A biomedical program trains future researchers, but federal funding cuts jeopardize its outlook

Photo / Courtesy MDI Bio Lab

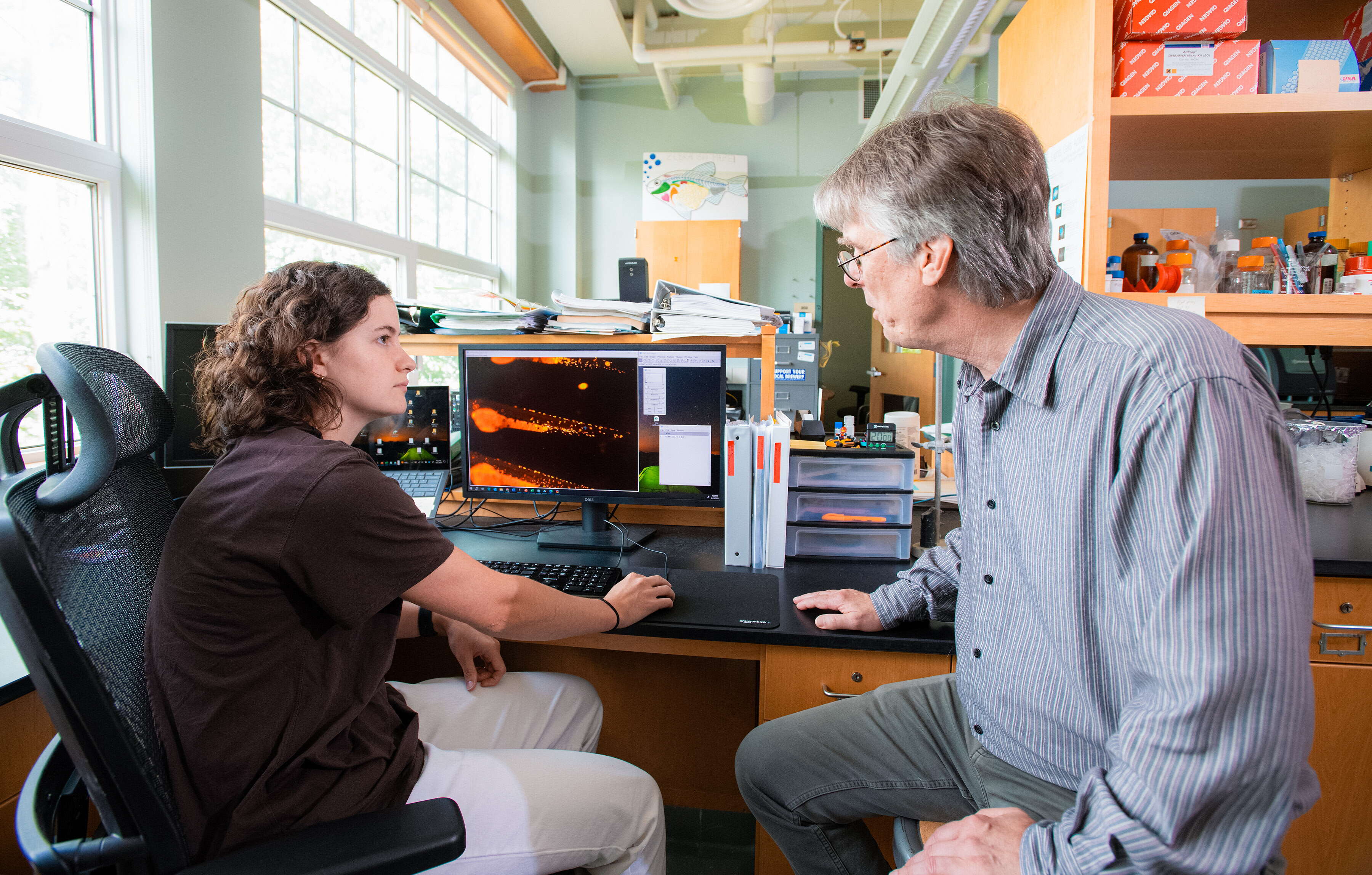

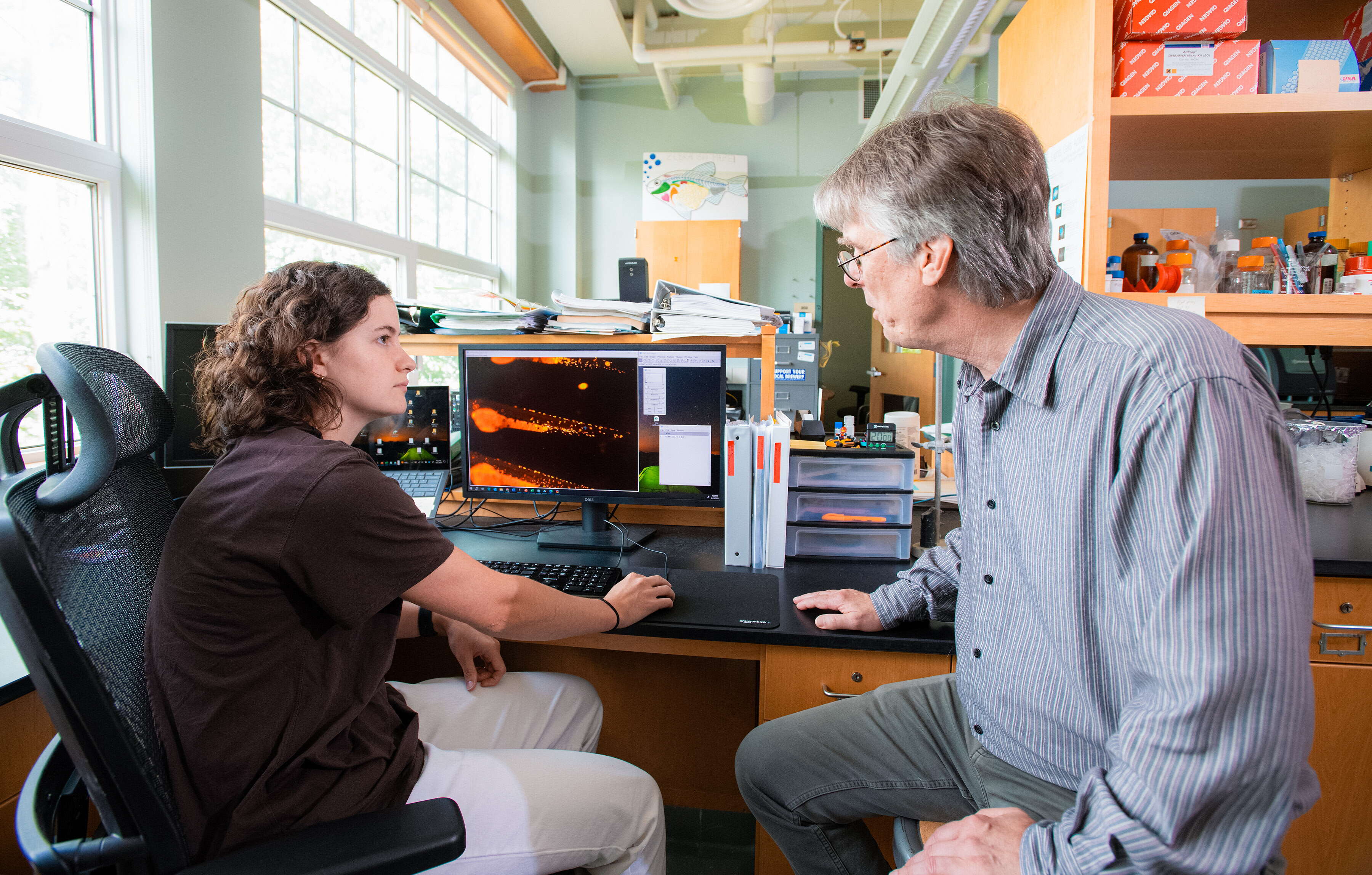

Sam Cousins, says real-world research prepared him for future job and academic opportunities.

Photo / Courtesy MDI Bio Lab

Sam Cousins, says real-world research prepared him for future job and academic opportunities.

A few years after graduating from high school in 2020, Sam Cousins enrolled at Southern Maine Community College to study biotechnology.

A year-and-a-half in, the Gorham native took take a weeklong course, at Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, that provided real-world research into regeneration — a burgeoning study of how certain cells can rebuild damaged tissue.

Cousins studied the process in a tiny worm, putting into practice materials and processes that he had learned at SMCC.

“It was my first taste of doing that type of research,” he says.

