What looks like a mini-castle or Revolution-era fort on the Maine landscape is, frequently, the local library. Until the late 19th century, most U.S. libraries operated on a subscription model, catering to the better-educated and deeper-pocketed. One man credited with changing that was Andrew Carnegie, who made his fortune in steel and spent some of it on the housing of books.

Between 1886 and 1919, Carnegie financed (or co-financed) the construction of around 1,700 libraries across the country, 21 of them in Maine, on the condition that the new cathedrals of literacy be open to the public and supported by community tax dollars. Many were in fact cathedrals, at least in miniature. Architects reached back to the Renaissance, Middle Ages and Classical eras for their blueprints, dotting Maine’s towns and villages with little bastions of knowledge. The state is now home to around 260 public libraries — possibly the most per capita of any state in the country — plus more than 30 academic libraries and at least 42 “special” libraries. In an era of cultural warfare and reduced funding for education, none have escaped budget stresses and painful decisions about cutting staff and programming.

Most Maine libraries are locally funded, as either nonprofits or municipal departments. While that shields them from the immediate impact of Trump administration budget cuts, it leaves them vulnerable to local cost pressures. Some crisis management training came with the COVID pandemic. Libraries offered curbside and virtual lending, and stepped up “library of things” lending of equipment such as power washers, trombones or telescopes.

“It’s hyperlocal,’’ says Amy Wisehart, who runs the Northeast Harbor Library and recently completed a one-year term as president of the Maine Library Association. “Libraries are always adjusting to the realities of their communities.”

The financial squeeze, however, is here to stay. It may be cheaper for you or me to download a digital book, but it’s more expensive for libraries: one license can cost up to $90. The Trump administration’s efforts to dismantle a federal library-support agency further complicate matters. Despite the financial strains, Wisehart knows of none in Maine that are threatened with closure. What is more likely, she says, is the curtailment of opening hours and services.

Photo / Jim Neuger

ODDFELLOWSHIP: The West Paris library’s director, Brenda Lynn Gould, trained as an electrical engineer, and has experience as an herbalist and shepherd on her resume. Here, she leafs through an album depicting past grand masters of the West Paris branch of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, which met in a lodge — now, like the library, a registered historic landmark — across the street into the 1980s.

