Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- November 17,2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- September 8, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

The Damariscotta region is rich in all things oyster

The Maine Oyster Trail, a searchable online tool for finding oyster farms, shacks and restaurants, lists oyster farms from Sorrento to Kittery, but the majority of Maine’s harvest comes from the Damariscotta River.

Oysters are so prevalent on the Damariscotta River that heaps of shells still exist from when indigenous people created the middens over the course of a thousand years between 2,200 and 1,000 years ago.

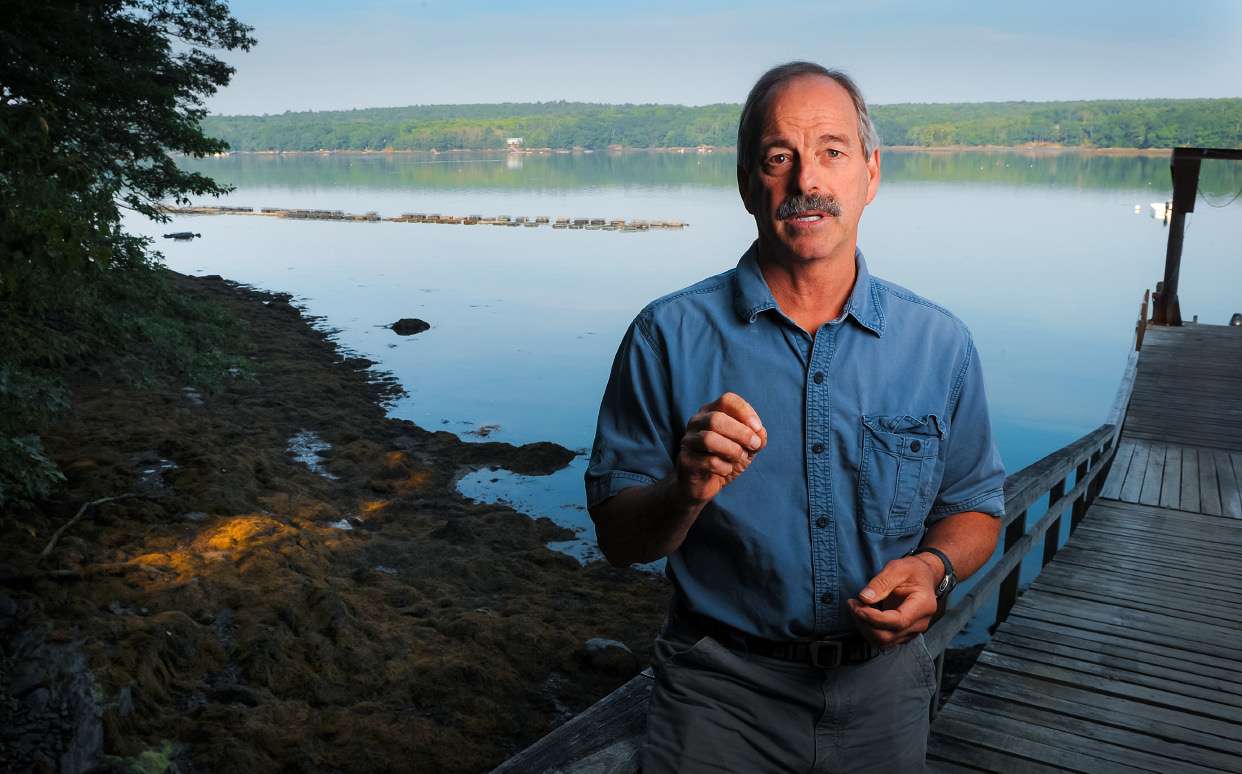

“There’s a several-thousand-year history here,” says Bill Mook, who founded Mook Sea Farm in Walpole in 1985. “The foundation is here. The oyster population is a natural one here and it’s only growing.”

Mook pointed to the oyster cruises, kayak tours and restaurants that have all centered on the oyster industry along the Damariscotta River area.

“Maine historically has a working coastline. Oyster farms won’t in any way replace lobstering, but it’s a great way to diversify the waterfront economy,” Mook says.

The value of the oyster harvest was $7 million last year, down from $9.7 million the previous year, reflecting the pressures the pandemic put on seafood prices and consumption, according to the Maine Department of Marine Resources.

A total of 10 million oysters were harvested in the state in 2020, with more than 6 million alone coming from the Damariscotta River.

