With new Portland home, Maine’s only medical school tackles doctor shortage

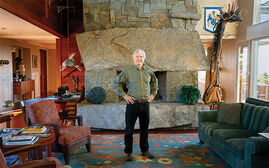

Photo / Tim Greenway

Dr. Jane Carreiro, University of New England dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine and VP for Health Affairs, in the new Harold and Bibby Alfond Center for Health Sciences on the Portland campus.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Dr. Jane Carreiro, University of New England dean of the College of Osteopathic Medicine and VP for Health Affairs, in the new Harold and Bibby Alfond Center for Health Sciences on the Portland campus.

When Ines Castro-Rosillo finishes medical school in 2028, she is aiming for a career in women’s health, while classmate Jim Barry is drawn to family medicine and the treatment of kidney diseases.

“My goal would be to open my own private practice somewhere in Maine near the coast, and one of my focuses would be to spend more time on patient education,” Barry says as he wraps up his summer of birding two-thirds of the way to his 100-species target.

Both are about to start their second year at the new Portland home of the University of New England’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, which offers two years of classroom instruction followed by two years of clinical clerkships. With a larger footprint in Maine’s largest city, the Biddeford-based university will graduate 200 doctors every year — boosting the annual class size by 35 to take better aim at the growing physician shortage.

By 2030, the U.S. faces a shortfall of 120,000 doctors, while Maine — where close to 40% of doctors are already within “retirement range” — will need 120 more primary care providers, according to estimates compiled by the Texas-based Cicero Institute.

While enrolling more medical students is the main motivation for UNE’s expansion, the next task will be to address the shortage of clinical training opportunities for students and residencies, which UNE President James Herbert says is critical to keeping more doctors in the state.

At the front end of the workforce pipeline, Maine’s only medical school will operate out of its new $93 million Portland home built to meet the highest standards in medical education but without trying to replicate larger, more established schools.

“We are not trying to be a ‘mini’-anything, including Harvard Medical School,” Herbert says. “The No. 1 priority of our medical school is producing first-class clinicians who will address the need for doctors in the state and region.”

The same goes for biomedical research, where UNE scientists are conducting important research but realistically “do not aspire to be a research powerhouse along the lines of Harvard or Hopkins,” he says.

‘Bibby’ era begins

This summer, 735 medical students will start the school year at UNE’s new building in Portland.

About the size of a Manhattan city block, the 110,000-square foot Harold and Bibby Alfond Center for Health Sciences — dubbed the “Bibby” in UNE parlance — puts the medical school on the same campus as the university’s other health professions programs from nursing to pharmacy.

That will help the medical school “close the loop” on interprofessional training and team-based care to improve patient outcomes, says Dr. Regen Gallagher, chief medical and compliance officer at Cary Medical Center in Caribou and an UNE alum who leads the university’s board of trustees.

As an employer of several fellow Nor'easters including six currently on staff, Gallagher says that UNE’s bigger class sizes will be “particularly helpful for our rural communities” but underscores the need for more residencies.

In the new building, medical students will be learning under one roof rather than having to commute between two campuses 20 miles apart and should see more of one another in and out of the classroom.

“Those interactions will be important is establishing real friendships and relationships,” says Dr. Jane Carreiro, a UNE medical school alumna who became dean in 2016 after more than two decades at the school in teaching and other roles.

When the newcomers arrive, their experience will be a far cry from Biddeford’s Stella Maris Hall in a revamped farmhouse where Carreiro studied in the 1980s and remembers sitting on “horribly uncomfortable hard blue chairs.”

Founded by the New England Osteopathic Foundation, it opened in 1978 with a dozen faculty members teaching 36 students.

Today, the older building houses several research labs. It will have more space for research and classroom learning following the medical school’s move.

With more than 4,000 alumni working in Maine and elsewhere, UNE’s medical school is among 41 in the U.S. accredited by the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation, which represents 197,000 students and physicians nationwide.

Growing field

Osteopathic medicine is a growing branch of medicine grounded in a holistic approach that looks beyond physical symptoms to consider the impact of lifestyle and socioeconomic factors on health and well-being. It also focuses on the interconnection between mind, body and spirit.

“We like to really consider the person and not the disease,” says Castro-Rosillo, who worked in public and community health research for a decade before medical school.

Classmate Barry got his introduction to osteopathic medicine in childhood, when he woke up one day with severe neck pain and stiffness that a DO relieved in two treatments.