Photo / Jim Neuger

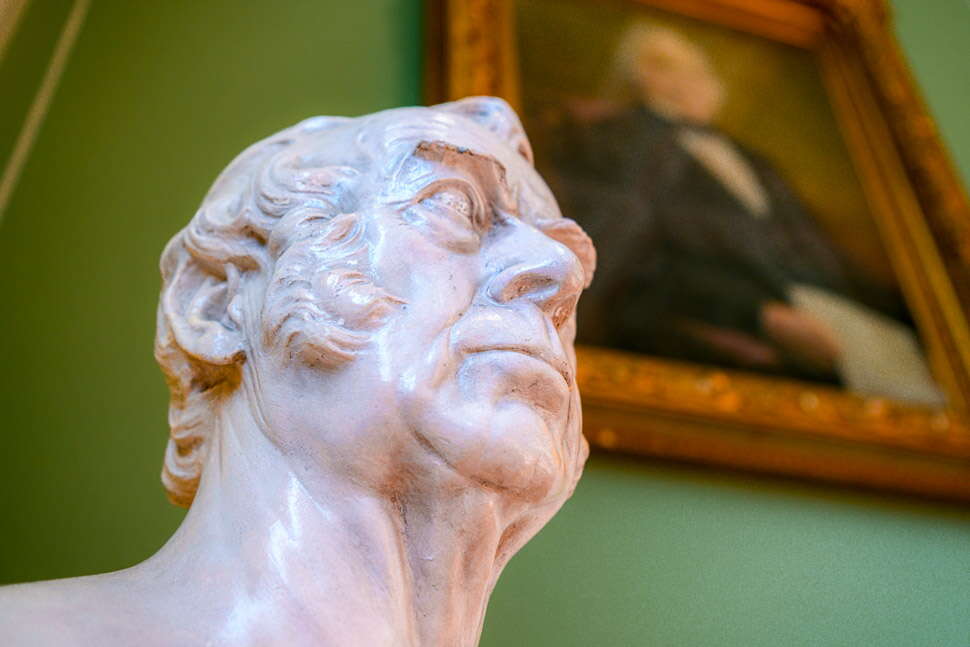

NEW AND OLD: From “The Banned Books Club” to “The Secret History of Bigfoot,” the Lithgow Public Library in Augusta — like its peers up and down the state — devotes part of its budget to keeping up on the latest reading habits. (Book banning, by the way, is more of an issue for schools than community libraries in Maine.) Historic preservation is equally important. Venerable tomes of yesteryear on the Augusta shelves include “Picturesque America,” an illustrated homage published in 1874. Among the library’s founding spirits were James Ware Bradbury (portrait) and Reuel Williams (bust). Both represented Maine in the U.S. Senate in the 1800s. Bradbury made a key financial contribution to the construction of the original building in 1896, as did Williams’s heirs. Carnegie wrote a check too.

Photo / Jim Neuger

MAPPA MUNDI: Back in the pre-GPS era, people got around with printed maps. Some of the rarest and most artistic of these visual guides to cities, countries, continents and the cosmos have found their way into the Osher Map Library on the campus of the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Some of the Osher artifacts go back to the 1400s. Revolving exhibitions showcase the library’s collections, including Elizabeth Shurtleff’s “Star Map” from 1926, presented here by Libby Bischof, the library’s executive director. Traveling further into the zodiac, the display at the rear features translucent astronomical drawings published in Brussels in 1858.

Photo / Jim Neuger

STYLE ICON: Above, the Waterville Public Library, with Carnegie as the main financial backer, was built in an early Middle Ages revivalist style known as Richardsonian Romanesque. The namesake architect, Henry Richardson, pioneered the pastiche style — featuring rounded arches on squat columns and lofty towers — in the 1870s, spawning imitators including William Miller, Waterville’s designer. “This is Your Library,” proclaimed a 1955 advertisement for an open house to mark the building’s 50th anniversary. “Do you use its Free Services?” Moving in the other direction in time, every library has a pre-history. Waterville’s began in 1801, with the purchase of 117 books from a Boston bookseller for $162.65, benefiting from a 10% discount, according to the Town Line website.

Photo / Jim Neuger

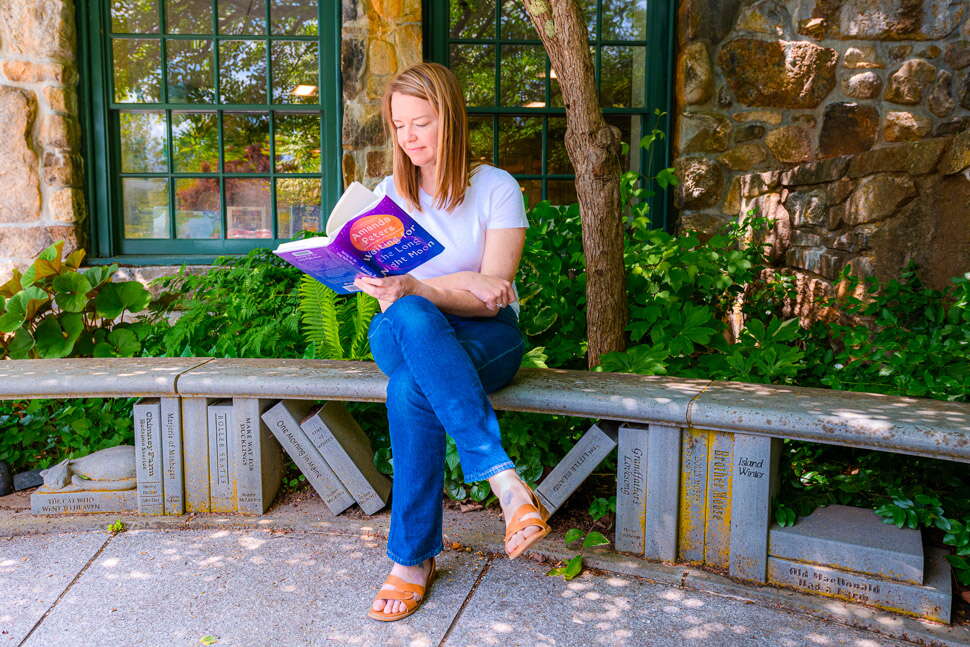

BOOKENDS: One of the educational design elements at the Camden Public Library is a children’s garden where reading is, literally, the foundation of all knowledge. Here, Kristy Kilfoyle, the library’s executive director, peruses a modern work of short fiction while seated on a bench supported by granite-hewn versions of Pine Tree State faves such as “One Morning in Maine” by Robert McCloskey. Libraries are also repositories of local history, with everything from yellowed newspaper clippings and tax assessor’s maps to searchable genealogical archives. A highlight of Camden’s collection is a diorama of the town’s harbor circa 1920. (At upper right is the Megunticook River waterfall, fortified by a 200-year-old dam which town residents voted to remove in a June referendum.)

