Maine's reliance on retail sector exposes vulnerability | A heavy reliance on sales tax and jobs means Maine's economy will take a hit from an ailing retail sector

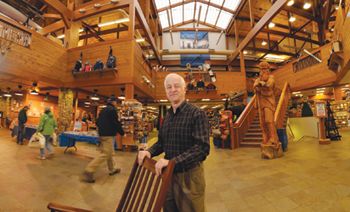

When the economy has sputtered, Kim Adams, whose family has sold sporting goods at the Kittery Trading Post for 80 years, said his business usually continues to run pretty smoothly. Adams, a vice president and co-owner of the Kittery store, said customers have traditionally detoured off the Maine Turnpike to buy outdoor accessories at his store regardless of the larger financial picture.

“In the past, we felt we were somewhat recession-proof,” he said.

This year, however, Adams said the effects of the economic downturn have been unmistakable, especially in the second half of the year as the financial crisis became more acute. With traffic on the Maine Turnpike down about five percent this year, Adams said there has been a corresponding decrease in the number of customers entering his store. And those who do come through the door are spending less. Adams said overall sales at the Kittery Trading Post, which did $50 million in sales last year, are down somewhere in the range of 10%.

As a result, managers at the Kittery Trading Post, like those at many other retailers in Maine, are cutting back sharply on holiday staffing and have been paring down inventory in order to avoid being stuck with unsold merchandise. Adams said he anticipates his family’s business may be in a defensive posture well beyond what is expected to be a very subdued holiday shopping season. “Sales are definitely not what they should be,” he said. “I don’t expect any significant uptick for the next 18 months.”

Months before economists decided to label the current economic downturn a recession, retailers noticed a precipitous drop in consumer spending. The sudden dearth of shoppers is wracking the entire economy, and retailers have been among the first and most severely affected. In Maine, the drop in sales means the seasonal jobs some residents rely on to make ends meet may not be available this year. The retail slide is also pinching state revenues and, according to at least one longtime watcher of the Maine economy, is likely to have an overall effect on the state’s economic health that is proportionally greater than the number of jobs lost.

Retail jobs hit hard

Mainers, and even more so people from other parts of the country, may think of the Pine Tree State as a place where people find work as niche manufacturers, lobstermen and lumberjacks. In fact, the top occupations in Maine are retail salespersons and cashiers, and three of the state’s five largest employers, L.L.Bean, Wal-Mart and Hannaford, are retail stores.

Retail sales have gained influence over the Maine economy in recent years partly because of growth in the retail industry and partly because of the steady attrition of manufacturing jobs. Though other sectors like government, education and health care are all significantly larger, retail sales currently account for approximately 14% of jobs in Maine. Retail employment peaked in Maine in November of last year at 88,800 jobs, according to state employment figures. In 2002, the retail sector accounted for 85,900 jobs.

The Maine economy’s growing dependence on retail jobs is in keeping with a shift in the national economy. The U.S. Economic Census shows the retail sector grew at an average annual rate of 4.7% between 2002 and 2007, while the Gross Domestic Product grew an average of three percent per year during the same period. And at least one University of Southern Maine economist predicts the consumer-led recession will impact Maine more acutely than most other states.

Susan Feiner, a professor of economics and women’s studies at USM, said poorer people tend to lose more income proportionally during times of rising unemployment. Since Maine, on average, is poorer than most of the nation, she said retail sales can be expected to plummet farther in Maine than elsewhere.

“The decline in retail sales in Maine will be larger than the average decline in the United States,” she said.

Shoppers are keeping a tight lock on their wallets all over the country, and consumers in Maine may be especially receptive to the new spirit of frugality. “We’re Mainers, we’re good at cutting back,” said Nancy Lawrence, owner of Portmanteau, a custom-made bag and clothing shop on Free Street in Portland.

Maine retailers, large and small, have been quick to respond to consumer curtailment by cutting back on one of their most flexible expenses: seasonal help. At the Kittery Trading Post, for instance, the store is only hiring half its typical holiday work force of 75 people this year, according to Adams. At L.L.Bean, which last year hired 7,000 seasonal workers at pay rates of between $11 and $15 per hour, the company has cut its seasonal hiring by 23% this year, according to company spokeswoman Carolyn Beem.

The recession is hitting retail employment more severely than other sectors. In the last year, Maine has lost 4,500 jobs, a third of which were in retail sales. “Retail accounts for about one-third of all job losses but only accounts for 14% of jobs,” said Glen Mills, director of economic research for the state Department of Labor.

Even year-round staff at Maine’s top retailers are not immune — on Dec. 2, Hannaford Bros. Co. offered employees at its Scarborough headquarters voluntary resignation in anticipation of layoffs the company plans to make in January.

Disproportionate impact

The erosion in retail employment is expected to continue. Muskie School of Public Service professor Charlie Colgan, who chairs the economic forecasting commission for the State Planning Office, predicts that retail, along with construction, will be one of the hardest hit sectors of the Maine economy. Colgan forecasts the state will lose 3,500 retail jobs by 2010, a drop of four percent from the sector’s peak in 2007.

