To make projects work, savvy developers tap a range of tax incentives

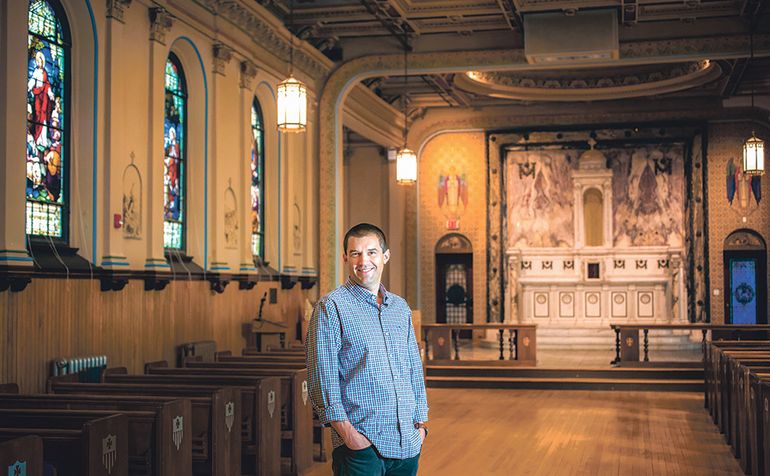

Photo / Tim Greenway

Kevin Bunker, founding principal of Developers Collaborative, in the three-story chapel in the Motherhouse at Baxter Woods in Portland.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Kevin Bunker, founding principal of Developers Collaborative, in the three-story chapel in the Motherhouse at Baxter Woods in Portland.

Developers are tapping into increasingly creative ways to finance projects in Maine.

Tax incentives, tax credits and Opportunity Zones are just a few of the many financing tools designed to attract capital and achieve a public purpose by arranging partnerships and getting players — developers, investors, financiers, municipalities — to talk about deals they wouldn’t have otherwise considered. The programs are designed to encourage private investment in low-income areas through tax advantages.

Incentives have helped an array of well-known projects get from the drawing board to completion. A vacant commercial site in Livermore Falls was redeveloped with help from New Market Tax Credits. Tax Increment Financing is used in municipalities statewide to provide incentives to business owners. And federal Opportunity Zone tax incentives are creating interest in Maine’s 32 designated areas.

“There’s laundry list of programs out there,” says John Egan, chief investment officer with Coastal Enterprises Inc. in Brunswick. “The motive is to essentially drive private market investment into projects or areas or both, where they might not otherwise look to invest.”

How it works

Let’s say a developer plans to purchase a historic building for $1 million and to invest an additional $2 million to redevelop it for mixed use.

It’s a registered historic building and the planned improvements are so-called “qualified historic costs” as defined by the Internal Revenue Service. So the project qualifies for a federal historic tax credit of 20% of the $2 million, or $400,000; and a state historic tax credit of 25% on the $2 million, or $500,000. That’s a total offset of approximately $900,000 (minus transaction costs) on tax liability. That promise of future credits, allocated over a multi-year timeframe, is an advantage to the developer as he takes the next step of getting up-front financing for the project.

So he goes to the bank for that $2 million.

The bank agrees to lend him $1.5 million; that amount is based on projected revenues, like rental income. Where to get the remaining money? Because the property is located in a designated Opportunity Zone — an investment program created by the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 to connect private capital with low-income communities — the developer is able to source the rest of the money from investors attracted to the program’s promise to reduce capital gains taxes on other deals they’ve made. And if the investor remains in the project for 10 years or more, he can take his gain on the increased value of that investment tax-free.

That’s an illustration of how developers can piece together various finance tools, including tax-advantage programs like historic tax credits and opportunity zones, for their projects, says Kevin Mattson, CEO of Dirigo Capital Advisors in Topsham.

Referring to those tools as a “capital stack,” Mattson explains the example above broadly illustrates how Dirigo Capital and its partner, Capital Area Properties of Gardiner, built the financing they needed for the redevelopment of a former Odd Fellows Hall at 333-339 Water St. in Augusta. The space will be used for retail and residential use.

“It’s not usually just one incentive,” says Mattson. “I look at it like an onion. You have to have many layers to make it work economically.”

There’s also simple arithmetic involved. The project must generate enough return to make the investment attractive to financial institutions.

“If you’re trying to do a project in Aroostook County, it’s the same cost to build as in Portland, but the rate of return you get, say, from rents, is much lower,” says Mattson. “To offset that, you add in Tax Increment Financing, historic tax credits and in some cases low-income housing credits. Sometimes developers will layer on four or five programs to make the numbers work.”

Transforming communities

The Maine State Rehabilitation Tax Credit and the federal historic preservation tax incentive have been two of Maine’s most successful tools for fostering redevelopment. Greg Paxton, executive director of Maine Preservation in Yarmouth, says he’s seen the programs help transform dilapidated communities.

“From a real estate perspective, these are often the buildings people call eyesores,” Paxton says. “Often these buildings not only look bad, they’re hurting the real estate market around them. By being rehabilitated, and becoming landmarks in many cases, they’re now helping the market, inspiring others to do similar projects and bringing in people to live and work.”

