Fighting for equity: How Maine female entrepreneurs are beating the odds to raise capital

Photo / Tim Greenway

Briana Warner, CEO of Atlantic Sea Farms, is currently raising more than $4.5 million to fund a new 27,000-square-foot kelp-processing facility in Biddeford.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Briana Warner, CEO of Atlantic Sea Farms, is currently raising more than $4.5 million to fund a new 27,000-square-foot kelp-processing facility in Biddeford.

As Atlantic Sea Farms CEO Briana Warner raises more than $4.5 million in venture capital to finance a new 27,000-square-foot kelp-processing facility in Biddeford, she recalls early pitches to unwelcoming investors.

“It was fairly deflating in every way,” Warner says three years after taking the helm of the country’s first commercially viable seaweed farm, established in 2009. “It wasn’t unusual for me to walk into a room with a bunch of old white men and be told that ‘No one is going to eat kelp. What are you thinking, and why are you talking to us?’ and questioning my ability to understand basic facts about the world. I had one experience where someone said, ‘We know you present well, but can you sell kelp?’ with an insinuation about how I looked.”

The standard wasn’t the same for three fellow Ivy League alumni — all men — with a money-losing business and zero staff retention who received softball questions and got the $2 million they sought, according to Warner, who holds a master’s degree from Yale.

She, on the other hand, went in having raised $1 million and with a solid track record and business plan, “and they just threw daggers the whole time.” Though the investors later came round, Warner turned them away before due diligence after deciding she didn’t want to be in business with them.

“I’m happy for the guys to get that money, because if those investors are a--holes, at least I can vet them out before they’re in my cap table,” says Warner.

While the early setbacks didn’t stop Warner from winning over investors in Maine and elsewhere, her bumpy start typifies a male-dominated venture capital fundraising culture that’s long been inhospitable to women and is only slowly starting to change.

‘Smaller portion of a larger pie’

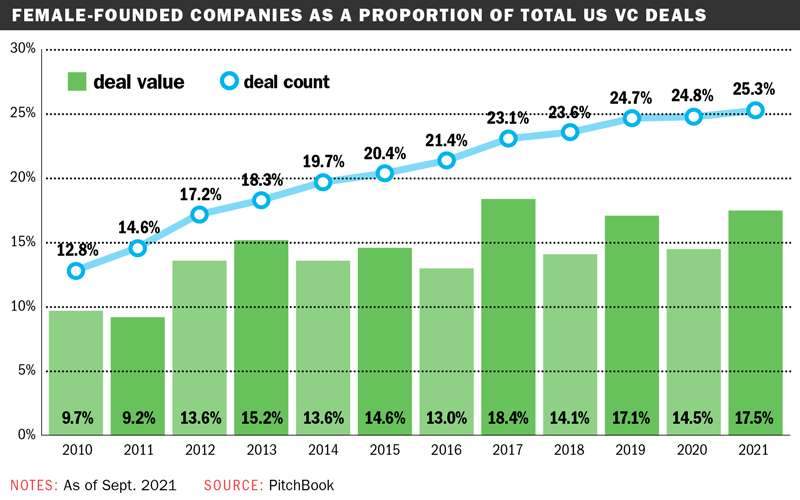

While mega-deals are propelling the U.S. venture capital industry to record highs, the proportion of money going to startups founded by women is declining.

In the first eight months of 2021, companies with all-female founders raised just 2.2% of venture funding, which according to Crunchbase is lower than any of the previous five calendar years. The picture is even grimmer for Black and Latina female founders, who received 0.43% of venture funding in 2020, down from 0.67% the year before, according to ProjectDiane figures cited by WIRED magazine in October.

Another report, released by PitchBook in early November, found that while the U.S. startup ecosystem increased deal value by 16% in 2020, VC dollars invested in female-founded companies fell by 3% and deal count fell by 2%, “meaning female founders received “a smaller portion of a larger pie.” Early-stage startups founded by women also saw median valuation increases of only 4%, trailing the 15% overall market increase.

