Banks embrace succession plans to smooth CEO transitions

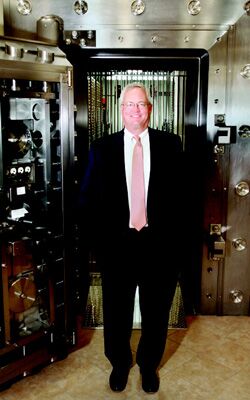

On Jan. 1, Paul Andersen will cross the threshold at Androscoggin Bank's headquarters on Lisbon Street in Lewiston as CEO, a title many assumed would be his in light of Andersen's 24-year tenure at the bank.

It wasn't an assumption held by Andersen.

"I didn't take anything for granted," says Andersen, who held the title of president and COO before formally taking the reins from outgoing CEO Steve Closson.

Neither, apparently, was it an assumption held by the bank's board of directors, which had been executing a succession plan for the bank's top post since 2007.

"The board, under Dermot Healey and now Pat Maiorino, were keeping all their options open," says Andersen. "There were several strong in-house candidates, as well as some exceptional external candidates. In the meantime, the bank was investing in people and their skill sets, including me. They continued to give me assignments that were meaningful and significant for the bank, and provided an evaluation process. The test was whether I could live up to those higher expectations. Nothing was guaranteed."

While Andersen can breathe a little easier now that the title is officially his, many other bank executives are likely to find themselves in similar situations as their boards consider who will lead their operations through the next 10 years. According to the American Bankers Association, the median age of a bank CEO is 58. That wave of baby boomers considering retirement is heightening interest in succession plans to avoid disruptive turnovers at financial institutions around the country. Adding to the pressure is increasing scrutiny from regulators who are requiring boards of directors to develop succession plans as best practices in the wake of the industry's turbulence and post-Sarbanes-Oxley atmosphere.

"I recently had five calls — four from banks in Massachusetts and one from a bank in Connecticut — asking to help with succession plans because regulators were applying pressure," says Leo McManus, a Worcester, Mass.-based consultant who specializes in helping banks develop strategic plans and succession plans for clients such as Bank of America, Deloitte Touche and community banks throughout New England. McManus presented on succession planning at the 2010 American Banking Association annual conference in October.

Likewise, Chris Pinkham, president of the Maine Bankers Association, says succession planning is the hot topic at association events. In the past few years, a half-dozen Maine banks have installed new CEOs (see, "Changing of the guard," page 19).

"The really strange thing is, they all used very different processes," he says. "Some hired from within, some looked out of state … there was no discernible pattern except it's pretty clear the 'gold watch' culture in banking no longer exists."

That culture — where a man (it was usually a man) could take an entry-level job as a teller or junior loan officer and work his way up to CEO after 35 years, put in another 10 as the chief executive and retire with his gold watch — is long gone, says Pinkham. The demands of bank leadership today are so varied and intense it's nearly impossible to stay in one bank on one track and be prepared to lead.

"It's not unusual at all for people to come from non-banking backgrounds and come into a bank through marketing or as a treasurer or CFO, or through some related organization, like the Unums of the world, or a big company like BIW, or from state government or a regulatory authority," says Pinkham. "They gain expertise elsewhere and move into banking.

"Or they have careers elsewhere and want to move back to Maine," he says. "I think that [variety] is good for the industry."

Taking a broad view

McManus says bank succession plans were pretty sporadic until the 1970s when a renewed interest in corporate planning and management started to sweep the country, fanned by management gurus such as Peter Drucker. But the plans of those 20th-century bank directors bore little resemblance to the work in front of boards today.

"The problem was, in the past, the boards took a much too narrow focus," says McManus. "They were creating a selection process rather than a development process for their people."

To be effective, a board should develop a succession plan and a strategic plan so they complement one another. If the strategic plan calls for the bank to offer an array of online banking options within three years, then the CEO better understand software and security issues around online services and the board should know how to assess a CEO candidate's competencies in those areas, says McManus. Part of the board's work in devising a succession plan is identifying existing, high-potential employees who might be destined for the executive suite and assessing the skills they need to lead, then providing opportunities for that training.

Since October 2009, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has required all publicly traded banks to develop succession plans and disclose them to their shareholders. And now the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. lists among its best practices a requirement that banks develop succession plans to identify high-potential employees and plans to develop their talent and skills.

"[Regulators] are saying they want to see a written succession plan that includes identifying who has potential [for executive] promotions and what are you doing to develop that potential," says McManus. "They are looking for security, that there are back-up plans for CEOs and other key bank personnel."

Acquiring experience

Today's top bank executives have to understand and hold competencies in technology, marketing, security and compliance issues, in addition to the traditional skills of personnel management, planning and managing a balance sheet, says Pinkham. Bigger banks could train employees by moving them around departments, exposing them to the challenges of mortgage lending and then to branch management, for instance.

That was Charles Petersen's background before coming to Biddeford Savings Bank as CEO in 2008. Earlier in his career, he spent 10 years at Bank of Boston where he held positions in eight different departments.

"That gave me a real broad experience and allowed me to develop a range of skills," he says. "That's much easier to do at a large bank and much harder at a small community bank, where there are only so many departments available for cross training."

Petersen came to the Biddeford job from a CEO position he held at a small, $80-million-in-assets bank in Vermont. It was there he discovered he loved community banking and the ability to have a measurable impact on the economic health of a town. When the bank was sold, he decided to seek a position at another small bank and not return to the larger institutions where he'd spent the bulk of his banking career.

He said his unfamiliarity with Biddeford prompted some reservations among the Biddeford Savings directors, but his experience in leadership positions at larger banks, coupled with his CEO experience in Vermont and engagement in community markets, won them over.

"I believe I had the right skills and abilities to interact with the community and lead the company forward," he says. "Perhaps it was a little harder than if I'd been from the area, but I think it's worked out well."

Ironically, one of Petersen's first duties was to develop a succession plan at Biddeford Savings.

"Regulators just expect to see it," he says, a point he made earlier this year at the Independent Community Bankers of America conference where he presented on succession planning. "You need to be prepared."

Getting ducks in a row

In accordance with a succession plan, smaller banks will often seek specialized training for their high-potential employees to give them the training and experience they can't get on the job. That was the case with Andersen of Androscoggin Bank, who went to the Stonier National Graduate School of Banking for intenisive training in accounting, financial management, marketing and other topics important to a bank CEO. The program required a three-year commitment. Andersen, the first Androscoggin Bank employee to attend the institute since Hanson Ray, the CEO who preceded Closson, graduated in 2006.

That training was part of the succession plan the Androscoggin Bank board began implementing as it prepared to replace Closson, who had held the CEO title since 1991. Closson says by identifying Andersen as a strong contender for the job early in the process, the board created a sequence of events that not only prepared and tested Andersen, but also gave attention to other expected changes in the bank's governance.

"It wasn't just my retirement, but the retirement of three directors and Paul's changing role. … We were planning for all those people and what their departures would mean from an organizational point of view and a personal point of view," says Closson. Key to that was a strong relationship between the two men based on mutual respect. Both had seen CEO successions go horribly wrong at other banks, where power grabs divided the staff and boards.

Andersen had been COO since 2008, then in 2010 added executive vice president to his title and at the beginning of this year, president. Closson says Andersen has been running the day-to-day operations of the bank for the past couple of years, all of which created the impression that he was the heir apparent.

"And that creates an air of confidence and continuity among the staff, the directors and the customers, that there's nothing to worry about. The transition will be seamless. That's what you want," he says.

Comments