With wages going up, Maine businesses hurdle higher to hire

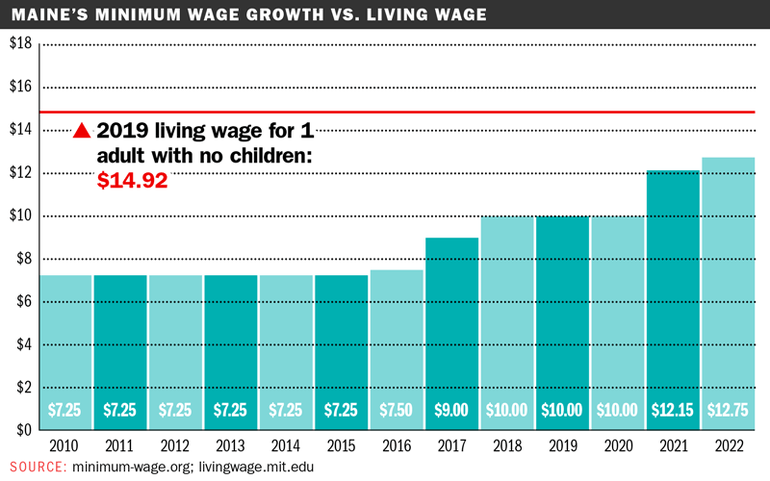

For now, Maine’s minimum wage is $12.15 an hour. For an employee working 40 hours a week, that translates to $486. For the year, that would be $25,272. Maine’s living wage in 2019 was $31,043 according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator. In 2022, the minimum wage will be $12.75.

For now, Maine’s minimum wage is $12.15 an hour. For an employee working 40 hours a week, that translates to $486. For the year, that would be $25,272. Maine’s living wage in 2019 was $31,043 according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator. In 2022, the minimum wage will be $12.75.

Minimum wages are going up, with $15 an hour becoming the norm. Businesses such as Maine Medical Center and Bangor Savings Bank have pushed their minimums even higher, to $17 and $18 an hour, respectively. Sign-on bonuses are common, with Portland paying $3,000 bonuses to attract school bus drivers.

And still, hiring is the toughest it has been in decades.

“Fifteen dollars an hour is the baseline. It’s more like $17 to $18 is the minimum if you’re not fast food,” says Said Eastman, CEO of JobsInTheUS, which operates JobsInME. “If you’re paying someone less than $32,000 a year to work full-time, the likelihood of you attracting candidates is slim. A minimum living wage is closer to the $20 range.”

Scott LeClair, Hannaford’ Supermarkets’ director of talent, says the hiring market is the most challenging he’s seen in his 40 years with the grocer.

“Competitors are pulling out all the stops, so we need to be on our game,” LeClair says.

Hannaford recently held a two-day hiring event across all of its stores with the goal of getting 1,000 new employees. It had immediate interviews available and talked to about 2,000 people. It ultimately hired 1,100 of them.

The “days of hiring” event was so successful that Hannaford now plans to do that seasonally to beef up stores with big summer client bases, and to build hiring for the fall and winter holidays, LeClair says.

Hannaford actually had to increase staffing during the pandemic as people ate at home more often rather than dining out. Hannaford now employs about 35,000 workers.

Hannaford average hourly wage is “well above” $15 an hour, LeClair says. He declined to cite Hannaford’s base starting salary.

Companies are paying more for each hire, through bonuses, benefits and hourly wages, recruiters say. And companies need to get used to these higher wage levels.

“Wage inflation is here to stay. One thing this pandemic has taught job seekers is that they are way more valuable than they had been led to believe. Companies are getting the message the hard way,” Eastman says.

For example, Eastman worked with a company that needed customer service workers, as well as shipping and receiving workers willing to do the “second shift” or night hours. The customer service job, which offered remote work from home options, got more views online and 100% more applicants than the shipping and receiving gig.

“It’s much harder to show up at a facility at a certain time, work a physical shift at odd hours. If you need to fill that role, the premium isn’t $1.75 an hour. It’s got to be much, much more,” Eastman says.

Currently, it takes the average company about 45 to 90 days to find the right employee, Eastman says.

‘Keep recruiting’

Bob Montgomery-Rice, Bangor Savings Bank’s president and CEO, says recruiting needs to be constant.

“You have to be very active in recruiting on a constant basis. Even when you have all your jobs filled, you keep recruiting,” Montgomery-Rice says.

It’s not just about the money. Other factors such as flexible work hours, a family-first environment, proximity to home, tuition reimbursement and benefits are what workers are shopping for, recruiting executives say.

