As sea levels rise, land trust puts marshes on spending list for capital campaign

Photo / Tim Greenway

Tim Glidden, director of Maine Coast Heritage Trust, left, and Jeremy Gabrielson, conservation planner, on the Cousins River on the Yarmouth-Freeport line, part of a parcel of preserve marsh the trust plans to buy and protect.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Tim Glidden, director of Maine Coast Heritage Trust, left, and Jeremy Gabrielson, conservation planner, on the Cousins River on the Yarmouth-Freeport line, part of a parcel of preserve marsh the trust plans to buy and protect.

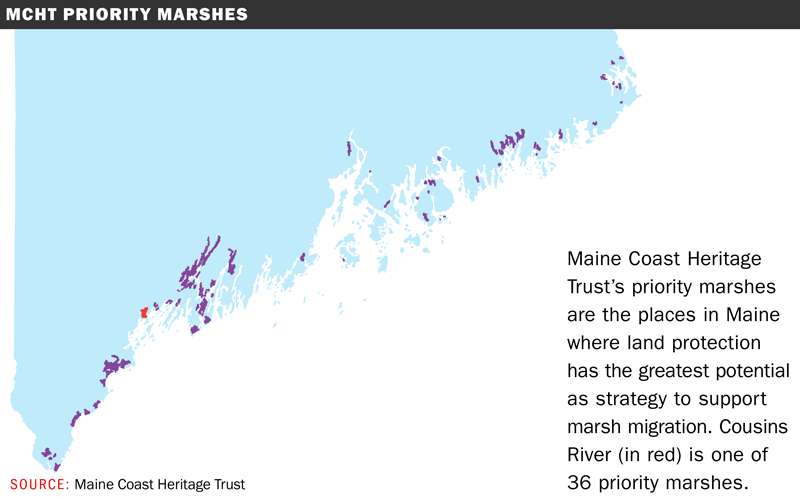

Just off Interstate 295 on the Yarmouth-Freeport line, barely visible behind the trees along the highway, the east branch of the Cousins River snakes through a vast expanse of marshland, surrounded by gently rolling upland covered in pines and deciduous trees.

Even with the highway noise, it’s a pastoral spot, free from the development that covers much of eastern Cumberland County.

The natural beauty is only a small part of what makes the land attractive to the Maine Coast Heritage Trust, which is in the process of buying 82 acres on the Yarmouth south side of the marsh, closest to Granite Street.

The property and surrounding upland, along with parcels like it up and down the coast, are one of Maine’s biggest tools to help the state’s coast adapt to climate change and the rising sea that will come with it.

The trust, which formed 50 years ago to help preserve land around Acadia National Park, has expanded both in reach and vision over the decades, and the Marsh for Tomorrow Initiative is now a major project.

“Every five years we do a strategic plan, and for the last few, climate change has grown in focus,” says Tim Glidden, MCHT executive director. “We’re trying to prepare for what things might look like 100 years from now.”

Last year, the land trust completed a $125 million capital campaign. Of that, $65 million was earmarked for land acquisition and creation of public access and environmental protection programs; $42 million for stewardship; and $18 million for connecting people to the land through education, policy advocacy and other types of programs.

Since 1970, Maine Coast Heritage Trust has helped conserve more than 150,000 acres in Maine, from the Isles of Shoals to Cobscook Bay, including more than 300 entire coastal islands.

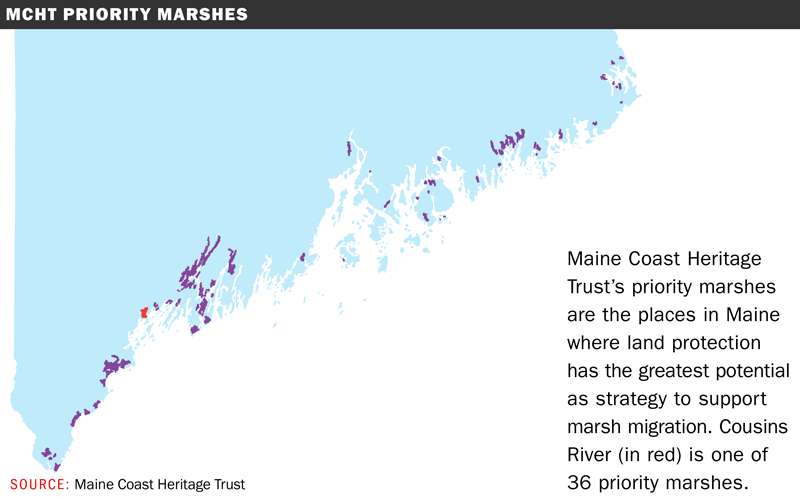

With the Marsh for Tomorrow Initiative, it aims to protect the undeveloped upland around the state’s salt marshes. The dry higher land, acquired through purchase or easement, will be clear from development to become marshland as the water rises.

Protecting the land is critical to sustaining the state’s coastal biodiversity, and the economy that goes with it, Glidden says.

The state’s coastal marshes are largely clustered along the southern Maine coast and Downeast. They save the state millions of dollars annually through erosion control, reduced flood damage and pollution abatement, the trust says.

