Prisons' economic value debated

The town of Milo has for two years tried to convince the nation’s largest private prison company to build a correctional facility at its industrial park. Corrections Corporation of America was sufficiently interested in 2008 that it sent an engineering firm to inspect the site, but momentum waned following a lack of enthusiasm for the project at the state level. But Governor-elect Paul LePage earlier this month visited Milo to follow up on his campaign pledge to meet with town and CCA officials to try to make the deal happen.

The opening of a privately run prison in the Piscataquis County town would mark Maine’s first foray into the incarceration of its inmates for profit, a practice currently prohibited by state law. Making that leap with Tennessee-based CCA would bind Maine to a company with not only vast experience with such public-private partnerships and record revenues last year, but also a history of lawsuits and allegations of poor treatment of its inmates. Meanwhile, the company’s interest in Milo is tentative at best. Even if policy at the state level changes to allow for-profit prisons in Maine, CCA hasn’t committed to building here.

The hoped-for prison in Milo, a town of fewer than 3,000 in the county currently saddled with Maine’s highest unemployment rate of more than 12%, could create up to 300 jobs. But even if CCA commits to the project, research into the economic impacts of private corrections facilities in rural areas “suggests that prisons may not generate the nature and scale of benefits municipalities anticipate or may even slow growth in some localities,” according to an April report by the Congressional Research Service.

“We’ve got nothing else in the hopper here,” says Milo Town Manager Jim Gahagan. “It really could make a difference in our area.”

The corrections industry

Nationwide, state and federal officials are becoming increasingly reliant on a small group of private companies to build and operate prisons. Shrinking budgets coupled with an unprecedented boom in inmate populations — due to strict drug enforcement, stringent sentencing laws and high recidivism rates — have made cost-efficiencies a top priority, according to the Congressional Research Service report, “Economic Impacts of Prison Growth.”

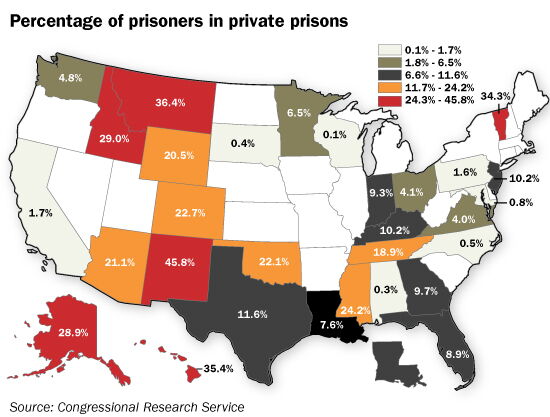

At the end of 2008, 2.3 million adults were in state, local or federal custody, a 400% jump from several decades prior. Private prisons housed 8% of those inmates in 2008, after the industry rebounded from a decline in the late 1990s due to overbuilding and failed reorganization efforts, the report states. Nearly all prisons opened in the United States between 2000 and 2005 were private.

Federal contracts have spurred much of the industry’s rebound, and accounted for 40% of revenues at CCA in 2008, according to the report. The company had record revenues of $1.7 billion in 2009, driven by continued growth in inmate populations and better compensation rates. The company owns 44 facilities throughout the country and manages another 21, for a total of nearly 87,000 beds in 19 states.

In Milo, talks have centered on a prison that would house approximately 2,000 inmates and employ 200 to 300 people. Maine’s prison population currently stands at roughly the same level, about 2,100, up 20% from 2002 to 2010, but the system employs 1,350, many more than are proposed for CCA’s facility.

The department’s budget for the 2010-11 biennium is $294 million. The Legislature has twice rejected legislation that would have allowed the state to house prisoners at for-profit facilities out of state, in the 2008-09 and 2010-11 budget years. CCA at the time told state officials it doesn’t consider expanding to areas where there’s no possibility of its facilities housing state prisoners, according to David Farmer, deputy chief of staff for Gov. John Baldacci.

Should that change under LePage’s administration, CCA would “explore” building in Maine. Durign Maine’s gubernatorial race, CCA donated $25,000 to the Republican Governors Association’s Maine PAC, which spent significantly on LePage. “We meet on a regular basis with policymakers around the country to assess what their corrections needs are,” company spokesman Steve Owen says. “Policymakers in Maine have not made a decision on what their needs may be.”

Many states have turned to private prisons in search of cost-savings, but whether the facilities work as an economic development tool is the source of much debate. Some studies show modest gains for towns home to such prisons, while others suggest they can hamper economic development by creating a stigma that discourages other types of investment, according to the Congressional Research Service report. Private prisons also tend to pay their workers far less than government-run facilities. The median annual salary for employees at private prison companies was $28,900 in 2008, compared to $38,850 for state workers and $50,830 for federal employees, the report found.

Treatment of prisoners at private prisons has also proven a hot topic, including for CCA. The company earned a reputation in the 1990s for poorly run facilities, while a corporate restructuring nearly forced it into bankruptcy and resulted in a $120 million settlement of shareholder lawsuits, according to a 2003 report by Grassroots Leadership, an advocacy group that works to abolish for-profit prisons.

Earlier this year, the state of Kentucky removed 400 female inmates from a CCA facility and placed them in a state-run prison in response to allegations of misconduct by CCA guards. Just this month, 18 inmates at a CCA jail in Hawaii sued the company saying they were stripped, handcuffed and beaten, while a recently settled ACLU lawsuit against the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement Agency over a CCA-run jail in California alleged poor medical care at the facility. Spokesman Owen says the company meets or exceeds national standards for its prisons. “I don’t think that three federal agencies, nearly half the states and the dozens of communities we operate in would do business with CCA if they didn’t have confidence that we were committed to safe, humane operations,” he says.

After talking with municipal officials in other towns where CCA does business, Milo’s Gahagan says he’s learned that the company is a good corporate citizen. “If they have 2,400 inmates in there,” he says of a CCA facility in his town, “that’s the population of Milo. It would be a town within a town. There’s going to be incidents from time to time.”

Comments