Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

York County planners target entrepreneurs

PHOTo / Tim Greenway

Master brewer Tod Mott left breweries in Boston and Portsmouth to start his own operation in Kittery, attracted by the town's up-and-coming vibe.

PHOTo / Tim Greenway

Master brewer Tod Mott left breweries in Boston and Portsmouth to start his own operation in Kittery, attracted by the town's up-and-coming vibe.

If economic planners in York County created an ideal case study of how regional development should occur, it probably would look a lot like Tod Mott's career path. In 2003, Mott and his family were living in Boston when he was hired as master brewer for the Portsmouth Brewery. Mott's daughter was attending a Boston high school, so he attempted to commute, but the trip wore him down.

"The commute north was not a problem for me. It was the drive south," Mott says. "I never knew how long it was going to take."

In a couple of years, Mott and his family moved north to South Berwick and he continued to work in Portsmouth, where he built a rock star reputation in brewing circles. Then, last summer he announced his resignation at the Portsmouth Brewery to focus on opening his own brewery in Kittery. He now is talking with South Berwick winemaker Andrew Bevan of Salmon Falls Winery to create a joint wine and beer venture. Kittery voters will decide in mid June whether to allow zoning changes approved by the planning board that would pave the way for the brewery/winery. While Mott believes the foodie scenes in Portland and Portsmouth are booming, he says he saw great potential in Kittery.

"Kittery is kind of a really cool place right now," he says. "I think there's a really great community."

Mott's story is music to the ears of planners in southern Maine who want to benefit more from the growth happening in Portland, Portsmouth and Boston. Their goal is to draw populations from the three cities and create more good-paying jobs for local residents, says Paul Schumacher, executive director of the Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission.

"York County is sort of a labor force exporter, I'd say," Schumacher says. "One of our goals is to try and retain those people within the region with new job opportunities and economic development."

Minding the gap

The economy of York County is intertwined with its big-city neighbors, so much so that economic data often treats Kittery as part of the Portsmouth economy. Portsmouth and Kittery blend, says Bevan of Salmon Falls Winery.

"Kittery is kind of like a Portsmouth community," says Bevan. "Anyone who lives in Kittery uses Portsmouth as its downtown."

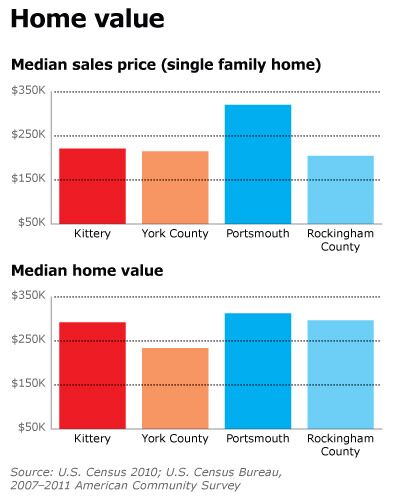

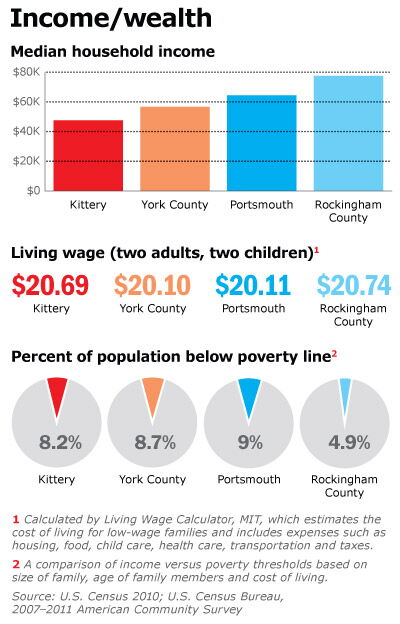

But economic data shows there is a big difference in income depending on what side of the Piscataqua River you live. According to 2011 U.S. Census data, Kittery residents have a median household income of $47,898, while the median income for Portsmouth households is $64,459. Income disparities between municipalities are not uncommon (census data shows that Trenton residents earn on average about $10,000 less than residents in Mount Desert, for example), but the economic gulf grows when county-wide data is considered. Households in Rockingham County in New Hampshire earn just over $77,000 annually, while York County households earn roughly $20,000 less. The percentage of residents in Rockingham County (4.9%) who live below the poverty line also is significantly lower than in York County (8.7%).

