Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- December 1, 2025

- Nov. 17, 2025

- November 03, 2025

- October 20, 2025

- October 6, 2025

- September 22, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

-

Our Events

Event Info

Award Honorees

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Critical access hospitals under federal scrutiny

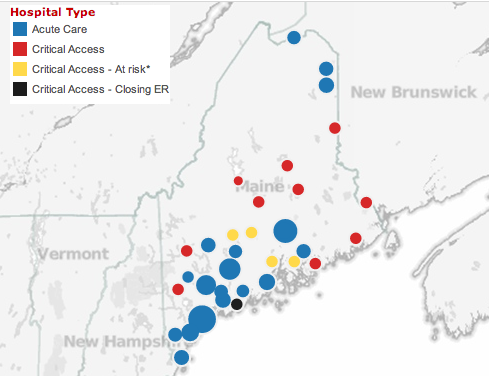

Browse the interactive map with this story for more information on hospitals in the state.

Browse the interactive map with this story for more information on hospitals in the state.

Maine hospitals will get some reprieve with the payment of $484 million in Medicaid debt on the way, but the state’s rural hospitals may face further challenges as designations allowing them to get higher reimbursements through Medicare are in jeopardy.

In 1997, federal lawmakers passed a payment initiative specifically designed for rural hospitals. The “critical access” program recognized that small hospitals in isolated areas might have essential functions despite low numbers of patients. Generally, that designation requires a hospital be more than 35 miles from another hospital or have access affected by bad terrain, and have 25 or fewer beds. Qualifying hospitals receive Medicare reimbursements at 101% of the allowable costs.

Joe Ditre, executive director of the advocacy group Consumers for Affordable Health Care, expressed skepticism about the critical access program being quite the lifeline it was predicted to be, but Maine Hospital Association President Steven Michaud said it remains vital to 16 of Maine’s smallest hospitals.

“It may not look like a lot of money,” he said of the generally higher reimbursement rates, “but it often makes the difference between showing a return or running a deficit.”

The federal Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General in August released a report calling for possible elimination of nearly two-thirds of the critical access designations nationwide, which it said do not meet the original definitions of “isolation” and are costing the federal government up to $1 billion a year more than the original law allowed.

Under the original law, governors were allowed to provide additional criteria for isolation, and many did. The DHHS report found 849 of the 1,329 critical access hospitals do not meet the 35-mile standard.

The projected savings of $449 million a year from the proposed reduction may not seem large given the hundreds of billions spent on health care annually, but Congress is under great pressure to find budget cuts wherever it can.

The Obama Administration has backed away from enforcing the full 35-mile standard, replacing it with a plan that would cut around $40 million in Medicare spending by removing from the program around 70 critical access facilities that are 10 or fewer miles from the next-nearest hospital.

Andrew Coburn, associate dean of the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine and a national expert on rural health care, said five hospitals in Maine would be affected if the original 35-mile rule were enforced: Waldo County General Hospital in Belfast, Blue Hill Memorial Hospital in Blue Hill, Redington-Fairview General Hospital in Skowhegan, Sebasticook Valley Hospital in Pittsfield, and St. Andrews Hospital in Boothbay.

While the fate of federal changes is unclear, pressure remains on critical access facilities around the state to stay afloat.

Last year, St. Andrews decided to voluntarily give up the designation as officials said emergency room usage had dropped so low that, in winter, there might be only a single case in a 24-hour period. Even the 11-visit daily average, they said, included many cases that didn’t actually require emergency care.

Michaud pointed out that the critical access designation isn’t a free lunch, however. Hospital stays, for instance, can’t be longer than 96 hours, often requiring transfer to larger hospitals at that point.

Michaud said he hasn’t heard of any other hospitals considering closing their ERs, but maternity wards could close at several hospitals.

“I know several are considering it,” he said. “It’s a less drastic step, because it doesn’t involve losing the acute care designation.”

Blue Hill Hospital closed its maternity and obstetrics unit as part of an apparently successful effort to close persistent budget deficits that threatened its future. Parkview Adventist Medical Center in Brunswick also eliminated maternity services after losing a regulatory battle to prevent Mid Coast Hospital, which had merged its Bath and Brunswick campuses, from delivering babies at its new Cook’s Corner location.

Though the shutdown at St. Andrews was delayed once, from April 1, it now appears it will happen next month, despite strong criticism in the community and lengthy news stories in the Portland Press Herald and the Boston Globe. St. Andrews, which partners with Miles Memorial Hospital in nearby Damariscotta, hopes to transfer its critical access designation under the federal Medicare program to Miles, and it will remain an urgent care center. But without an ER, it will no longer carry the hospital designation, leaving Maine with 38 acute care facilities.

Michaud said Boothbay shows how hard it is to actually shutter a hospital, or even reduce its care status.

“It’s seen as the heart and soul of the community, and a major employer,” he said. “It’s really part of a town’s identity.”

Coburn, at the Muskie School, agreed. “It’s like losing a town’s last school,” he said. “For many people, this is about a lot more than just health care. The philanthropy and the volunteer work that have gone into it are not easily given up.”

That local resistance to hospitals closures is paired with renewed pressure from Augusta to reevaluate the number of hospitals in the state.

Gov. Paul LePage recently told WCSH, in response to a report that Maine Medical Center was eliminating 225 positions, that “we definitely have too many hospitals,” adding that New Hampshire has 26 hospitals to serve the same number of people.

Ten years ago, a draft report for the Commission to Study Maine Hospitals, part of the Dirigo Health legislation, suggested that as many as 14 of the 39 state’s acute care hospitals could be considered redundant. A firestorm of criticism greeted the draft, and former Gov. John Baldacci disavowed it.

Michaud cautions that expecting huge savings from downsizing small hospitals is unrealistic. The six largest Maine hospitals, he points out, represent 50% of statewide revenue, while the 20 smallest comprise only about 15%.

“You could close all of them and still not get where you’re trying to go,” he said.

But for Coburn, it’s more about providing broad access and high quality at a reasonable cost — the three-legged stool that remains the prize for health care reformers. “Can we create the system that will actually satisfy these needs?” he said. “We’re not there yet.”

Read more

Mainebiz web partners

Related Content

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Comments