The state credits have been used on 95 rehabilitation projects since 2008, delivering $856 million in economic impact, 1,800 housing units and 9,820 new jobs. They’ve also generated $99.3 million in tax revenue.

“The simple fact is, without the tax credits, virtually none of the projects would have been done,” says Paxton.

Do credits detract from tax base?

The crux of a longtime debate about economic development is whether developers are dipping into the tax base. Ultimately, incentives offer ways around paying taxes or reducing the tax burden.

“But the projects are generating economic activity, they’re generating property tax, and in commercial deals they generate payroll taxes that go with the jobs being introduced,” Egan says. “Plus, many of these properties, like schools and churches, were never on the tax rolls. So there’s a big boost to communities.”

In the case of historic tax credits, studies show increased property tax revenues generated by the historic projects exceed the annual cost of the program.

“All taxes collected in 2016 at the state and local level exceed the amount of tax credits issued,” says Paxton. “By 2022, all the money the state has invested in this program will have been paid back to the citizens of Maine by virtue of the increased taxes to be collected. For many of these buildings, the average property tax assessment increased by 350% as a result of these projects.”

“If you ask the top 10 housing developers in Maine if they could have redeveloped a mill, say, in Biddeford or Lewiston without the Maine historic tax credit, they would say ‘No,’” says Mattson. “It’s a game-changer.”

Combining programs

Kevin Bunker, founder of Developers Collaborative in Portland, has used historic tax credits on numerous projects. He’s also combined various programs.

“I’m attracted to projects that are community-based and hard to figure out,” says Bunker. “That sends me to use all these tools, to layer and stack them and make them interact properly with one another. That’s a whole science.”

In 2012, Developers Collaborative combined federal New Markets Tax Credits and historic tax credits as part of its stack to purchase and redevelop the Lamb Block, a historic building in Livermore Falls redeveloped for mixed-use commercial space.

New Markets Tax Credits allow investors to provide capital and in return claim federal tax credits for up to 39% of their investment. The credits offer a source of cheap or free equity developers wouldn’t otherwise have, allowing them to do projects that aren’t otherwise financially feasible, Bunker says.

The Lamb Block had an overall price tag of $2.3 million. With the help of CEI Capital Management, the project received a New Markets credit that allowed it to receive a subsidized loan. Developers Collaborative gave the credit to its lender, Bangor Savings Bank, in exchange for a $960,000 loan at a low interest rate of 2%, versus what would have been a 4% interest rate. At the higher rate, Developers Collaborative wouldn’t have been able to borrow what it needed for the project; its borrowing capacity was limited by the projected rental income.

The project also received a federal historic tax credit of $410,000, state historic credit of $442,000, $400,000 from the now-defunct Communities for Maine’s Future bond program, and Bunker’s own deferred developer’s fee of $154,000.

“If I didn’t have all those things, I’d have no project,” Bunker says. “We got the tenant. We got them to a rate they could afford. We couldn’t push the rent any higher. So we wouldn’t have been able to get any more debt.”

U.S. Treasury Department’s New Markets Tax Credit program and Maine’s New Markets Capital Investment program, administered by Finance Authority of Maine, target low-income communities.

The programs have been used extensively in Maine, says Charles Spies, CEO of CEI Capital Management, which helps deploy the credits. The net effect is a return of more than $3 in economic activity — spending on things like construction, plus increased property taxes — for every $1 in tax credit, he says.

There are a variety of other finance tools. A commonly used program is the low-income housing credit, issued by the U.S. Treasury and allocated by the Maine State Housing Authority.

“It’s very successful and has been transformational in many communities,” CEI’s John Egan says.

Tax Increment Financing, administered by municipalities, subsidizes redevelopment, infrastructure and other community-improvement projects. It’s proven a powerful tool for attracting development, Egan says. For example, a developer turning an old school into apartments in a TIF district might be able to negotiate a $12,000 property tax bill instead of $24,000.

“That extra $12,000 allows the developer to negotiate more easily the amount of debt he has to seek, or to turn that tax savings into another capital source,” Egan explains.

Opportunity Zones

Still untested is the Opportunity Zone program: “the new kid on the block,” says Spies.

“That’s still maturing in terms of how it will be used,” Spies says.

Designed to drive capital into economically distressed areas, the program allows individuals to invest capital gains in opportunity zone projects, thus deferring the gain and a portion of associated capital gains taxation. Any gain made on an Opportunity Zone investment that remains in the project for a decade or longer will see no capital gains tax.

Mattson views the program with optimism.

“There’s trillions of dollars of money that has accumulated over the last 10 years in the incredible run of the stock market,” says Mattson. “An investor looking to sell a stock, that maybe increased 400% in the last 10 years, might look at Opportunity Zones as a place to put the money to shelter it. It’s a very creative idea.”

In the end, says Mattson, the developer pieces together programs as a function of the economics of the project.

“That’s different in Portland versus Caribou,” he says. “If you’re doing a project in Caribou, you might have lower income yield, but everything else is the same as Portland — taxes, insurance, construction costs. In Caribou, you might only be able to generate $750,000 of bank debt, because you have less income. So you have to think of ways to make up your capital stack. These incentives are really important. If I were in Millinocket and I saw an Opportunity Zone, I would think, ‘Wow, this changes everything.’”

0 Comments