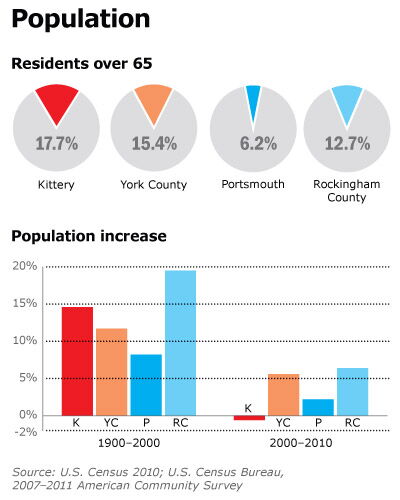

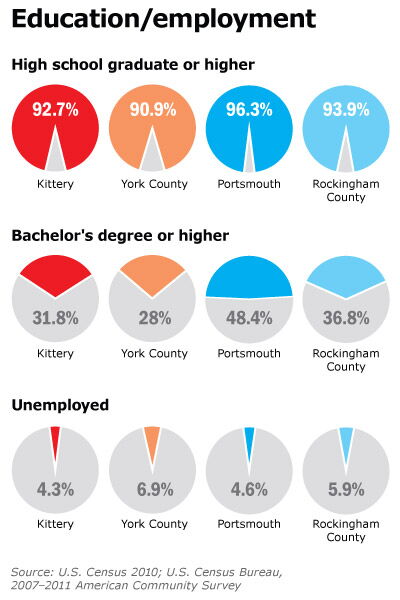

Some of that disparity can be attributed to age demographics, says Dr. Rachel Bouvier, an associate economics professor at the University of Southern Maine. York County has a higher percentage of residents over 65 (15.4%) than Rockingham County (12.7%). Another factor could be the nature of the jobs available, she suggested in an email. Rockingham County has more workers involved in management, while York County has more workers involved in the service industry.

"The earnings difference between the two occupations is probably a big contributor," Bouvier speculated in the email.

Creating a pull

New Hampshire has been receiving a lot of press attention for its success in attracting new residents from out of state, with some news stories going so far as to dub New Hampshire as "Boston North." A new report from the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire found that the state gained 80,700 residents from 2000 to 2010, and census data shows the state has consistently outpaced other New England states in gaining out-of-state residents.

But the migratory boom that New Hampshire has been riding might be slowing down, says Kenneth Johnson, a University of New Hampshire demographer. The recession slowed the influx of out-of-state residents down to a trickle, and New Hampshire's demography is beginning to gray, he says.

"The big question is what's going to happen as the recession wanes," Johnson says.

Portsmouth and Kittery might be booming, but their respective counties have seen the slowest population growth in decades. Between 2000 and 2010, York County has seen its population rise just 5.6%. It's a growth rate that other Maine counties would envy, but it's also the slowest the county has grown since the textile mills closed between 1950 and 1960. Rockingham County performed slightly better, growing 6.4%, but that still marks the county's worst growth rate since the Great Depression. The culprit has been the recession, says Johnson.

In the past, it's been difficult to get everyone in York County on the same page about how to grow as a region, says Mark Ouellette, executive director of Mobilize Maine, a statewide initiative that seeks broad collaboration to boost the state's economy. York County often operates as two separate spheres: the populous coastline and the rural interior. But the recession has helped planners and business stakeholders throughout the region come together to collaborate in ways previously not done, Ouellette says.

"When you have the sense of urgency from what has been a serious recession, that's when people are more open to working together," Ouellette says.

When examining demographics in Maine, the first instinct usually is to fret over the loss of young people. That's been especially true recently, since census data revealed that more people died in Maine between 2011 and 2012 than were born in the state.

But census data also shows that York County actually lost slightly fewer 20-to-24 year olds than Rockingham County between 2000 and 2010, according to an online census data comparison program created by Johnson and several other demographers. The data shows York County lost just over 23 individuals aged 20 to 24 per 100 residents, while Rockingham County lost nearly 30 individuals of that age range. It's normal for a region like York County to lose people this age as they leave for college or move to the bright lights of the big city, says Johnson. The trick is how to lure them back to settle down in their thirties, and Rockingham County edges York County in this all-important demographic. Rockingham County gained almost 31 individuals between the ages of 30 and 34 per 100 residents, which outpaced York's rate of 24 individuals per 100.

"They're the ones that man the volunteer fire departments and coach the soccer team," Johnson says.

York County is vying with Portland, Portsmouth and Boston for the coveted millennial generation, a group of young adults who value community more than previous generations as well as driving less. To succeed in capturing this demographic, regional planners are focusing on revitalizing downtowns, strengthening public transportation options and rethinking the nature of manufacturing in New England.

Redeveloping downtowns

The fruits of that strategy will be on display this summer in downtown Sanford, a former mill town that has some 30 brownfield sites, according to EPA estimates. Much of the sprawling mill infrastructure found on the banks of the Mousam River has lain vacant since the mid-'50s. Since that time, several generations of Sanford residents have listened to plans to revitalize the mill district, but they've seen few results, says Josh Benthien, a developer with Northland Enterprises LLC. That's left them skeptical, he says.

"All they've known is deterioration," Benthien says. "There is some understandable disbelief that things will change."

But if all goes according to plan, Northland Enterprises will complete renovation on some 66,000 square feet of mill space by the end of the summer, creating more than 20,000 square feet of retail space and 36 apartments. Using $3.5 million in federal and state grants and loans, Northland Enterprises partnered with the city of Sanford to clean up the site and renovate the mill. Already, the apartment complex has a waiting list of 200 potential tenants, more than half of whom live outside of Sanford. Some hail from as far away as northern Massachusetts, he says. Recently, the project gained its first tenant, a day spa. As news spread that the spa had signed on, interest has spiked among other area businesses, Benthien says. This rewards the city's vision, he says, as Sanford officials were adamant that they wanted a commercial component to the mill redevelopment project.

