Biddeford startup may provide farms with unusual field hands — robots

Courtesy / Farmhand Automation

Farmhand Automation — with Linzy Witherspoon in marketing and design, Nick Nelsonwood in mechanical engineering, Elliot Bradbury in software engineering and founder and CEO Alex Jones — is developing low-cost electric farming robots to help farmers transition to a carbon-free future.

Courtesy / Farmhand Automation

Farmhand Automation — with Linzy Witherspoon in marketing and design, Nick Nelsonwood in mechanical engineering, Elliot Bradbury in software engineering and founder and CEO Alex Jones — is developing low-cost electric farming robots to help farmers transition to a carbon-free future.

For small and mid-size farm owners, worker shortages are a continuing problem. But a Biddeford startup is working to create a labor pool of potentially easy hires.

Farmhand Automation is developing low-cost electric robots to handle the arduous task of weeding fields.

The autonomous platform is designed to help rural local farms scale operations to address growing food security pressures posed by climate change.

Founded by Kennebunk native Alexander Jones, the early-stage company has developed a prototype, is planning real-world trials and is targeting late 2022 for a commercial launch.

The company employs three staffers plus one contractor and is looking to hire three additional software development and mechanical engineering employees within the next six months. Click here to learn more about hiring opportunities.

Over the past two years, the company has invested $500,000 in Maine Technology Institute grants, loans and local angel investment. Farmhand Automation recently received an additional $250,000 through a Maine Technology Institute and Governor’s Energy Office joint initiative called the Maine Clean Energy Innovation Challenge, for product development, testing and field trials.

Mainebiz asked Jones about his startup journey and the connection between farming and robots. Here’s an edited transcript.

Mainebiz: What’s your background?

Alexander Jones: I went to Emerson College in Boston for its film program and worked in Manhattan for close to seven years, mostly as a camera engineer. In my late 20s, I dropped everything and moved to Portland to build a career here. That brought me to technology. It was 2014, 2015. There was a burgeoning web technology scene here and the start-up scene was really picking up. I wanted to start a small business.

My first entrepreneurial endeavor was in honeybee monitoring. I developed small-scale devices that go under the hive, connect to wifi and track the weight of the hive throughout the day. The weight goes down as bees leave to look for pollen. By the end of the day, you can tell how much honey has come in by how much the weight has increased.

It’s a niche market, mostly for hobbyist beekeepers, but at the time felt like a great way to make an impact in the agricultural world with technology. I was selling product mostly through beekeeping conferences, traveling along the East Coast. From there we started getting online orders. We sold about 150. That led me to Forager [a Portland developer of an app that connects local food producers and sellers] where I was the product manager.

But I wanted to explore robotics. So I went to the West Coast, worked in San Francisco briefly, then moved to Seattle to work with iUNU [a specialist in computer vision for agriculture]. We were building small robots, a little bigger than a football, that run on overhead tracks through a greenhouse and have a camera on the bottom, sort of like a drone without propellers. The robots take pictures of the plants below. We used computer vision and artificial intelligence to understand how well the plants were growing, whether there were diseases and helped growers keep track of inventory across several acres of indoor growing. iUNU was a great experience.

MB: Why did you start your own company?

AJ: I was always interested in farming and had done farm apprenticeships in upstate New York. At the same time, I became aware of how challenging farming is. I was excited by the opportunity to use technology to make it easier to start and scale small and mid-size farms.

MB: How did you land in Biddeford?

AJ: My partner Linzy and I heard Biddeford was up and coming and the rents were cheaper than Portland. We needed an industrial base to build robots, but close to lots of farms. We leased one acre from Broadturn Farm in Scarborough as our test field.

MB: What was your goal?

AJ: We wanted to figure out how to reduce the cost of starting or growing a farm. Sixty percent of a farm’s cost is labor. A lot of that labor is for basic repetitive tasks like weeding or turning over the soil. Those are jobs that are underserved. But much of the workflow can be automated with simple tools. That’s what we’re approaching with robotics.

