Getting schooled | Applying the methods of UMaine's star innovator to the system's quest for greater relevance in the work force

The energy ratchets up the moment innovator extraordinaire Doug Hall takes the stage at the University of Maine conference center. Stepping to the microphone before a crowd of 200 attendees in the earth-toned banquet room, Hall begins a presentation that’s something of a cross between a late-night infomercial, a religious revival and a university economics class.

Organizers of the day’s event — a University of Maine System summit held in Orono earlier this month geared toward helping the system better align its programs with future work force needs — chose wisely in placing Hall early in the lineup. An inventor and former idea man for Procter & Gamble and other Fortune 500 companies, Hall is the stout and balding embodiment of a fresh approach. He recently founded a new minor at the Orono campus called Innovation Engineering that many would like to see implemented systemwide. And he started the daylong event off with a bang.

Hall eschews the typical trappings of public speaking, including the podium, note cards and even footwear. A barefoot Hall clicks a PowerPoint slide into view and launches into a speedy and often breathless summary of his approach to creativity and commercialization, a methodology based on “meaningful uniqueness,” or the quality of a good, service or cause that makes customers willing to pay more for it.

Hall, a 1981 graduate of UMaine’s chemical engineering program, has brought the concept to corporations including American Express and Nike through his consulting company, Eureka! Ranch. Put more bluntly, “If you’re not unique, you better be cheap,” he says. The strategy behind the maxim is based on three steps: creating, communicating and commercializing your unique idea.

Hall burns through topics ranging from barbecue smokers to Star Trek in explaining his message, as though he’s trying to cram a full semester of Innovation Engineering coursework into a single hour. Many in the University of Maine System have heard his appeals before, often referring to his energetic speeches as the “Doug Hall experience.”

The university has invested much in Hall, and vice versa. Describing his goal to see Maine continue as an innovation leader, Hall proclaims with no small amount of intensity, “I will fight to the death for the righteousness of our cause.”

But is the University of Maine System adhering to Innovation Engineering principles itself as it pursues greater relevance in Maine’s evolving economy? The April event was designed to encourage feedback on how the system can better prepare its students to work in Maine. If a well-equipped work force is the system’s meaningfully unique “product,” how does it plan to create, communicate and commercialize its way to success?

Creating

One of Hall’s tenets is to never just blindly do whatever your customer wants. In other words, the customer is not always right. But the University of Maine System’s April event was designed to find out just that — what its customers and stakeholders seek.

The key, according to Chancellor Richard Pattenaude, is that the seven-campus system needs to collect the input in the first place before deciding what to do with it. “You reduce risk by starting with information and data,” he says. Reflecting on the summit two days after its conclusion, Pattenaude says he thinks UMS has so far earned a passing grade from Hall.

The summit was far from the system’s first attempt to gather information. The event grew out of “New Challenges, New Directions,” a restructuring plan for the 45,000-student system that was the culmination of a six-month assessment process. The plan, among other directives, calls for more than $12 million in highly contested cuts that would lead to the elimination of 80 faculty positions by 2014, some undergraduate majors and some master’s degree programs.

Foreign languages, music and art are among the program areas targeted for cuts. The summit on work force needs fell just days after the announcement of the cuts, and professors from those disciplines took advantage of the opportunity to discuss the role liberal arts should play in the education of Maine’s public university students. Andrew George of Eastern Maine Development Corp. in Bangor, one of few private enterprise attendees at the event, addressed the friction in the room during an afternoon feedback session. “I wouldn’t announce cuts before a summit,” he told the crowd. “The tension here, it’s,” he paused, “interesting.”

Tony Brinkley, a longtime UMaine English professor and former Maine Center for Economic Policy board member, challenged a presentation on work force demographics by John Dorrer of the Maine Department of Labor. Brinkley questioned why liberal arts competencies weren’t well represented in Dorrer’s data, which focused on the skills sought by employers.

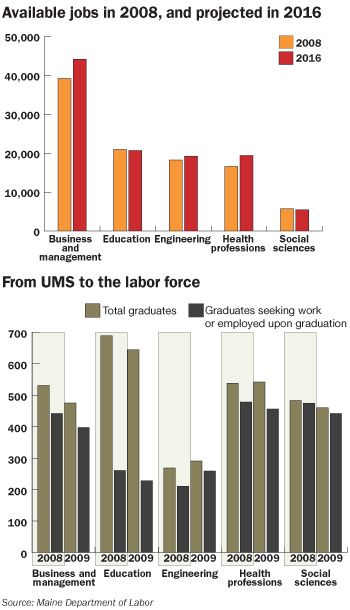

Dorrer highlighted jobs in business, management, education, engineering and health professions, saying Maine must plan ahead to ensure its graduates are prepared to fill future vacancies. “You don’t put in a call to Hollywood and say I need five more dentists, give me five more RNs,” he says. What matters isn’t whether a student is a French or a music graduate, it’s how that student fares in the labor market, he explains.