Photo / Jim Neuger

MONEY FROM AWAY: It’s a mistake to whiz past the Ogunquit Memorial Library, catering to locals and tourists alike since 1898. Also in the Romanesque mode, the petit castle owes its existence to Ogunquit’s status as a magnet for seasonal visitors. Two regulars in late 19th-century summers, lawyer George and his wife Nannie Conarroe from Philadelphia, were so enamored of the coastal enclave that, after George died, Nannie donated family money to build the library and 1,500 family books to stock it. As if that weren’t sufficiently charitable, Nannie set up a family trust fund that provides income for the library to this day.

Photo / Jim Neuger

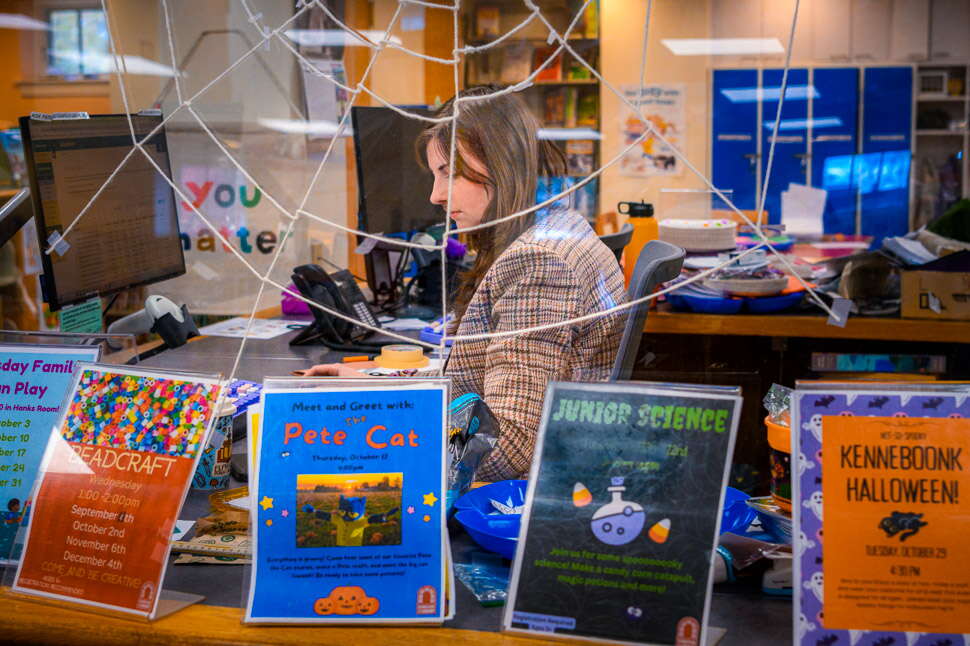

KITTEN KA-BOOK-LE: Meet Otis, a 10-year-old charcoal gray temporary inhabitant of the Kennebunk Free Library. In an adoption program in collaboration with the local Animal Welfare Society, Otis and best pal Levi — and many more felines — have bunked amidst Kennebunk’s books before finding their forever home. Mostly, libraries serve two-legged patrons. All have busy programs for young children and teens, with activities and decorations changing with the seasons — as with the spidery Halloween motifs gracing the workstation of Emmaline Arena-Bruce, a tech educator and teen programming librarian in Kennebunk.

Photo / Jim Neuger

West Paris might seem typical of Maine’s pint-sized towns — population 1,776, with 13 births, 16 marriages, 17 deaths and two police calls for disorderly conduct in 2024 — but its library is anything but. Like a medieval tiny home, it was built in 1926 with local fieldstone and still sports the original oak door with iron hinges.

Photo / Jim Neuger

West Paris might seem typical of Maine’s pint-sized towns — population 1,776, with 13 births, 16 marriages, 17 deaths and two police calls for disorderly conduct in 2024 — but its library is anything but. Like a medieval tiny home, it was built in 1926 with local fieldstone and still sports the original oak door with iron hinges.

0 Comments