MB: What have you built?

AJ: We started with a rover — like a Mars rover — that can drive over farm beds. That’s the big thing — there’s no off-the-shelf robot that can straddle a bed of vegetables. We had to figure out how to build it at a low cost, with low-cost tools, so we could sell it at an accessible price point for local farms. Our target is to reach a price of $25,000 per unit.

MB: How far along is development?

AJ: We’re on our fourth-generation prototype now and we’re doing longevity and resilience testing, along with tool development. The rover is 5 feet wide by 3 feet deep by 2.5 feet tall and weighs 150 pounds with tools. The first tool we’re developing is a weeder. The idea is to have it be able to do light weeding in the top two inches of the soil to disturb weed growth without destroying the soil structure and beneficial soil organisms that support plant growth. We want to follow that with a seeder and a transplanter. But we’re focused on weeding now because it’s one of the most expensive and labor-intensive tasks aside from harvesting.

MB: How is the robot powered?

AJ: The robot has internal batteries and we have a solar base station with another big battery that gets charged all day, so the robot can charge itself. The idea is that you can have the robot run all day and night.

MB: Can the robot find its way to the charging station by itself?

AJ: Yes. The farmer has to set waypoints to tell the rover where it can go, but it can move freely from there. The robot is equipped with high-precision GPS that we use for the navigation and tools. Another piece that we’re still developing is adding lightweight sonar sensors to the front and back of the robot so that it can avoid basic obstacles.

MB: How does the robot know what is a weed and what is a plant?

AJ: We’ve taken a different approach to most agricultural robots in that we’re not “looking” for the plants at all. Typically in small-scale farming, you mark your beds with where you want your team to plant seedlings or seeds. We’re taking over that process with the robot to mark the soil for the farmer, and we record the position where each plant should go with the GPS. Later, when we come back through with weeding tools, we weed everything between the known plant locations the same way a tractor would drive down a row of lettuces with a cultivator. It’s a different approach than scanning for plants and weeds with computer vision, but it’s essential to reducing costs and making this technology accessible to farmers.

MB: Where are you working on this?