Jobs in retail sales typically lack benefits, are often part-time work and usually register on the low end of the pay scale. The median wage for a cashier in Maine in 2007, for instance, was $8.39 an hour, according to the state Department of Labor. But Colgan believes the disappearance of these jobs has a disproportionately hefty effect on the economy.

Since part-time retail jobs are often the last resort for people who were laid off from other full-time work, their disappearance can often force people out of the work force and into the ranks of the unemployed, he said. Furthermore, retail jobs are often the first jobs people take when re-entering the job market. Colgan said the expected decline in these jobs is likely to make it harder to climb out of the recession.

“The income loss is not as large as a loss of 3,000 manufacturing jobs, but the effect on the economy is serious,” he said.

Feiner, who directs the women’s and gender studies program at USM, points out that a recession driven by a mass consumer retrenchment is also likely to have a severe effect on female workers. The retail sector has a high percentage of part-time workers and 70% of those who work part-time are women, Feiner said. The professor said these women are likely to be displaced both through the elimination of their jobs and when full-time workers, who are more likely to be male, are pushed into part-time positions.

The state’s finances are another casualty of the downturn in retail sales. The state sales tax generated $983.1 million in fiscal year 2008 and accounted for nearly a third of Maine’s $3.1 billion general fund revenues.

With sales tax revenue down 3.2% this September from the same period last year, state forecasters are quickly revising their predictions downward for this revenue stream in fiscal year 2009. The Maine Revenue Service forecasting commission recently reduced estimated collections from sales tax for the coming year by $20.8 million, according to state tax analyst Jerry Stanhope. “The fact that consumers are spending less is going to have an impact on state revenue,” Stanhope said.

Bad timing

The accelerated downturn in retail sales couldn’t come at a more unfortunate time for retailers, many of whom rely on the critical holiday shopping season for nearly a third of their income. But several retailers said they had been preparing for the slump since early this year. At L.L.Bean, where company executives anticipate 2008 sales will remain flat at last year’s level of $1.62 billion, this has meant reducing inventory and staffing since the spring, according to Beem. The company is also running a holiday promotion to stir up sales in which customers who spend $50 or more receive a $10 gift card.

“I think the general consensus is it’s not going to be a fast turnaround and we’ll continue to take a cautious and conservative approach to business,” Beem said.

Some smaller retailers said they are also keeping a close eye on costs but have managed not to cut any employees. Gail Diamon, owner of Dodge the Florist on Brentwood Street in Portland, said she enjoyed strong sales this summer and then saw orders fall off by close to 10% in October. She said she has cut back on giftware but reasonably solid demand for flowers has allowed her to keep her staff of five employees intact. Though many businesses have curtailed their purchases of flowers for holiday parties, Diamon said her sales have held up well.

Diamon said she believes people may substitute flowers for more expensive indulgences during tough economic times. “It’s not a necessity, but people still do go for flowers,” she said.

Lawrence, who has run her custom-made clothing shop in Portland for 30 years, said sales of her handbags and clothing quickly diminished after the turmoil in the financial markets broke out this fall. Still, she has retained both of her employees and Lawrence said consumers’ growing interest in shopping at locally owned businesses appears to be surviving the downturn.

The downtown shop owner said she still had to make adjustments and the small size of her business has allowed her to be nimble in responding to the downturn. Since she and her employees make all their products on-site, she said it has not been difficult to keep inventory in line with the pace of business.

“We make things as they sell,” she said. “I kind of can’t be left with too much inventory.”

Another challenge facing the retail sector in Maine and elsewhere is apparent not in the Old Port but out along the Maine Turnpike. Many observers believe there is more retail space in this country than consumers can support.

In recent decades, the growth of retail space across the United States, mainly in the form of big-box stores, has been tremendous. Retail space per capita has grown from four square feet in 1960 to 38 square feet in 2005, a rise of 850%, according to Portland author Stacy Mitchell, an advocate for local economies and author of the 2006 book “Big Box Swindle.” During the same period, median income in the United States, when adjusted for inflation, increased 80%.

Colgan, too, said he believes “the sector as a whole is almost certainly overbuilt,” but he said Maine is unlikely to see many large retail stores go dark. Most of the latest wave of retail development in Maine was built toward the end of the recent growth cycle, Colgan said, and these stores are still recapturing their investment costs, making them unlikely targets for closure.

Historically, when the economy does pull out of a recession the turnaround is often led by the same retail businesses that were among the first to lead the downward slide. This time, though, Colgan said that may not be the case.

“This recession, because the consumer has essentially deserted the field, we might not see that same pattern,” he said.

It’s not a pretty picture for retailers but many still find consolation in the long view. Diamon’s flower business, started in 1867, as well as L.L.Bean and the Kittery Trading Post, are all multi-generational business that survived the Great Depression and times of economic hardship that the current recession is unlikely to rival.

“We’ve seen lots of ups and downs in the last 96 years in business and I fully anticipate we’ll come out as strong as ever,” Beem said.

Seth Harkness, a writer in Portland, can be reached at editorial@mainebiz.biz.

Comments