“The Damariscotta area is the oyster holy quest. The Damariscotta River is where most of the oysters come from,” says Brendan Parson, owner of Shuck Station oyster restaurant in Newcastle and Blackstone Point Oyster Farm on the Damariscotta River.

This year, as tourists weary of the pandemic flooded into Maine, saw a jump in both demand and supply, harvesters say.

“This year was absolutely record setting. You couldn’t grow or harvest fast enough to keep up with demand,” Barbara Scully, who sold Glidden Point Oyster Farms in 2016 and now operates Scully Sea Products. “We’ve seen success this year at a level we’ve never seen before. There’s more market demand than the industry can produce.”

Oyster production is small compared to the iconic Maine lobster industry, which caught 96 million pounds worth more than $400 million, according to the Maine Department of Marine Resources.

The lobster industry faces threats from global warming, federal regulations on gear due to conservation efforts for right whales, proposed wind mill projects and labor shortages that have made it harder to find sternmen.

In many ways, oyster farms provide a more stable environment, growers say.

“It’s an exciting time to be part of aquaculture — when other parts of fisheries are less stable — to help keep the overall working waterfront more vibrant,” Parsons says.

Parson’s Shuck Station restaurant attracts a mix of oyster farmers themselves, as well as locals and tourists. He tries to bring an educational element to serving oysters. The restaurant provides maps of the river with each oyster farm represented to show exactly what the customer is eating and where it was harvested.

Wine makers use the term “terroir” to encompass a sense of place — all the factors that go into producing wine grapes, such as soil, elevation, climate. Likewise, oyster harvesters talk about the “merroir,” or sense of the sea and the environment that produces oysters. The merroir of different places within the Damariscotta River can produce different flavors and different firmness of oysters, harvesters say.

“The Damariscotta River happens to be one of the most productive estuaries. It’s ground zero on where oyster aquaculture started,” says Scully.

“The tourists looking for oysters and oyster farms can find everything here,” Scully says. “It’s the perfect place for people to learn about and love oysters. For a tourist, they can see multiple things in one place.”

The pioneers in the Damariscotta River area, such as Mook and Scully, who started oyster farms in the 1980s, proved the skeptics wrong who say it was too cold in midcoast Maine to grow oysters.

Mook rears Eastern oysters from egg to adult size, and his hatchery produces more than 120 million juvenile oysters, or seeds, a year for sale to other oyster growers from North Carolina to Maine.

“The businesses that have been here for years, who were pioneers along with me 30 to 35 years ago, they’re not going away. We’ve all seen enough success financially to show that it’s a proven industry,” Scully says.

Oyster farm has grown into enough of an industry that it has served as a draw of young talent to the region.

“The thing I find gratifying is all the young people who have moved to Maine to grow oysters. They are passionate, well-educated, hard working. To be an oyster farmer, you are an environmentalist. You can’t do it without a healthy environment,” Mook says.

“A lot of people don’t like to look at oyster farms and have a lot of money to try to restrict our growth. But they miss that the oysters are clearing the water and increasing biodiversity,” he adds.

Scully added that aquaculture and oyster harvesting, in particular, has exploded along Maine’s whole coast, so the concentration in the Damariscotta region will become more diffuse.

“The future is not just along the Damariscotta River. There are small oyster companies in Casco Bay, Harpswell, Downeast. They’re going to be everywhere,” Scully says.

“It’s an industry you’re proud to be a part of. It’s a healthy industry. It’s an environmental industry. It’s good for towns and committees to get behind. There’s all kinds of room for growth,” Scully says.

Scully says the oyster industry is good because harvesters of all sizes can find success, adding “you don’t have to be a giant of industry to be successful.”

Boe Marsh, owner of Community Shellfish in Bremen, says the Damariscotta River is very special because it has the Great Salt Bay above it as the engine for food for the oysters.

“It’s warm, shallow, and has lots of food and oxygen.” Marsh says.

“The midcoast, in general, is a great place to grow oysters. The Damariscotta and Medomack Rivers create some of the best oyster growing areas in the world,” Marsh says.

“The whole area of aquaculture is a newish industry. We need, statewide, more promotion of the Maine oyster in the national and international scene,” Marsh says. “If you grow a lot of oysters and can’t sell them for enough, then it’s all for naught. It needs to be continually promoted and marketed outside.

“Aquaculture gives the working waterfront a new role, more opportunities and supplemental ways for fishermen to make money.”

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

0 Comments