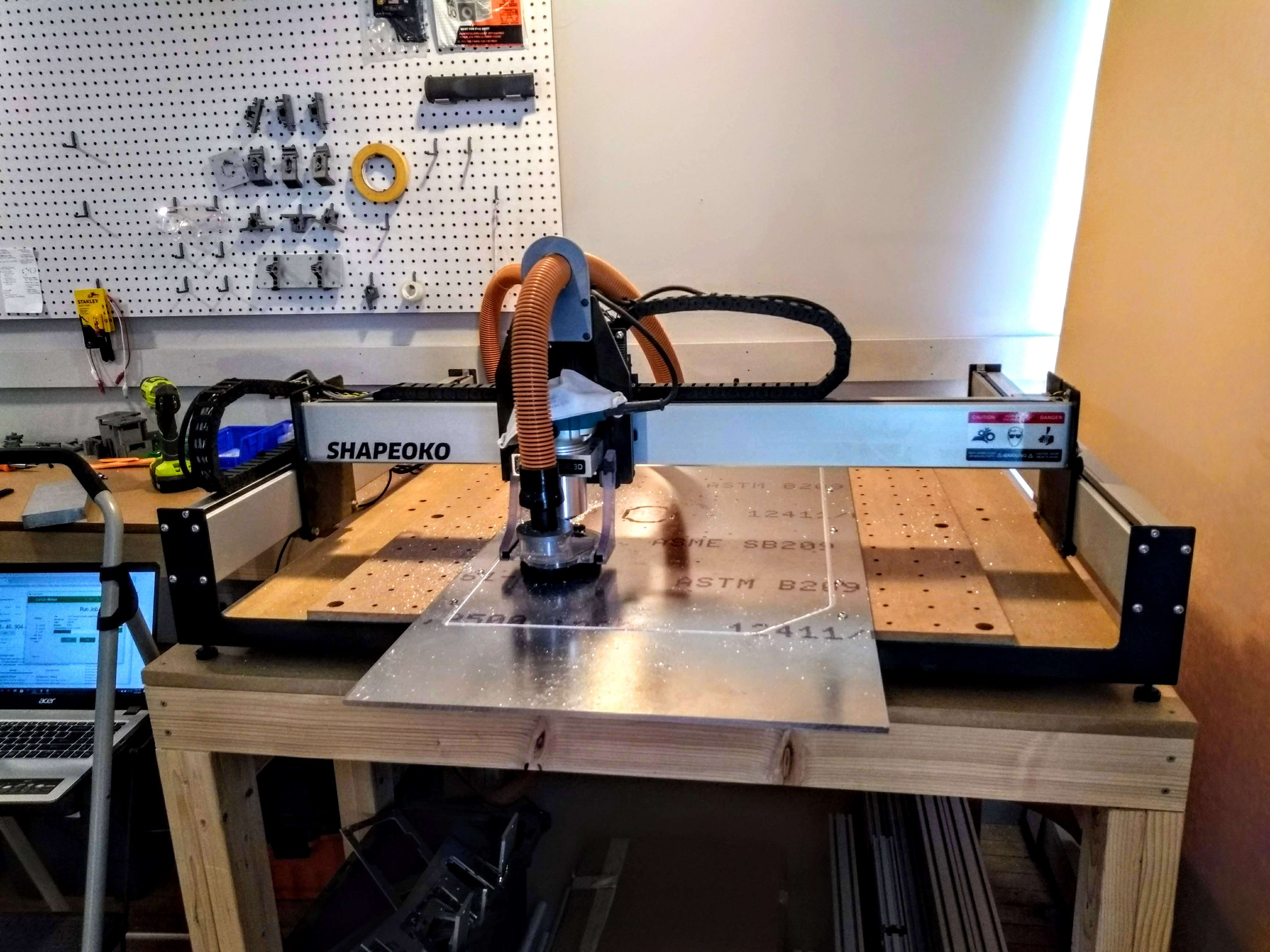

AJ: We signed a three-year lease last month on a 2,000-square-foot space at 432 Elm St. Before that, we were working in a 550-square-foot space at the Counting House [a historic building converted to artist studios at 24 Pearl St.] We use several low-cost CNC machines and 3D printers working together to make our machines.

MB: Tell us a bit about how the robot is made.

AJ: The system has a main computer sitting on one corner of the robot and various sensors spread throughout the system. You have the motors, the actuators, the wheels and the tools. These systems have to communicate with each other securely and we’ve been working with open source initiatives to develop robust communication channels over standard ethernet, like you would use on your router at home.

We build all our own software out of necessity, and we focus on designing systems in such a way that makes it accessible and not overly sophisticated. We do this, first, to make it easy for farmers to work with the technology and, a close second, to work with as much local tech talent as we can. We know not everyone is Maine is going to have robotics experience, so we use a lot of web-based technologies to bridge the gap with the skill sets here in Maine.

MB: What are next steps?

AJ: We’ve lined up farms as early-trial partners for next year. We hope next season to launch a YouTube channel to give people a real-time look at day-to-day use of the system and how it’s performing on our farm. We’re targeting to launch our first 25 commercial units by the end of 2022.

The biggest feedback we get from people in the technology world is how fast and how cheap we’re building the robots. But we’re not building rockets. It’s more realistic to build a robotics startup in this day and age because a lot of it has become a lot easier. The same way that Portland and other places saw an explosion of software startups, we believe we’ll start seeing more robot startups in the next five to 10 years. It’s a really exciting way for people to engage with their communities in the physical world and open new markets.

0 Comments