"They really wanted a first-floor commercial use," Benthien says. "They wanted something that would draw people to the mill district on foot and by car."

Grant and loan money also has been awarded to redevelop downtown mill sites in Biddeford and Saco. Overall, the Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission has won $1.4 million in grant money and $4.15 million in revolving loan funding from the EPA for brownfield development, and the city of Sanford has won another $1 million in grants.

Meanwhile, the town of Wells is trying to find strategies to create something like a downtown near its interstate exit, says Town Manager Jon Carter. The town is exploring ways to create commercial projects and affordable housing, while also taking steps to curb the proliferation of seasonal housing. Carter wants more affordable housing so the people who work inWells can stay in Wells.

"Firefighters, police, teachers, right now we have to import those people into the community," Carter says.

Smoothing the way

Wayne Davis, chairman of Trainriders/Northeast, had to fight long and hard to get train service to extend into York County. He had to fight even harder to get planners to think about making that train-line accessible to commuters.

But in the end, the Downeaster schedule was built to provide the possibility of commuting from southern Maine to Boston and back. Commuters have responded — about one-third of ticket sales for the Downeaster are multiple-ticket buys. Commuting passengers have helped push ridership on the Downeaster up to 527,000 passengers in 2011 and 2012, and not all tickets lead to Boston, Davis says.

"The ridership between intermediate stations is astounding," he says.

Anecdotally, it appears there's an increasing number of York County residents taking advantage of enhanced mass transit options to work. That option has gotten easier as telecommuting has gone mainstream; many professionals now only need to commute a couple of times a week to the big city, says Davis.

"We're seeing a lot of people moving into the community full time that work in Boston," Carter says.

Most of those commuters are still traveling by car. The most recent census data shows just over 90% of working residents in York County travel by car, with only 10% even carpooling to work. That's a lot of cars on the road, which makes the health of the turnpike a vital component of the economy of southern Maine, says Maria Fuentes, executive director of the Maine Better Transportation Association. Even minor improvements to the turnpike, like the recent opening of a no-stop E-ZPass lane at the Gray-New Gloucester toll plaza, is a big deal, she says.

"The turnpike is the most critical artery," Fuentes says.

Other transportation improvements have come from necessity. In June, 2011, the Memorial Bridge, one of three that connects Kittery to Portsmouth, closed for good. A new Memorial Bridge, with a price tag of $88.7 million, is set to open later this summer. Meanwhile, the crumbling Sarah Mildred Long Bridge, which serves Route 1, is set to close in 2014.

Building jobs closer to home

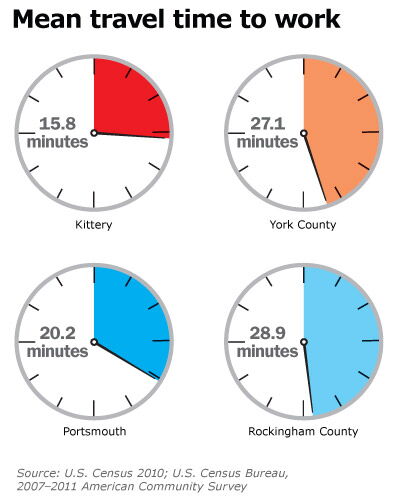

According to the recent census data, the average working resident of York County travels roughly 27 minutes to work. Regional planners would like to shorten that average commute by creating and filling more jobs closer to home. Some of their efforts have focused on calibrating the skill levels of the work force to meet the needs of local manufacturers, says Ouellette. Community colleges in southern Maine are offering targeted training that can lead to manufacturing jobs that pay one-and-a-half times the average salary in York County, he says.

"We're really looking at manufacturing as a growth sector for the southern part of the state," Ouellette says.

Jim Damicis, a developer with Camoin Associates and vice president of the Northeastern Economic Developers Association, believes York County is poised to take advantage of a boom in smaller-scale, decentralized manufacturing. The county has worked hard to upgrade its broadband fiber optic access through the recently completed Three Ring Binder project, which he believes will open the door to more on-demand, computer-aided manufacturing. Southern Maine also might be well-positioned to take advantage of a new small-scale manufacturing boom because of its proximity to major markets and its existing manufacturing infrastructure, he says. But the future of manufacturing will look different than manufacturing did in the past, he says. The days of attracting employers who hire 500 people at a time might be over, he says.

"Small is the new big," Damicis says. "Everybody thinks manufacturing is dead, but it's only dead if you look at the way manufacturing was."

If things break right in York County and manufacturing job openings climb, downtowns revitalize and public transportation options grow, it might provide enough enticements to attract out-of-staters to settle, says Schumacher. These positive trends, coupled with an outdoors ambiance and housing prices that are still low when compared to the rest of the region, might make southern Maine the newest hip place to live. The trick might just be in the marketing, he says.

"We're trying to sort of tie all of those things together into a brand for York County," Schumacher says.

Craig Idlebrook, a writer based in Massachusetts, can be reached at editorial@mainebiz.biz.

Mainebiz web partners

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments