Country lawyer: Rural practices have rewards, but many areas of Maine need attorneys

Photo / Fred Field

Ben Everett, right, and his mentor, Adam Swanson, say Maine Law’s Rural Law Fellowship Program is a good start for attracting rural attorneys. Everett now works for Swanson’s Presque Isle firm, Swanson Law.

Photo / Fred Field

Ben Everett, right, and his mentor, Adam Swanson, say Maine Law’s Rural Law Fellowship Program is a good start for attracting rural attorneys. Everett now works for Swanson’s Presque Isle firm, Swanson Law.

As a newly minted lawyer who grew up in Aroostook County, Ben Everett’s greatest dream was to return home to pursue his practice.

A Maine Law ’21 graduate, his dream got a boost when he signed up for the Portland school’s Rural Law Fellowship Program, which pairs students with rural lawyers who serve as mentors.

“For me that was a no-brainer,” says Everett. “I said, ‘I know exactly what I want to do when I graduate from law school.’”

Originally from Fort Fairfield, Everett was a non-traditional student who did a stint in the military, then worked in Presque Isle as paramedic for a decade.

Intrigued by the law, he enrolled at Maine Law and signed up for the fellowship program, serving two summers under the mentorship of Adam Swanson, who owns Swanson Law in Presque Isle.

Upon graduation in May, Everett was hired by Swanson as an associate attorney. The program was mutually beneficial.

“When he was participating in the fellowship, I set up a desk for him in my office. If a call came in, provided the caller consented, Ben would listen along and could ask me questions afterward,” says Swanson. “He reviewed and memo’d files, and assisted in the drafting of pleadings. He’d also go to court with me.”

Swanson offered Everett a position before he even graduated.

“All we had to do was give him office space and he was ready to roll,” says Swanson.

A crisis

“Ready to roll” just about sums up a rural Maine attorney’s practice. Rural lawyers typically have more generalized practices than those at large urban law firms. New attorneys can jump into the workings of the legal system more quickly.

“I have friends in larger firms who might not step into a courtroom for the first five years of their practice,” says Everett. “But I know I’m going to participate in jury trial selection to do trials, which is a phenomenal opportunity for a young professional.”

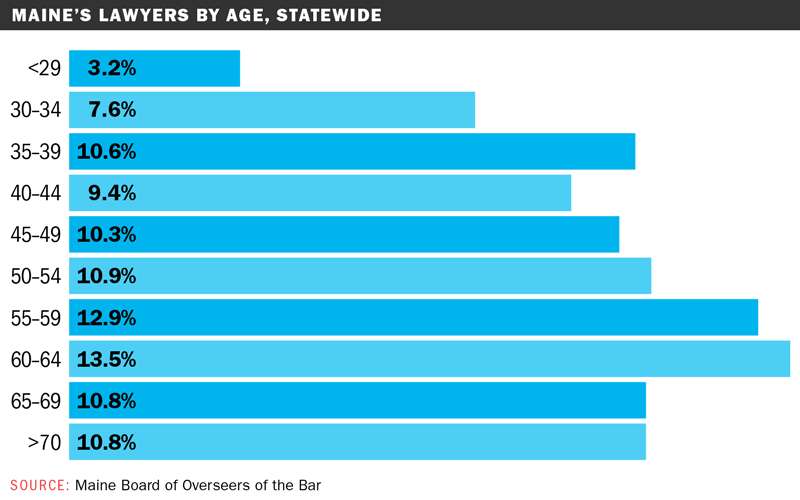

Despite the opportunities, rural Maine is experiencing a shortage of attorneys, partly due to new lawyers choosing city over small-town life and partly because of the “graying of the bar.”

“Not only do we have fewer attorneys, they’re older attorneys as well,” says Angela Armstrong, executive director of the Maine State Bar Association. “We’re losing them at a faster rate now because they are retiring, and there aren’t people who are backfilling.”

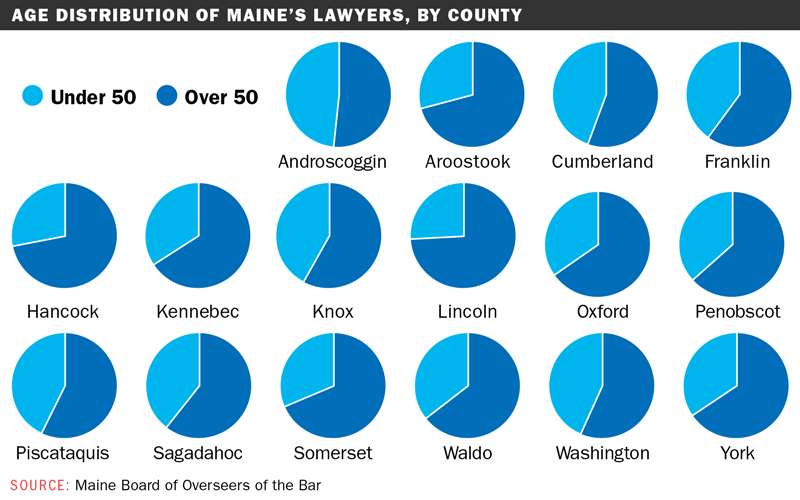

According to the most recent data from the Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar, nearly 80% of Maine’s practicing lawyers are located in just four counties: Cumberland, Kennebec, Penobscot and York, with more than half located in Cumberland County alone.

The fellowship — a collaboration between Maine Law, Maine Justice Foundation, Maine State Bar Association, and Maine Board of Overseers of the Bar — launched in 2017 to address changing bar demographics by pairing students with rural lawyers who act as mentors. The program is currently operating thanks to a three-year grant from the Betterment Fund in Bethel.

