Is ‘agri-energy’ an answer for Maine’s dairy industry?

Photo / Fred Field

Jenni Tilton-Flood at Flood Brothers Farm, Maine's largest dairy farm, which is partnering with Summit Utilities Inc. to produce biogas.

Photo / Fred Field

Jenni Tilton-Flood at Flood Brothers Farm, Maine's largest dairy farm, which is partnering with Summit Utilities Inc. to produce biogas.

At Flood Brothers Farm in Clinton, Jenni Tilton-Flood calls it “black gold.” Dairy farms produce a lot of manure — and they’re looking for new ways to make use of it.

With 1,800 milking cows, Flood Brothers is Maine’s largest dairy farm. It also has 4,600 acres to grow food for the cows eat. Each mature cow produces 100 pounds of manure per day, most of which is now used to build in nutrients in the crop fields.

“It’s not a waste,” says Tilton-Flood, whose husband Dana, is a co-owner of the farm, which includes 21 family members across three generations. “It’s a vital part of how we grow our soil, raise our crops and continue the circle of life.”

But the circle of life could go beyond that. As a producer of methane, black gold can also be a fuel source. That’s why Summit Utilities Inc., a privately held natural gas provider based in Littleton, Colo., has partnered with Flood Brothers and other central Maine dairy farms on ways to produce biogas, which can be converted to electricity or a heat source for cooking and other tasks.

Energy partnership

Summit plans to build an anaerobic digestion facility on the Flood Brothers farm and create renewable biogas from manure provided by Flood Brothers Farm, Caverly Farms, Misty Meadows Farm, Wright Place Farm, Taylor Dairy Farm, Veazland Farm, Simpson View Farm and Gold-Top Farm.

In exchange, the farms will receive byproducts of the digestion process — nutrient-dense liquid effluent that can be used as a soil amendment, and a dry mixture that can be used for cow bedding or for compost.

“We’ll be lending them the manure,” says Tilton-Flood. “They’ll get good stuff out of it. For us, it’s like getting paid with time. Instead of moving and storing manure, we’ll have more time available to manage our farm. That’s big.”

Anaerobic digestion is common elsewhere in the world. But the concept is relatively recent in Maine, where there’s only one facility so far. In Penobscot County, Exeter Agri-Energy works with Stonyvale Farm and Agri-Cycle to produce biogas. Food waste supplied by Agri-Cycle is used in the fuel mix. The facility, which is in the town of Exeter, went live in 2011 and today processes 30,000 gallons of manure per day.

A critical mass of manure is needed to make the venture possible, says Dan Bell, Exeter Agri-Energy’s president. The relationship with Stonyvale, Maine’s second-largest dairy farm, makes the investment worthwhile. And Stonyvale receives back fertilizer, soil additives and animal bedding.

Summit found that critical mass in the Kennebec County town of Clinton, where five farms contribute 17% of Maine’s overall dairy production.

The dairy partnership is new for Summit, says CEO Kurt Adams.

“Clinton is a dairy cluster and there’s a lot of infrastructure,” he says.

Summit expects the digester will be operational by early 2021. The digester, which uses anaerobic bacteria to break down manure, will be on the Flood Brothers farm. A pipe will run from there to Summit’s existing natural gas system, near the farm.

Tilton-Flood views the project as a win, with valuable byproducts for the farms and a role in addressing climate change.

“This project is something we farmers would love to do but can’t, because there’s not enough time and it’s a lot of money,” she says. “Exeter Agri-Energy broke ground with research and development, not to mention permitting and convincing people this works. The more that people do this, the more normal it will seem.”

Challenges and opportunities

The project is an opportunity in an industry that faces numerous challenges, from pricing beyond farmers’ control, to rising costs and weather vagaries.