A wide variety of the state’s commercial and sport fish species spend some portion of their life cycle in marshes — including clams, mussels, and lobsters — before they venture out to the ocean. The marshes are also duck and shorebird habitat, and feeding grounds for osprey, herons and eagles.

They also absorb carbon dioxide and provide a buffer for storm surges.

Largely unchanged since the glaciers receded, Maine’s marshes will disappear as the global sea level rises in the next 100 years. The rocky parts of the coast are immovable, so much of the higher sea level will flow into the tidal marshes. While the three to six feet the sea will rise may not seem like much, it will be enough to flood the state’s 22,000 acres of tidal marshland. By conserving the land around the marshes now, there will be room for new marshes to form.

An imminent threat

“Natural systems are incredibly resilient, and have been for thousands of years,” Glidden says. “When given the chance to regenerate themselves, they’re back at it, and the results are immediate.”

The trust, through partnerships with landowners, municipalities and other land trusts, has conserved more than 1,600 acres of marsh in Maine. It has identified 67 parcels in the state that, like the Cousins River marsh, meet the criteria of being relatively large, with a variety of plant species and having adjacent upland that hasn’t been developed.

While the sea level shifts that would flood the marshes may seem a long way off, acting now is vital, conservationists say.

“Look at how people responded to COVID-19,” says Jeremy Gabrielson, MCHT senior conservation and community planner. “It was immediate, because the threat was immediate. But climate change is even more of a threat. We’re looking at what we can do now.”

The state marsh areas ranked at the top for resilience by the MCHT are:

- York County’s marshes, the state’s largest;

- Merrymeeting Bay, where six rivers meet, and which spreads through Sagadahoc, Lincoln and Cumberland counties, considered one of the most important freshwater tidal ecosystems in the country, according to the Friends of Merrymeeting Bay;

- Pleasant Bay, in Washington County, which has nationally significant shorebird feeding areas.

‘Luck and strategizing’

The marsh along the east branch of the Cousins River is an ideal example of what the trust is looking to save, Gabrielson and Glidden say as they walk down an old tote road through a wooded grove to the marsh.

A farm for generations, spruces now pepper once-empty fields along Granite Street. Closer to the marsh, decades-old deciduous and pine trees cluster on a rolling landscape. It’s now owned by a conservation LLC, formed by the estate of the longtime owners.

The property is in protected status while the MCHT raises the $2 million it needs to buy the land.

The recently completed campaign allowed the trust to “make stunning progress”over the past six years to protect and oversee 35 new preserves and take care of them in the future, but it doesn’t cover much of the direct land acquisition, Glidden says.

“Going forward, we continue to raise the necessary funds to buy lands like the Cousins River marsh,” he says.

Much more of the land around the marsh, about 180 acres on 12 parcels, is protected by the Freeport Conservation Trust. The trust, which owns or has easements on 1,600 acres in town, is completing a $185,000 deal on 12.7 more acres of the marsh upland on Old County Road, across the town line from the Yarmouth parcel.

“We’ve just sort of slowly been collecting parcels,” says Katrina Van Dusen, executive director of the Freeport Conservation Trust.

The Royal River Conservation Trust is also a partner on the Cousins River Watershed Initiative. Once the two parcels have been acquired, most of the land surrounding the Cousins River west of I-295 will be protected.

The 12.7 Freeport acres are being paid for with grants from the National Wetland Conservation Act, the Davis Conservation Foundation, the Casco Bay Estuary Partnership, Kennebec Savings Bank and “a bargain sale from a conservation-minded neighbor.”

While development in Freeport and Yarmouth has eaten up a lot of farmland in recent decades, Van Dusen says the land in past years wouldn’t have been considered that desirable. In more recent decades, it’s been cut off by Interstate 295. The Maine Department of Transportation owns what remains of the land surrounding the marsh.

“It’s amazing now you can look at that whole undeveloped shore,” she says. “It’s just beautiful, with nothing on it.”

Preserving it has been “a combination of luck and strategizing,” she says.

Saving the pieces

Gabrielson says that while Maine doesn’t have the amount of marshland that some other states, like Maryland and New Jersey do, the state has done a better job of preserving what it does have.

“Maine still has most of the salt marsh it had after the glaciers receded,” he says. “As a result, the ecology has become really significant to the state.”

He says states that have lost huge amounts of land surrounding marshes to development are scrambling to preserve what they have left.

Preserving the land isn’t a hard sell for many landowners who are looking to sell an old family farm or other land, even if climate change isn’t top of mind, Glidden and Gabrielson say.

“Maine has a longstanding conservation ethic,” Gabrielson says. “A lot of [the marsh upland] is farmland, and Maine farmers have always felt a connection to the land.” He says the state is built on farming, fishing and working in the woods.

“Over the last 50 years, people are seeing that that way of life is at risk.”

Glidden quotes conservationist Aldo Leopold: “The first rule of intelligent tinkering is to save all the pieces.”

How things play out in the future will depend on a lot of factors, he says. “But if we don’t save the pieces now, it’s all irrelevant.”

0 Comments