For many students, limited exposure to rural communities makes it difficult to envision what life and practice in a small Maine town would be like, which is a significant barrier to recruitment. Reflecting growing interest, the number of student and mentor applications has greatly exceeded available funding.

Through summer 2021, the program enrolled 14 students and 14 mentors throughout Maine. Several students went into practice in rural Maine upon graduation.

The choice to practice in a rural area is largely a matter of personal preference.

“No. 1 is probably that they’re from a rural area, and they want to return to a rural area to practice law,” says Rachel Reeves, the fellowship program’s director.

Reasons for not choosing a rural practice include lack of professional opportunities for a spouse or partner, lack of urban amenities and social circles, concern about the earning potential working in a smaller practice, and start-up costs for new practices in rural areas.

Supply and demand

Everett’s mentor, Adam Swanson, is originally from Presque Isle and is also a Maine Law graduate. At one time, he thought he’d practice in Portland.

“I really enjoyed Portland,” Swanson says. “I made good friends there and was pretty well settled in.”

But it was 2012 and the job market was tough. Swanson was clerking for a district court judge, who advised him to return to Aroostook County.

“He said, ‘You should go back home and hang a shingle,’” Swanson recalls.

There were plenty of attorneys in urban Maine; not so much in rural Maine. Swanson started his firm as a general practice in 2013 and had plenty of work, eventually bringing in two more attorneys, which allowed him to focus on specialty areas.

“There are many attorneys here who developed a full case load in no time at all,” says Swanson. “That speaks to supply and demand. There are plenty of people here who need attorneys and only so many attorneys to help.”

He adds, “There’s plenty of room for more.”

Finding new hires

Tonya Johnson agrees. An attorney at C.W. & H.M. Hayes PA in Dover-Foxcroft, she ran into the shortage when trying to hire.

Originally from the “no streetlight town” of Clinton, as she puts it, Johnson knew she wanted a rural practice. A 1994 graduate of Boston’s Suffolk University Law School, she joined Hayes that year. The firm, which dates to 1889, has had as many as five attorneys on staff. During Johnson’s tenure, it averaged three until 2017, when the departure of two left Johnson as the lone attorney.

“I put out an ad to hire a new lawyer and got zero applicants,” she says.

Stretched thin

The shortage means available lawyers are as busy as they want to be.

“They’re working hard,” says Armstrong. “They have that mindset of wanting to help everyone they can, but they are stretched thin because there are only so many of them in their area.”

Clients might have to look outside their communities to hire a lawyer, or might represent themselves, pro se.

“One of the impacts for clients, and the judicial system itself, is that, if clients don’t want to wait for an attorney or there isn’t one nearby, they might choose to advocate on their own behalf, and be a pro se litigant,” says Armstrong. “Clients are not necessarily getting the representation they really need by going pro se because they don’t have the legal knowledge and expertise that lawyers possess, and it taxes the court system as well.”

Another challenge is covering all sides of a conflict.

“The fewer attorneys in a small town, the more conflicts of interest you’ll run into overtime,” says Ryan Rutledge. “If there are only two attorneys in the town, usually at least one of them has a conflict on any given case. When people call my office and say, ‘I need help with this issue,’ the first thing we do is a conflict check. It is not uncommon for me to have to turn away clients because of the conflicts that exist within our smaller community.”

Rutledge is a 2019 Maine Law grad who was an inaugural Rural Practice Fellow through Maine Law’s Rural Lawyer Pilot Project. He served first with Bemis & Rossignol in Presque Isle and then with Mills, Shay, Lexier & Talbot in Skowhegan, where he accepted an associate attorney position after graduation.

Originally from Savannah, Ga., and later working with a creative branding agency in Charleston, S.C., he and his wife fell in love with Maine when they visited in 2015. Law school beckoned, and he liked the idea of a rural practice.

“I had no desire to go to law school and then cut my teeth in some 80-to-100-hour-per-week firm,” says Rutledge. “I have great quality of life. I do work quite a bit, but I have a lot of flexibility.”

Like Everett, he enjoys the ability to see cases through.

“After speaking with several colleagues from my graduating class, my understanding is that a lot of folks who went to work at bigger firms are working on big files and collaborating with other departments within the bigger firms,” says Rutledge. “How many of those attorneys end up getting to see the courtroom as the case progresses? Usually only one or two. I’m averaging three times a week in court. And that was within the first year and a half of practice.”

He adds, “It’s much more enjoyable when you get to see the fruits of your labor. You get a lot more exposure to every part of the process, and a lot more often.”

Solutions

In addition to the Rural Law Fellowship Program, Everett says he’d like to see more focus on training rural residents for the law.

“How can we eliminate barriers and open roads to people from these counties who might have significant barrier to picking up their lives and moving to Portland — people who want to come back to the area to stay, as opposed to trying to attract people who don’t stay?” he says.

Other initiatives are in the works. In 2020, the Maine State Bar Association created a rural practice initiative committee. Working with Maine Law, the committee is looking at ways to attract students to rural careers. Before the pandemic stymied the committee’s first career fair this year, intended to match students with rural firms, plenty of employers had signed on.

“It told us there are plenty of rural jobs,” says Johnson, a member of the committee.

The committee meets regularly to develop resources to help new lawyers connect with retiring rural lawyers. That includes an online community message board to facilitate conversations between retiring and incoming lawyers.

In July, the Maine Legislature enacted a bill to provide an income tax credit up to $6,000 for five years for attorneys who agree to practice for at least five years in an underserved area.

In her testimony to the Legislature, Reeves called the shortage a crisis and said it not only limits access to justice but may also limit economic activity such as business expansions, real estate transfers, and municipalities and nonprofits navigating complex regulatory requirements.

Says Rutledge, “It’s a war of attrition. We need to make sure access to justice doesn’t depend on your ZIP code.”

0 Comments