Last summer, he enrolled in a 10-week program at the lab, allowing him to continue the work as a full-time job, deepening his skills and resume and establishing contacts. Both courses were funded by a program called Maine INBRE, short for Maine IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence. (IDeA is an acronym for Institutional Development Award.)

Working together

Led by the Bar Harbor bio lab, Maine INBRE is a consortium of 17 education and research institutions that collaborate to strengthen Maine’s competitiveness in biomedical and biotech research, feed students to biomedical and biotech careers and improve research infrastructure.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence program began at the national level in 2001, initially providing planning grants and later establishing biomedical research networks in 23 mostly rural states to make them competitive in the larger research world.

In Maine, the network began as the Biomedical Research Infrastructure Network and became INBRE in 2004.

“For a state like Maine with a small population and a vast geography, it’s our willingness to work together that makes us competitive in the larger research world and that helps us to punch above our weight,” Hermann Haller, the lab’s president, said last summer, when he announced the latest $19.4 million NIH funding renewal.

Despite considerable uncertainty about the future of that funding, the program continues this summer with the latest convening of Maine undergraduates who, like Cousins, are undertaking paid 10-week fellowships at the lab and at some of the network institutions including Bates, Bowdoin and Colby colleges, UMaine, the University of New England and MaineHealth Institute for Research.

Career advancement

For thousands of students and scores of faculty members across the 17 institutions, the program has been instrumental for leveling up careers.

For Cousins, the INBRE experience prepared him to return to the lab this summer through a different program. At 22, he graduated from SMCC last winter, continues to pursue his research and is overseeing other students and exploring future options.

The INBRE program was invaluable, he says. It allowed him to work on real-world research under the supervision of lab scientists, using sophisticated gene editing and imaging technology and learning techniques for working with the tiny worms that prepare him for future job and academic opportunities.

Bonus? “Giving me access to the community and the people here is almost the biggest thing that INBRE did for me,” he says. “These scientists are at the forefront of their field, giving me the ability to ask them questions, further my education and form a network.”

‘Research bug’

“INBRE” is a clunky acronym. But the idea is to expand Maine’s biomedical research capacity, by providing money that supports workforce and infrastructure development and high-level research.

A central philosophy is to engage undergraduates so they catch “the research bug,” as James Coffman, Maine INBRE’s director, says.

The network connects thousands of undergraduates with genuine biomedical research experiences and access to state-of-the-art equipment through intensive courses, workshops and paid fellowships, helping to build a technically skilled biomedical workforce for Maine.

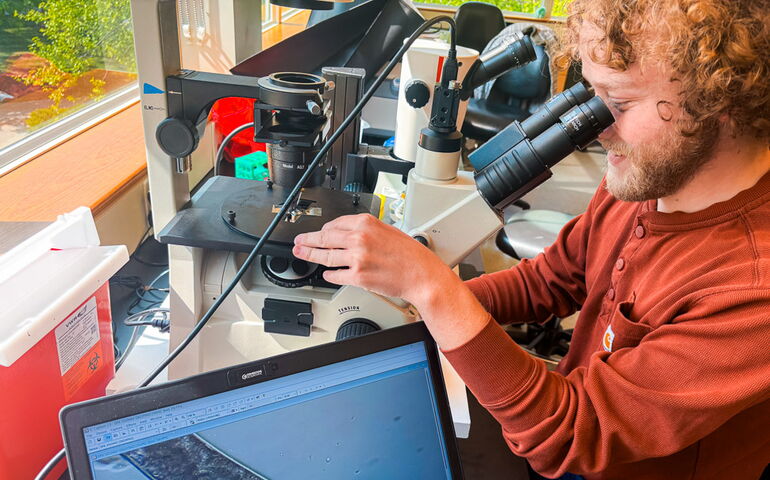

It supports early-career bioscience faculty with research grants, lab equipment, software and related services needed to compete for larger federal grants. And it invests in shared, state-of-the-art science infrastructure, from advanced gene editing and data science systems to leading-edge 3D microscopy, building overall research capacity.

Shared resources

As a collaboration across institutions, it builds in shared resources for scientists, faculty and students, such as MDIBL’s microscopy facility and data science program and a slew of scientific facilities and services at other participating institutions. An instrument exchange program promotes cost-effective research. Faculty and students at participating institutions can participate in research opportunities through various means, including fellowships, research equipment, research supplies, travel to scientific meetings, renovation of laboratory space and tuition.