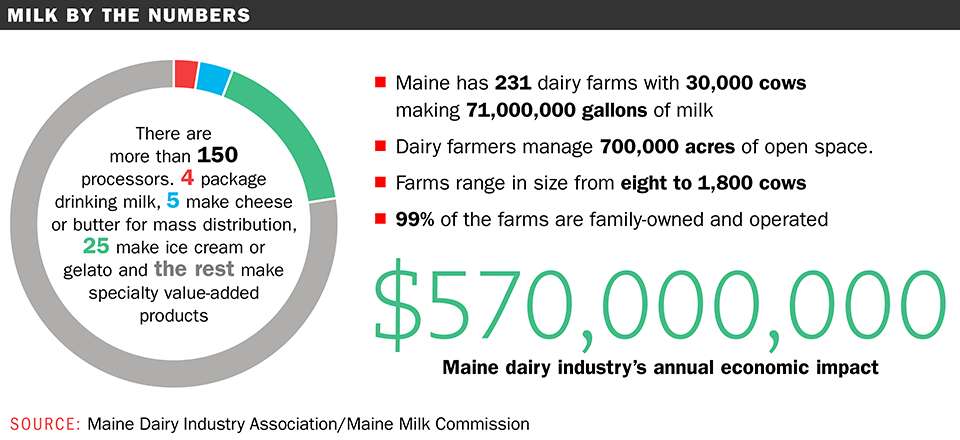

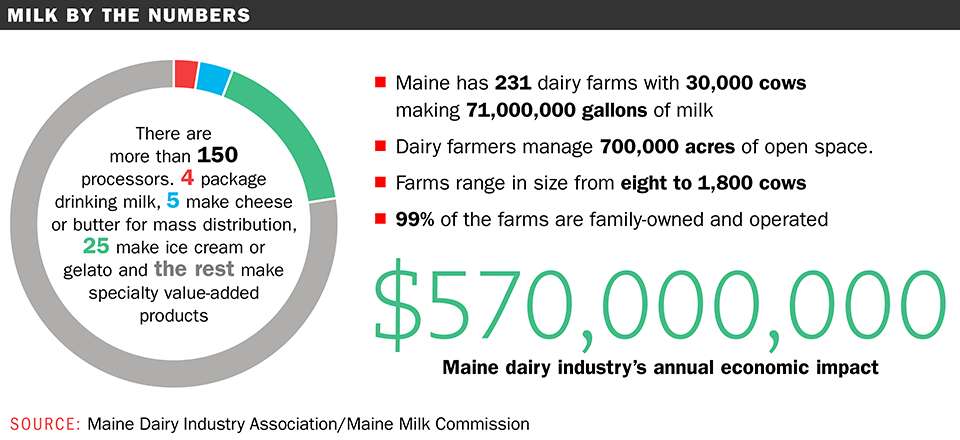

Maine’s dairy farm industry is comprised of 231 dairy farms. Most are family-owned and, generally, break-even operations. Rising production costs, coupled with volatile milk prices, make it challenging to balance the books.

Farmers have improved efficiency, but there’s an ongoing need to find new income streams from value-added products.

“There are several challenges we face as dairy farmers,” says Ben Taylor, co-owner of Taylor Dairy Farm in St. Alban’s. “During cropping, our schedules are completely dictated by the weather. Because we work with animals, and they never take a day off, there is always work to be done with them every day of the year. We also can receive emergency calls anytime around the clock.”

In addition, Taylor says, farmers have no control of the price of the product they sell “and, unlike some other industries, we don’t have the ability to close our doors during times of low prices because the cows need to be milked and fed every day.”

Julie-Marie Bickford, executive director of the Maine Dairy Industry Association, cites rising costs for things like utilities, equipment, transportation and feed, plus labor shortages, as primary challenges. Labor costs are also rising.

“You need to pay more to find the person to show up and milk the cows at 2 a.m.,” says Bickford. “Plus, farming today is highly technical,” with farmers grappling with food-safety, technology, animal husbandry and strict regulations getting milk from udder to jug.

With labor demands that go beyond what entry-level workers can offer, more farms now offer health insurance, on-site housing and higher salaries.

Dairy farmers, Bickford says, embrace the lifestyle but also have to be a little bit of everything — experts in animal husbandry, crops, bookkeeping, human resources, mechanics, government rules and regulations. Bickford credits farmers for their creativity in maintaining sustainable operations, using strategies like diversification into value-added products such as yogurt.

Pineland Farms Dairy Co. in Bangor is an example of diversification. Maine’s largest cheesemaker, it sources milk from Maine farms to make over 1 million pounds of cheese a year. It’s looking at expanding its facility, cheese production and geographic market, and diversify into a milk-based ingredient for wholesale producers of mashed potatoes, soups, and more, says Mark Whitney, the company’s president.

Pineland is looking to create products that Maine isn’t already making, diversifying the offerings.

“We want to come up with products that aren’t made in Maine and not available from other processors,” says Whitney.

Dairy cluster

Location and cooperation have helped Clinton remain a strong dairy cluster, says Tilton-Flood.

When Tilton-Flood arrived in Clinton, in 1993, she recalls almost 15 dairy farms there. Now there are five. But Clinton remains a dairy hub, partly due to proximity to transportation and processors, making it possible to ship milk on a timely basis. Clinton’s dairy farms are member-owners of Andover, Mass.-based Agri-Mark, a cooperative of 1,200 farms throughout New England and New York and owner of the Cabot and McCadem brands.

“Being a farmer-owner of a co-op means you’re not alone,” Tilton-Flood says. “You have a network and a voice.”

Dairy farms are part of a value chain that includes other sectors like grain producers and equipment dealers, trucking, farm support services and animal health.

“These are things people don’t think about,” says Tilton-Flood. “People see what happens when a mill shuts down and 400 people aren’t punching a clock. We know it hurts the sandwich shop and the retail store. But people don’t think about when a dairy farm, tucked up in the back woods, is no longer shipping milk. People don’t understand the domino effect that causes.”

0 Comments