Maine’s colleges and universities find new, innovative areas for growth

With the cost of tuition, room and board tipping past $250,000 for a bachelor’s degree — two or three times the cost of 25 years ago — higher education might be considered one of Maine’s growth industries.

Bowdoin College has seen its endowment blossom from $465 million in 2000 to $1.63 billion today. Colby College is on track to raise $750 million in the largest fundraising campaign ever undertaken by a liberal arts college, according to the school. Bates College is raising $300 million.

Money is flowing at record levels into the state’s public university system too. The University of Maine Orono last year received gifts and pledges of $37 million, the most ever.

Maine’s colleges and universities have beefed up their offerings. University of New England has Maine’s only dental school and the only medical school, the College of Osteopathic Medicine. UMaine distinguishes itself with the state’s only college of engineering and only law school. UNE and Husson University have the state’s only pharmacy colleges. Schools like College of the Atlantic and Unity College have carved out specialties in environmental studies. Husson and Thomas College have developed strong business schools.

Increasingly, Maine’s 28 accredited colleges and universities are also cultivating a different kind of growth, in the businesses and communities outside the campus gates.

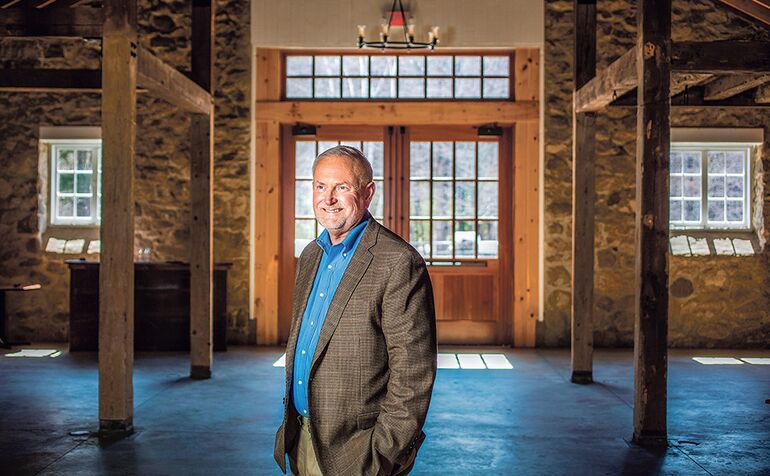

“The traditional growth mindset of higher education has been challenged,” says James Dlugos, president of Saint Joseph’s College in Standish. Rising tuition and economic factors like the most recent recession have created more public scrutiny about the value of a traditional, full-time college education. With declining enrollments across the country, colleges are under more pressure than ever to deliver results.

“The message that’s been sent to us [from the public] is, ‘We don’t have to do this,” Dlugos says.

One of the ways Saint Joseph’s has responded to that message is the 2018 launch of the Institute for Local Food Systems Innovation, an incubator — literally — for developing new, sustainable practices that may benefit the state’s farms and food producers.

When construction is complete, probably in 2021, the 29-acre institute will comprise a hydroponic greenhouse, a traditional crop and livestock farm, a commercial kitchen, and room for events and classes. Supported by $4 million in federal and private seed funds, the institute will offer student programming, workforce training in fields such as food processing and agritourism, and facilities for local food entrepreneurs.

Dlugos believes the institute makes good use of a major asset — the college’s 470 acres of land along Sebago Lake — while making educational sense for students and economic sense for the state.

“It’s good for the Lakes Region, it’s good for Maine,” he says. “As we build out enterprises like this, they all produce jobs and attract people to the state.”

David A. Greene, president of Colby College, hopes for a similar result in Waterville.

Funded partly by its capital campaign, the college is investing $100 million to spur commercial redevelopment in the downtown area, two miles from the college’s bucolic campus atop Mayflower Hill.

The revitalization effort, begun in 2014, has already led to four projects on Main Street: renovation of the Haines Building, now home to technology services provider CGI Inc.; the newly constructed Bill and Joan Alfond Main Street Commons, which houses 200 students and a branch of Camden National Bank; a proposed downtown art gallery; and a 50-room hotel, expected to break ground this summer and open in 2020.

Greene believes Colby’s investment in Waterville is a “moral obligation” stemming from the community’s longstanding support of the college. That includes the gift of Mayflower Hill, deeded to Colby in 1930 after the city raised $107,000 to purchase the property.

“We can never forget that,” he says. “Now it’s time for us to step up.”

Back at Saint Joseph’s, Dlugos applauds Colby’s work, and feels it typifies how Maine colleges today are giving back to their communities.

“We don’t want to all be doing the same thing,” he says. “But this place-focused energy is similar among us.”

Even the University of Southern Maine’s planned name change may symbolize a return, of sorts, to local roots. The new name — the University of Maine at Portland — is designed to play up the appeal of a community, while appealing to out-of-state students.

In order to remain relevant, Greene says, Maine colleges must continue building open, collaborative relationships with their communities.

“The cloistered walls of our academic institutions are beautiful,” he says, “but they have to be permeable.”

0 Comments