says, “but it’s definitely keeping me busy and I really enjoy what I’m doing.” At this stage in his life, busy is exactly what he wants.

0 Comments