For small businesses, it’s difficult to compete on benefits, and matching higher wages can be challenging. The best way for a small business to recruit is to become enmeshed with the community and find people through word-of-mouth and referrals from local contacts, recruiters say.

“You have to be looking all the time, well before you actually need someone,” says Holly Lancaster, director of recruiting for KMA Human Resources Consulting LLC.

One-time bonuses have been successful for some employers, but that just reshuffles the labor force from one company to another. It doesn’t really improve the overall job market participation.

Maine’s labor market participation, which reflects those people who are employed or unemployed and actively looking for work, remained about 60% in October or 2 percentage points less than before the pandemic.

The statewide unemployment rate for October was 4.9%, roughly about the same level it has been for nine months.

“The trends started before the pandemic for both clinical and non-clinical roles. The pandemic exacerbated the hiring challenge and we’ve had to double-down on our efforts,” says Thomas Ter Horst, Maine Medical Center’s vice president of human resources.

For Maine Medical Center, the five most challenging areas to fill are registered nurses, certified nursing assistants, surgical technicians, imaging technicians and environmental service workers, Ter Horst says.

“It’s fair to say we’re seeing less applications. But we’re still doing a lot of hiring,” says Ter Horst, who added that Maine Medical Center hired 2,200 people in the past year. The hospital employs about 7,000 people.

“We need to get used to the labor shortage. It existed before COVID, continued through COVID and will be how we operate going forward,” Ter Horst says.

Power shift

“The power in hiring has shifted from employers to employees,” says KMA’s Lancaster.

“Candidates now say ‘tell me why I should work here,’” Lancaster says. “It’s unlike any market I’ve ever seen. It’s harder to find all levels of people.”

Ten years ago, Lancaster says companies expected to see an average of six years per company on a resume. Now, the norm is two to three years. People are job-hopping more often and shopping for benefits that fit their lives, she says.

Remote work isn’t a draw for every person. Some people are extroverts or young people looking to be around their peers.

“What people want is flexibility. Flexibility in hours or days of the week, and flexibility in their work/life balance,” Lancaster says.

Hannaford’s LeClair agrees.

“How do you overcome the issues that are affecting women in the workforce? Flexibility. Parents should be there for their families, and have flexible work schedules to allow that to happen,” LeClair says.

Hannaford says one draw has been its tuition reimbursement and reduced tuition partnership with Husson University and Southern New Hampshire University, as well as partnerships with the community colleges.

“We have five generations in the workforce. We need to meet the different needs of those different groups,” LeClair says.

During the pandemic, the people who lost jobs in fields like tourism, hospitality or cleaners have moved on and gotten new jobs. Now, there’s no filling those jobs with foreign workers due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and local candidates aren’t interested in going back, recruiters say.

The real estate boom showed that Maine can attract people — but those people came with jobs in hand and are often working remotely, Eastman says.

“People always talk about, ‘How can we keep talent in Maine or attract young people to the state?’ Better wages and better work environments are a start,” Eastman says.

Retention is key

“Once we get new associates in the door, how do we retain them? How are we training them and advancing their careers,” LeClair says. “If we don’t retain people, it’s not worth it. There’s a cost to training new people and there’s a loss to the company when institutional knowledge is gone.”

“It’s one thing to start people at a certain level, but you need to keep people and retain people,” LeClair says. “We want to help people find the right paths and know this company can be a career, not just a job.”

When Maine Medical Center announced in July its $61 million effort to raise wages across its system, hike its minimum wage to $17 an hour from $14 an hour, and offer referral bonuses, sign-on bonuses, and other efforts, it noticed a difference in hiring, Ter Horst says.

Increasing wages helped attract workers, especially making it easier to hire environmental services workers, he says.

“It helped us at Maine Med be more competitive,” Ter Horst says.

Still, Maine Medical Center’s overall turnover rate of employees is about 14.6%, which is an increase over the average rate of about 10%, Ter Horst says.

To retain workers, Maine Medical Center has made an investment in training, such as its programs for CNAs and scrub techs.

For the two-year scrub tech program, Maine Med pays candidates to go to training and they emerge with skills, and a career path. Meanwhile its seven-week CNA class also pays people to be trained. Teachers and management get to know the students and they can be immediately hired into a unit.

“We want people to have advancement opportunities. We want people thinking about career pathways and we can help make that happen,” says Jennifer McCarthy, Maine Medical Center’s chief operating officer.

0 Comments