INBRE funds are organized and administered via four “cores:” administrative, data science, collaborative research resources and developmental research projects. The collaborative research resources include the light microscopy facility at MDIBL, which provides access to biomedical scientists to complex microscopes and sophisticated imaging technologies — considered an essential piece of the research puzzle given the accelerating rate of imaging technology development, turnover and high costs that make it difficult for individual research labs to afford, master and maintain.

A data science core serves as a statewide resource for Maine INBRE by providing essential consulting and training in large, complex data sets.

In the absence of core programs, expertise comes and goes with membership of specific research groups, says Joel Graber a senior staff scientist at MDIBL and co-director of the data science core.

Before INBRE, there was some collaboration between Maine biomedical institutions. “But it was not nearly as strong since this funding came into play,” says Coffman.

Institutions have their own priorities and cultures. “Some institution have huge amounts of resources and funding,” he continues. “Others are struggling financially. Some have students from all over the country. Others have students from rural Maine who have never been to college before. One objective is to harmonize all of that and make sure the research resources are accessible to everyone in the network.”

Competitive edge

A good way to develop research capacity is to engage undergraduates.

“Not just train them, but engage them,” says Coffman. “If you get undergraduates involved in a research program, actually doing the research themselves, that’s the way to hook them.”

Graber has seen students go on to graduate school or careers in biology and biotechnology after their exposure to INBRE programs.

“The primary benefits of the program are the resources and effort it has provided for us to train the next generation of scientists,” Graber says.

Emma Dionne, who recently graduated from SMCC, took an INBRE-funded research course in December at MDIBL.

“I fell in love with the atmosphere, with the people, with everything having to do with it,” she says.

Working with a senior research scientist, the focus was on a fruit fly gene thought to have potential for understanding the effect of neural biology on behavior.

“It was phenomenal to be involved in a project that had to do with the brain,” Dionne says. “It gave me a good idea of, How do we start a project? How do we know where to begin? It was an incredibly eye-opening experience.”

Hailing from the Auburn-Lewiston area, Dionne, 21, earned a full ride at Brandeis University.

She credits INBRE, and the community it formed, as key to her journey.

“To hear their stories and how much they truly loved science was so inspiring,” she says. “To have them on LinkedIn and on emails has been so reassuring. And it’s something I would never have had without INBRE.”

The program gave that extra bump in her Brandeis application. “To have that competitive edge has been incredibly important for me,” Dionne says. “I’ve learned X, Y and Z and am prepared to dive in whole-heartedly.”

Effective thinking

INBRE shaped Sally Molloy’s career and her ability to train undergraduates in research.

Molloy, an associate professor at the University of Maine Honors College in Orono, has been a principle investigator on INBRE-funded research on how bacteriophages — viruses that infect bacteria — contribute to antibiotic resistance. That research leveraged further NIH funding.

INBRE also supports a year-long foundational course that gets students digging up soil samples, isolating and analyzing bacteriophages in the samples using sophisticated equipment and techniques and presenting their findings.

She refers to INBRE as a powerful way for students to learn, to build confidence and self-esteem, and to develop problem-solving skills and science literacy.

“It’s a great way to start students off on research learning in the first year,” says Molloy. “The goal is to help students not only learn basic research skills, but help them develop effective thinking strategies that will be important for doing good science. “

Research pipeline

“It’s had a big impact on my career and also on the experiences of a lot of students,” Timothy Breton, an associate professor of biology at the University of Maine at Farmington, says of INBRE.

Breton is using a National Science Foundation grant to support studies that continue his INBRE-funded research. Breton and his undergraduate assistants — hailing from INBRE members UMaine Farmington, Southern Maine Community College and Bates College — discovered a new gene in fish that might have an impact on understanding several human diseases. The students co-authored an article published in a professional journal.

INBRE also funded lab upgrades and equipment, such as a costly confocal microscope that provides superior imaging. Typically, “Institutions our size don’t get access to that type of advanced equipment,” Breton says.

Lab renovations and new equipment have leveraged further research grants. “Growing the ecosystem has mattered,” says Breton.

For a small institution like UMF, where students might not have even considered biomedical careers, INBRE helps stock the biomedical research pipeline.

“There’s really no substitute for working in a lab, with a professor supervising, in a small group, doing cutting-edge research,” says Breton. “You’re not just in a classroom reading a textbook. You’re going to make discoveries along with us.”

0 Comments