Even as female founders are selling their companies more quickly and at higher valuations than the industry overall, they’re disadvantaged in the initial phases when courting potential investors — who are still predominantly male and pose different questions to different genders.

That’s well-documented in several places, including a 2017 Harvard Business Review study of interactions at an annual startup funding competition in New York. Researchers observed that while men were asked about potential gains (“How do you plan to monetize this?”) women were put on the defensive about potential losses (“How long will it take you to break even?”).

Perfecting business pitches

In Maine, Warner isn’t the only female startup leader — and successful fundraiser — to get curveballs from male investors and hit back with confidence.

Imagine, for example, explaining a breastfeeding support platform to a group of 50 men and only a handful of women, as Amy VanHaren had to do in Boston.

“I saw them all, I was nervous. I ended up going in and started my pitch saying, ‘Breastfeeding is really hard. Raise your hand if you feel me,’” the Kittery-based entrepreneur recalls of a pitch meeting for her company, called pumpspotting. “They looked at me for a minute and they all started laughing.”

Her response to them: “You’re going to have to take my word on this.” From those kinds of disconnects with investors, she learned the importance of reading a room and improved her storytelling skills with every pitch.

“The better equipped I was able to paint a clear picture, the more I was able to not only find the right investors quickly, but also some surprising champions,” says VanHaren, who raised $1.15 million last August in a seed round led by San Diego-based MooDoos Investments.

Another example is Torey Penrod-Cambra, co-founder and chief marketing officer of Portland-based industrial software maker HighByte, which raised $1.125 million in pre-seed funding in 2020 and won the $50,000 Gorham Savings Bank LaunchPad competition in June. Caught off guard in some pitches by questions she believes her male co-founders have never been asked, she now answers with a query of her own.

“When I’ve been asked questions about my personal life — specifically my ability to balance parenthood with entrepreneurship — it reminds me that gender inequity is still pervasive in our homes and professional lives,” she says.

“Rather than get upset, it’s more productive to respond with empathy and encourage the inquirer how they were able to balance those demands in their own life.” She also says that answering a question with a question is a good strategy in general, to tease out the “why” behind a question and get investors more engaged in the dialogue.

Among more seasoned entrepreneurs, Kay Aikin of Dynamic Grid — a Portland-based startup that designs intelligent energy for electrical grids — is having a tough time in her effort to raise funds for a solar project in Maine.

“It’s time-consuming, it’s frustrating, and I’m not good with rejection,” Aikin says after fruitless calls to investors as far afield as Ukraine, and a recent rejection — from a female investor in Canada — via a three-sentence email curtly thanking Dynamic Grid “for you-all’s time.”

Hoping to do better with a Boston community venture group she’s pitched to, Aikin says she’d like to see all venture capitalists look beyond what she calls “pattern matching” in vetting applications, and see more women on the financial side, noting: “We need more women investors, and we need more women tech investors.”

Meanwhile in Rockland, Shannon Kinney of digital marketing agency Dream Local Digital has some regrets about her own fundraising approach, saying, “My feminine tendencies wanted to make a deal work, and I made the deal work in a way that did not support enough future growth. My investors were so motivated about job creation in Maine, and I zeroed in on that part of the story,” she says. “I should have broadened my horizons regardless of how people felt.”

Now leading a company that has downsized by half during the pandemic, Kinney says she appreciates all her investors, particularly Sandra Stone, chair emerita of the Maine Angels group of early-stage private equity investors.

“As a female founder, you need smart money, not just any money,” Kinney says, “and Sandra for me was smart money.”

Heather Blease, owner and CEO of Brunswick-based call-center company SaviLinx, which raised $330,000 in 2015 from investors including Maine Angels and Bangor Angels, feels similarly though she’s also encountered hurdles in past pitches.

“One of my challenges,” she says, “was that my company did not have the intrigue of an interesting novel technology app, intellectual property or an invention with the potential of hitting it out of the park as an overnight success.”

