Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Capital pains | A drying up of venture funds leaves Maine short on startup cash

Photo/Leslie Bowman

Robert Phelps of Bar Harbor BioTechnology

Photo/Leslie Bowman

Robert Phelps of Bar Harbor BioTechnology

Photo/David A. Rodgers

Michael Gurau, a venture capitalist in Maine, worries the state's fledgling entrepreneur community could wither without more investment

Photo/David A. Rodgers

Michael Gurau, a venture capitalist in Maine, worries the state's fledgling entrepreneur community could wither without more investment

Robert Phelps made a decision as the new head of Bar Harbor BioTechnology in 2007 that even he describes as worthy of his employees’ ire. The company had conceptualized a new genetic research tool that allowed scientists to better determine molecular changes in cells, and Phelps wanted it on the global market as soon as possible. The implications for disease research and treatment were big, and time was of the essence. “I was a jerk,” he recalls now. “I actually put a countdown clock on our website.” It worked — the product moved from concept to commercialization in four months, becoming available for sale in October 2007. “It was like Cortez burning the ships,” he says, referencing the Spanish conquistador’s historic decision to destroy his vessels upon landing in Mexico to eliminate even the most fleeting thought of retreat.

Founded in 2006 as the first commercial spinoff of The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor BioTechnology managed to break even by the end of 2009, and Phelps is now aiming for revenues of at least $35 million with hopes to grow its staff of seven to 50 within five years. His is the kind of innovative, high-growth startup that the state seeks to attract, and the kind that couldn’t have survived without the help of a small but critical slice of the business funding pie: “BHB wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for venture capitalists,” Phelps says. VCs are the adrenaline junkies in our capital markets, the investors who jump in early with offers of funding in exchange for equity and the high of big profits down the road. Phelps’ countdown clock was just the kind of no-holds-barred commitment to the bottom line that they chase.

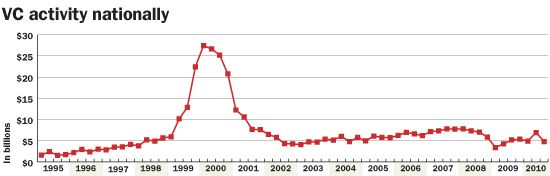

But venture capital funds have shriveled nationally as a result of the recession, and Maine is not immune to the trend. Not only have wealthy individuals and institutional investors, like pension funds and university endowments, pulled back their contributions to venture capital in light of plummeting performances on their “safer” investments like stocks, but venture capital investors have also had a tough time realizing returns through the sales, mergers or IPOs of their portfolio companies.

So, completing the vicious cycle, VCs are less able to provide returns back to their institutional and individual investors, further exacerbating already tight liquidity. Meanwhile, the demand for startup capital has only increased. “A lot of people got burned by early-stage development that took way longer than anyone thought to grow and become profitable, then, perhaps more importantly, reach liquidity,” says Nat Henshaw, managing director of CEI Ventures Inc., a community development and finance institution.

The market for early-stage capital under $1 million was far from vigorous before the downtown and now is as bad as it’s been since the VC industry formed, according to Michael Gurau, president of CEI’s other venture fund, CEI Community Ventures, and a Mainebiz columnist. Nationally, venture capital investing plummeted 47% in the first half of 2010 compared to the same period last year, accounting firm Ernst & Young LLP reported in October. The value of companies financed by venture capital fell more than 18% at the end of the second quarter from the end of 2009, according to the Dow Jones U.S. Venture Capital Index.

By some measures, venture capital plays a limited role in the state’s economy. It’s estimated that barely 1% of Maine companies are backed by such funding and few venture capital funds are based here. But it underpins the growth of ambitious companies that eventually realize dramatic profits, providing startup capital when banks and other lenders balk at the risk. Companies including Wright Express in South Portland and Westbrook’s Idexx depended on venture capital in their early days. “Lack of early-stage funds is an epidemic that will result in something of a lost generation of opportunity that will be missed for lack of seed and early capital,” Gurau says.

The players

The taxpayer-supported Small Enterprise Growth Fund, a revolving fund created by the Legislature in 1995, is perhaps the most dynamic venture capital outlet in Maine right now, with 15 active companies in its $13 million portfolio and an influx of $4 million from the jobs bond approved by voters in June. But other firms have either shifted to later-stage development, such as Portland’s North Atlantic Capital, or are fully invested, meaning they’re working only with their existing companies and don’t have cash for new investments. “It’s a pretty thin landscape out there,” says SEGF Fund Manager John Burns. Plus, companies with high growth potential are few and far between, returns haven’t been strong and fewer new funds are being created, he says. “Fewer funds and fewer dollars being invested means fewer deals for Maine,” he says.

SEGF, which typically invests $100,000 to $300,000 in Maine-based companies, “can’t carry the needs of the market on its small shoulders,” Gurau points out. The “capital gap” — or the disparity between supply of and demand for capital — has long been a feature of the venture capital market, but has widened during the recession, he says. “There’s a flight from risk, and risk is highest in the earliest stages.” CEI Community Ventures, the $10 million fund Gurau heads up, is among those without available capital.