“It was so effective, so quickly that it was almost hard to believe,” he says. “That’s when I knew I wanted to go to an osteopathic medical school and learn those medical skills.”

The discipline traces its roots to Dr. Andrew Taylor Still, a Civil War surgeon who believed that most ailments could be cured without conventional drug treatments. In 1892, he helped found A.T. Still University in rural Missouri as the country’s first osteopathic medical school.

Today, while 200,000 doctors of osteopathy make up only 11% of physicians nationwide and 28% of medical students are working in all medical specialties.

The profession is also getting younger, with nearly 70% of practicing doctors under age 45. It is attracting more women, who make up 45% of DOs in active practice and close to half of medical students. Conventional medicine is also increasingly incorporating biochemistry and other osteopathic principles to blur the distinction between the two approaches.

“Who knows if in 20 years from now there will even be two degrees?” Herbert says.

At UNE’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, “we teach our students through a philosophical lens that says that health is really the summation of what’s happening in the body,” Carreiro says. That includes specialized training on using “compassionate touch,” to gently stretch, apply pressure and manipulate joints and muscles to ease pain. That’s done in Osteopathic Manipulative Medicine Clinics, including a student-directed, physician-supervised community facility in Portland with twice the capacity it had in Biddeford.

Other features

Designed to reflect best practices in medical education, the Bibby includes flexible classrooms, team-based learning spaces, patient simulation labs and a top-floor anatomy lab for dissections. Rooms are wired for real-time simulcasting to other parts of the building, including giant screens in a 240-seat lecture hall.

That’s just one example of the advanced technology that will “allow communication interaction between every single room in the building,” Carreiro notes.

The building was designed by Portland-based SMRT Architects & Engineers, whose education portfolio also includes a residence hall and student center at the University of Southern Maine in Portland, and the Factory of the Future under construction at the University of Maine in Orono.

UNE’s new medical school building includes 20 rooms – double the previous amount in Biddeford -- for practice exams with people who are paid to play the role of patients. Four of the rooms, which simulate real family practices, can be transformed into in-patient hospital rooms.

“This is a game changer,” says Sarah Starbird, a retired physician assistant who recently started as a standardized patient at UNE and lives within walking distance of its Portland campus. “The technology is phenomenal.”

While standardized patients had to “kind of sneak around the back door” in Biddeford, the new building is much more professional, Starbird says. “You’re in the throes of this medical energy.”

Another big change made possible by the move is the placement of labs for slicing and cutting up cadavers on an airy top floor rather than a windowless basement. In the new location, there are windows to provide natural light for the space and rooftop ventilation for better air flow. The building was also designed to ensure greater privacy – and respect – for medical donors, SMRT’s Nick Vaughn says: “It’s not a situation where gurneys are being pushed through,” he explains. “It’s something the university is very sensitive to.”

Medical matchmaking

After freshly minted doctors graduate from UNE, more than half go into primary care fields and four out of 10 establish their practices in rural areas. In 2025, 97% of 165 graduates were matched to residencies, exceeding both the 93.5% national average for both medical doctors and 92.6% for DOs.

“Our students compete head-to-head with other students from every medical school in the country for residency slots,” Herbert says. “The good news is we do extraordinarily well.”

Among recently matched graduates, Bethany Miles will spend the next four years in MaineHealth’s psychiatry residency program, starting with two years at Maine Medical Center in Portland and then two years in the midcoast region. She looks forward to the experience though admits to being “kind of jealous” she won’t get to experience UNE’s new building. Noting that medical school is a “big, scary undertaking” with lots of ups and downs, she urges new and aspiring students to always “hold onto your reason why, especially during the downs.”

To keep more medical grads in Maine, UNE is working with hospitals across the state as well as the Legislature to create more training opportunities for students and more residency slots.

“Maine does not have a shortage of medical students,” Hebert says. “It has a shortage of clinical training opportunities and residencies.”

The gap exists statewide, with 13 of Maine’s 16 counties designated as health professional shortage areas with 3,500 or more patients for every provider. Low-income residents are also disproportionately affected by the lack of doctors.

As Dawson Turcotte gets ready to start his second year of medical school at UNE following a summer research internship in New Hampshire, he has a rural practice in sight.

“I grew up in Skowhegan, so I can imagine myself ending up either there or at least in the central Maine area,” he says. “It’s home, and I owe my state something. I want to give back.”

0 Comments