More female checkwriters

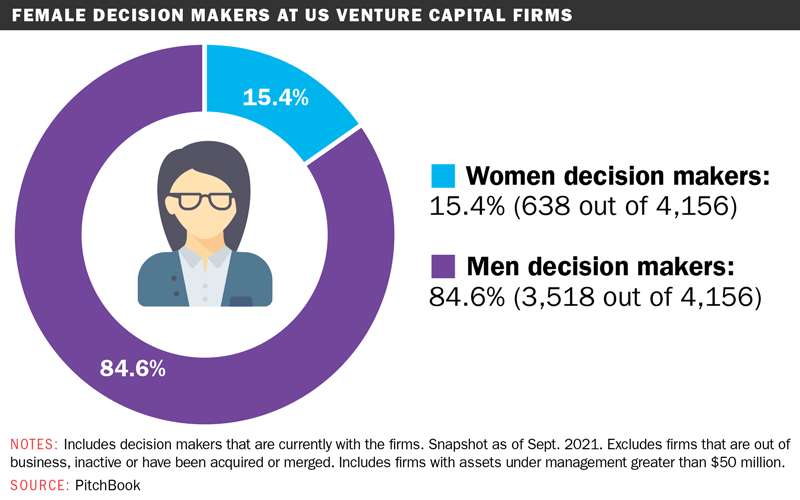

Nationwide, the number of female checkwriters at venture capital firms has increased by nearly 3.5% since 2019, with women now holding 15.4% of general partner positions, as documented by PitchBook. That’s significant because the presence of female investors in the room has been widely shown to boost chances of success for a female-founded company to secure funding.

More women are also entering angel investing, which PitchBook notes is an unheralded but important cog in the venture capital conveyor belt. Nationwide, the number of female angels has grown from fewer than 100 in 2010 to 895 today, as the pool keeps expanding.

That’s certainly true at Maine Angels, with about 30 female members out of 94 total and eight women-led startups in its portfolio including Atlantic Sea Farms, HighByte, pumpspotting and Dream Local Digital.

“Women like coming to Maine angels because we have women in the room,” says Stone. Along similar lines, Maine Angels member Susan Morris says it’s just as important to have enlightened men on board and attending gatherings focused on women: “Until the men equally show up, then we have not even cracked the surface because we’re preaching to the choir.”

While Maine Angels members make their own investment decisions, Robert Kelley of Port Clyde says he’s pleased that the group prioritizes diversity on a startup’s management team — which also guides him in deciding where to put his capital and expertise.

“I’ve turned my focus to exclusively funding and mentoring women and BIPOC entrepreneurs, helping them access capital, knowledge and management experience often historically denied them,” says Kelley, an investor in companies including Atlantic Sea Farms, Sara Rademaker’s American Unagi eel-rearing venture and Dream Local Digital, whose board he chairs.

Catherine York Powers, of Portland-based fintech startup Constant, recently recognized on the Forbes Next 1,000 list of entrepreneurial heroes, also has a mission-driven approach to her investments in small companies, but for personal reasons.

“Being a woman of color, I also look for opportunities to invest in folks like me, because it’s one thing to have hurdles as a woman, but those hurdles are even higher for women of color,” she says, thankful she didn’t encounter those hurdles in raising $7 million for her own startup.

Women helping women

Elsewhere in Maine’s startup ecosystem, Maine Venture Fund has a number of women-led firms in its portfolio with plans to add more, according to the fund’s new investment manager, Nina Scheepers, a former Unum product manager.

“When you look at returns, women-founded startups, or at least startups that have diverse representation, return more dollar per dollar of funding to their investors,” she says. “Analytically, you would want to be funding more women because those businesses are returning better capital.” Her tip to capital-seeking entrepreneurs: “Talk to us early.”

The same goes for Karin Gregory, co-founder and managing partner of Biddeford-based Blue Highway Capital, who urges female entrepreneurs to reach out to female investors. Gregory notes: “As Madeleine Albright once said, ‘There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help other women.’”

Mainebiz web partners

Congrats! Especially love Catherine York Power's comment: “Being a woman of color, I also look for opportunities to invest in folks like me, because it’s one thing to have hurdles as a woman, but those hurdles are even higher for women of color.”

1 Comments