Masthead Venture Partners, a $125 million fund headquartered in Boston but with an office in Portland, is in a similar boat. “Most of our peers here are in the same situation,” says principal Timothy Agnew. “They’re fully invested.” It’s taken longer over the last couple of years to sell portfolio companies or launch IPOs, what VCs term “liquidity events,” and therefore longer to pay back investors and raise new funds, he says. “If you don’t have to sell something, in most cases you don’t, because prices aren’t good.”

The market does appear to be rebounding, with activity lackluster in the third quarter but on pace to top the poor showings of the last two years. IPOs have picked up, with 40 venture-backed companies going public during the first three quarters, compared to 18 in 2008 and 2009 combined, according to the National Venture Capital Association. Still, that figure is dwarfed by the heydays of 2000, when 264 venture-backed companies went public. “On a national basis, I wouldn’t say it’s back to normal, but investing is happening at a pretty healthy pace,” says Agnew.

In New England, Massachusetts takes the cake for the most venture capital activity, far outpacing Maine with nearly $3 billion invested last year, second only to California. That fact led Massachusetts to make the biggest jump of any state on the Forbes Best States for Business Ranking this year, from No. 34 to No. 16, even though business costs there are the highest in the country. As many in Maine’s business community would like to forget, the Pine Tree State came in dead last on the list.

Even though the average Maine business doesn’t rely on venture capital, the funding plays a critical role in the state’s economy, says Henshaw of CEI Ventures, which is currently raising more capital. “If it’s working well, it creates good employers here in Maine that are growing and healthy.”

Without venture capital, Maine’s burgeoning innovation economy will wither, according to Gurau. “Whatever entrepreneurial community is forming here or has formed over the last few years will dissipate,” he says. The potential for Maine to attract further investment in research and development and to commercialize big ideas is at stake, he says. “I worry that it’s not going to be realized if we can’t get companies formed as a result and have the companies stay in Maine.”

Investing in Maine

Nyle Systems, a heat pump manufacturer in Brewer, just won its first round of institutional venture capital funding from the Small Enterprise Growth Fund. Initially supported by four angel investors — affluent individuals who complement traditional VC funding — Nyle is looking to expand the potential applications of its technology in lumber drying, residential water heating and energy recovery systems. “What it will allow us to do is basically accelerate our growth,” founder and CEO Ton Mathissen says of SEGF’s investment. “The angels can only bring it so far.” The company and its 20 employees are preparing to expand into space left vacant by auto parts maker ZF Lemforder and will break even this year, he says. “In five years, we hope to grow tenfold, in revenues, employees, et cetera.”

While venture capital has turbo boosted Nyle’s growth, at Bar Harbor BioTechnology, a cohort of Nyle’s in SEGF’s portfolio, its role has been even more striking. “We would be a crater hole without this kind of funding,” president Phelps says matter-of-factly. Venture capital represents about 70% of the company’s money, totaling somewhere between $2 million and $5 million, he says, avoiding specifics. The company has relied on a mix of private and public funding, with its first and only round of venture financing led by New Hampshire-based Borealis Ventures, which was joined by the SEGF and the Maine Technology Institute.

Bar Harbor BioTechnology has just launched a new division to introduce a genetic test that, with the swab of a baby’s cheek, can predict not only the child’s risk for developing certain diseases, but also when during its lifetime the illness is likely to strike and with what severity. Armed with such information, doctors will be able to determine the best drugs to treat such patients and the dosages, as well as which drugs to avoid, Phelps says. “We’ll be able to do this with a whole plethora of diseases,” including colorectal cancer, Alzheimer’s, rheumatoid arthritis and irritable bowel syndrome.

Such promising technologies can win venture capital funding these days, but investors won’t cut corners with their due diligence, Phelps says. “You definitely have to be the cream of the crop. You have to bring something that really catches attention.” Adopting a ruthless loyalty to the bottom line doesn’t hurt either. “I came into it with a complete capitalist, complete profit-driven mindset,” Phelps says, unlike the scientists who work for him. “And that is venture capital-friendly.”

Jackie Farwell, Mainebiz senior writer, can be reached at jfarwell@mainebiz.biz.

The state’s role in VC

Maine legislators have made a couple of notable efforts in recent months to stimulate capital markets. One bill passed while the other died due to the tight budget outlook.

In April, Gov. John Baldacci signed into law LD1, “An Act To Stimulate Capital Investment for Innovative Businesses in Maine,” which authorized the Maine Public Employees Retirement System to invest up to $20 million of its pension funds into venture capital and called for the creation of a new Innovation Finance Program

“An Act to Improve the Seed Capital Investment Tax Credit Program,” sponsored by then-Sen. Libby Mitchell, would have boosted a state program that’s designed to encourage investment in Maine’s young business ventures, both directly and through private venture capital funds. LD 1666 sought to expand the credit from 40% to 60% and make it refundable, but died in appropriations after unanimous approval by the taxation committee. It could be reconsidered in the current session.

Venture capital funds in Maine

Maine Angels

Funds available: Yes

Fund size: N/A

SEGF

Funds available: Yes

Fund size: $13M

Masthead Venture Partners

Funds available: No

Fund size: $160M

CEI Ventures Inc.

Funds available: No

Fund size: $20M

CEI Community Ventures

Funds available: No

Fund size: $10M

North Atlantic Capital

Funds available: Yes

Fund size: $75M

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments