Lending leverage | Credit unions push to raise a federal cap on small business loans

As commercial lending stalls at banks across the country, credit unions are increasing efforts to pick up the slack, aggressively pursuing a larger piece of that small business loan pie.

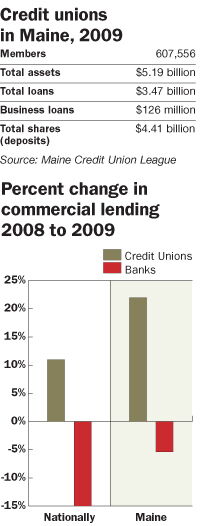

Nationally, commercial lending by banks has dropped 15%, according to the Wall Street Journal, while credit union commercial lending has increased by 11%. That increase is more pronounced in Maine, where credit union lending to small business is up 22%.

“Data indicate that Maine credit unions, both state and federally chartered, increased commercial loans $22.8 million in 2009 to $126 million, or 22% (over 2008),” says Lloyd LaFountain, superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Financial Institutions. “Maine banks decreased small business loans $145 million, or 5.4%, to $2.52 billion.”

LaFountain says the drop in bank lending to small businesses shouldn’t be misconstrued as a deliberate de-emphasis on small lending in favor of large business loans, but more a reaction to a stalled economy. Banks still underwrite the lion’s share of commercial loans in the state. But John Murphy, president of the Maine Credit Union League, says more than half of his 66 members have small business loans on their books — and many are seeking more.

“Credit unions have always been in the small business loan business,” he says. “Now, we’re looking to do more, to fill a gap.”

Murphy was in Washington, D.C., recently to lend his voice to lobbying efforts to expand credit unions’ ability to make commercial loans. Current law caps business lending at 12.5% of a credit union’s assets; bills before Congress now would lift that limit to 25%. Jay Chapin, CEO of Ocean Communities Federal Credit Union in Biddeford, says the average credit union has $125 million in assets. The maximum amount a credit union of that size could allocate to commercial loans is $15.6 million. Small business loans are defined as commercial loans with an original amount less than $1 million. In Maine, those loans are typically much smaller, falling in the range of $25,000 to $50,000, says Chapin.

Many credit unions — in Maine and elsewhere — predict they will soon reach that cap, which would restrict their ability to add more commercial lending to their portfolios.

Evergreen Credit Union in Portland is one. CEO Tucker Cole says Evergreen increased its commercial lending by about 30% last year over 2008, with 18% to 20% growth expected in 2010. The focus on business loans helps make up for other types of lending that have slowed. According to the Credit Union National Association, new auto loans dropped by 6.6% in 2008, and another 7.9% in 2009.

“Auto loans and other types of loans are pretty much drying up,” says Cole. “Small business is very important, but within the next 12 to 18 months, we’re probably going to bump up against that cap.”

At Evergreen, the bulk of the commercial lending is to small, micro businesses, the backbone of Maine’s economy, says Cole. “In this economy, small businesses are struggling,” he says. “I’m surprised at how badly some small businesses have been beaten up. And it’s not just the startups; a lot of long-term businesses are struggling as well.”

LaFountain doesn’t see the cap as a punitive measure, but as a control to ensure proper growth.

“The limitation is designed to force credit unions to enter the commercial loan business slowly and carefully,” he says. “As more credit unions gain experience and expertise in commercial lending, it is likely the limitation will be raised.”

Nor does he see it as a pressing issue at most credit unions.

“In most cases, in Maine at least, credit union commercial lending programs are relatively new,” he says. “Except for one federal credit union, the bureau does not believe there is any individual credit union with a commercial portfolio close to that 12.5% limitation.”

Still, the Maine Credit Union League is joining other state organizations and CUNA to push for the cap to be doubled. According to CUNA, that higher limit could create more than 100,000 new jobs and add more than $100 billion into the economy at no cost to taxpayers. Legislation to raise the cap is pending in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, but is widely opposed by small banks. This opposition is nothing new to credit unions. In fact, the cap was put in place in 1998 as a compromise between banks and credit unions in exchange for the expansion of credit unions’ membership eligibility requirements.