Suggestions from attendees about better preparing Maine’s graduates included developing interdisciplinary majors, beefing up international language and culture programs and creating a focus on gerontology, given the state’s aging population.

But the overarching theme to emerge over the course of the day was better collaboration — between the system and the community colleges, among professors at the seven campuses and even among academic departments on the same campuses. Not a single person from the community college system was spotted at the event and members of the business community were few and far between.

Communicating

The shortage of private industry types at the event can be attributed more to logistics than to a lack of engagement, according to Chip Morrison, president of the Androscoggin County Chamber of Commerce. Morrison, a kinetic personality with boundless energy rivaling that of Doug Hall’s, made the trip from central Maine to attend the daylong event. Others weren’t so willing. “The center of the business community is not Orono,” he says. “If you want to engage the business community you can’t give them a two-hour and 15 minute drive or more.” Or ask them to stay for the whole day.

Still, Morrison says, he loved the program and credits the UMaine System for “getting all the parts pulling in the same direction.” Given the tough economy, “They need to be more nimble,” he says. “That’s true for all organizations.”

Key to increasing the system’s flexibility will be integrating its vision with those of the state’s other educational avenues, from K-12 to adult education to Job Corps, says Steve Pound, another attendee and associate director of the Cianbro Institute, the Pittsfield construction company’s recruitment, work-force training and development entity. Pound, a former school superintendent and teacher at Acadia University in Nova Scotia, says finding a way to give potential students credit for skills learned outside a traditional UMaine System classroom must be part of the plan moving forward. “If we say [higher education] is accessible for all, we need to find ways to make it accessible for all, and not just financially, but recognizing prior learning.”

Chancellor Pattenaude “would have liked to see a few more” faces from private industry at the summit, but he says the system is reaching out to the business community in other ways, including meetings with the sustainable energy industry and planned conversations with the Legislature’s Business, Research, and Economic Development Committee. Each campus also has a board of visitors made up of local business leaders, alums and others. As for getting friendlier with its community college counterparts — who were invited to the summit — the system has signed about 150 articulation agreements to better align programs. “[The summit] was not the sole place where we have this conversation,” Pattenaude says.

The system has also established groups to assess needs in seven disciplines: nursing; STEM, or science, technology, engineering and math; tourism and hospitality; world languages; innovation and graduate professional programs. James Breece, vice chancellor of academic affairs, describes the groups as a way to follow Wayne Gretsky’s famous advice to “go where the puck is going to be,” not where it already is.

UMS Trustee Tamera Grieshaber’s comments at the summit offer some perspective. Employers still seek three basic skills: communication, organization and critical thinking, she says. “They haven’t changed, folks,” she tells the audience. “They’re the same skills they’re looking for now.”

Commercializing

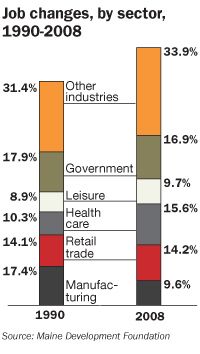

Laurie Lachance, president and CEO of the Maine Development Foundation, furrows her brow in concern as she clicks a PowerPoint slide into view. Tasked with updating the summit’s attendees on the state of Maine’s economy, she displays a multicolored bar chart showing it costs the average Mainer 36% of his or her income to attend a public four-year college. That’s compared to 28% nationally.

Minutes before, Lachance had informed the audience that the state ranks about 30th in the nation in per capita income. Not exactly encouraging data. At the same time, she says, education remains the single most important determinant of Mainers’ earning potential, health and numerous other factors. “The road to college starts at birth,” she says.

In-state tuition at the University of Maine in Orono for the 2009-10 academic year totals $17,974 including housing and fees. The board of trustees last May approved a 5.8% increase for full-time undergraduate students, a marked improvement from the 10.3% jump during the 2008-09 year, but still a challenge for many families. Add a mortgage, car payment and day care costs, and returning to school or attending college for the first time as an adult becomes even more daunting.

“Commercializing” the UMaine education will no doubt be part of the system’s work to establish a public agenda, work that will continue in earnest over the summer. Those efforts must include anticipating students’ and employers’ future needs, even at the risk of making the system’s current offerings obsolete, according to the Doug Hall approach.

As Hall begins to wind down his whirlwind presentation, he clicks to a slide illustrating the three adjustment periods that education, business and government leaders can expect to experience in applying his innovation principles. First is confusion (a photo of a man screaming with his hands clasped to his head in frustration). Second, connecting the dots (a little boy wearing sunglasses appearing to experience a eureka moment.) And last, confidence (a person silhouetted against an open landscape, arms raised high in triumph.)

Hall concludes his speech, and his audience rises from their seats in a standing ovation. He takes a deep bow, seeming to use the moment as much to catch his breath as to acknowledge the applause.

Jackie Farwell, Mainebiz senior writer, can be reached at jfarwell@mainebiz.biz.

Comments