LaFountain says there are ways credit unions that may be facing that cap limitation can work around it.

“The NCUA (National Credit Union Administration) currently has the authority to grant a waiver of the 12.5% limitation for individual credit unions on a case-by-case basis,” he says.

But credit unions have found other creative work arounds. Chapin says Ocean Communities is part of Business Lending Solutions, a cooperative partnership of eight credit unions, which pool their resources to spread commercial loans among themselves to take advantage of eight caps, rather than one.

Another benefit of the co-op, Chapin says, is the financial wherewithal to hire two seasoned commercial loan officers. Based on their skill and experience — more than 55 years combined — one of their salaries alone would be cost-prohibitive for a single credit union.

The seven other members of the co-op are Maine Savings Credit Union, C-Port Credit Union, True Choice Credit Union, Atlantic Regional Credit Union, Five-County Credit Union and Cumberland County Credit Union.

Maine’s ‘bread and butter’

According to U.S. Department of Labor statistics, businesses with fewer than 100 employees accounted for about 45% of job growth from 1992 to 2008 — making the viability of small business a vital part of the national economy. With its population of only 1.2 million, Maine relies even more heavily on the success of those businesses to keep its economy afloat, Chapin says.

“Small business, along with tourism, is the bread and butter of Maine,” Chapin says.

Maine’s reliability on small business is a driving factor behind credit unions’ increased willingness to pick up where larger banks have left off on commercial lending, Chapin says.

“All the bank mergers have created a minimum threshold for commercial loans that is too high for a lot of small businesses,” he says. “In some cases, banks won’t look at anything under $250,000. That doesn’t help the guy who needs $25,000 to buy a new truck.”

Cole says credit unions are a natural fit for those smaller loans, which normally run anywhere from $25,000 to $5 million.

“The big banks’ blanket policies are pushing small businesses out the door,” he says. “That small business lending tends to be [credit unions’] forte.”

That’s not to say credit unions are essentially handing out small business loans, Cole adds. In Evergreen’s case, those loans fall under more scrutiny than ever before to ensure that borrowers will be able to repay the credit union.

“We try to be as personal as we can, take the time to get to know the borrower. How long have they been in business? Have they surviv ed a downturn before? Is this just a cash flow problem?” he says. “The answers to those questions, for example, play a big part in whether we’ll make the loan or not.”

Evergreen has also put some new policies in place to protect itself from those risks, including capping the maximum size loan any one borrower can receive and ensuring that potential borrowers have the means to collateralize the loan. Accurately valuing collateral is one of the biggest challenges Evergreen faces, Cole adds.

“An assessment may say collateral is worth one amount, but in the end, it’s really only worth market value — what it can be sold for today,” he says. “If the collateral isn’t there, we’ll also work to secure the loan with sub-debt through FAME (Finance Authority of Maine).”

Both CEOs agree on the ideal candidate — and the greatest risk — for small business loans.

“Obviously, the small businesses that have been around for a while and have a proven track record are more likely to get approval,” Chapin says. “The hardest loans to get are for startups; there’s no proven track record.”

Cole says Evergreen requires three years of success.

“The easiest deals to do are for businesses that have been around 25 to 30 years that may be having a short-term cash-flow problem,” he says. “We know they’ll pay back the loan.”

While it’s a necessary part of the lending process, it’s never easy to tell someone no, Cole says. That’s why Evergreen works with those who have been denied to identify alternatives. Ocean Communities also provides this counseling following a denial.

“We’re good at sitting down with them and doing an analysis of why they didn’t qualify to identify what they could do in the future to potentially make it work,” Chapin says.

Hopefully, there will be fewer denials as the economy begins its recovery. LaFountain says an uptick in commercial lending should happen across the board once the economy improves.

“Quality loan demand remains weak,” he says. “As both Maine banks and credit unions are in relatively good condition, are strongly capitalized and have ample liquidity, the bureau expects commercial loan growth will resume once economic conditions are more favorable.”

Derek Rice, a writer based in Saco, can be reached at editorial@mainebiz.biz.

Comments