Processing Your Payment

Please do not leave this page until complete. This can take a few moments.

- News

-

Editions

-

- Lists

-

Viewpoints

-

Our Events

-

Award Honorees

- 2025 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2025 Outstanding Women in Business

- 2024 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2024 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2024 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2023 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2023 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2023 Business Leaders of the Year

- 2022 NextUp: 40 Under 40 Honorees

- 2022 Women to Watch Honorees

- 2022 Business Leaders of the Year

-

-

Calendar

-

Biz Marketplace

- News

-

Editions

View Digital Editions

Biweekly Issues

- September 22, 2025

- September 8, 2025

- August 25, 2025

- August 11, 2025

- July 28, 2025

- July 14, 2025

- + More

Special Editions

- Lists

- Viewpoints

- Our Events

- Calendar

- Biz Marketplace

Plan now or pay later: Succession plans are taking on a greater importance at businesses

Photo / Tim Greenway

Denis Landry, president of Landry/French Construction, left, and Kevin French, executive vice president, at the construction site for the new Scarborough public works building. They set up an Employee Stock Ownership Plan to ensure the firm’s longterm viability.

Photo / Tim Greenway

Denis Landry, president of Landry/French Construction, left, and Kevin French, executive vice president, at the construction site for the new Scarborough public works building. They set up an Employee Stock Ownership Plan to ensure the firm’s longterm viability.

Kevin French, 55, has no immediate plans to retire, not even a decade from now.

“If I’m having as much fun in 10 years as I’m having now, I don’t see myself retiring,” says French, executive vice president of Landry/French Construction in Scarborough.

A few years ago, during his quarterly strategy meeting with the firm’s president, Denis Landry, the two broached the topic of succession planning for the first time.

“We really wanted to get ahead of the curve and think about it,” French says. After studying various options, they decided to transfer ownership to employees through a tax-friendly trust known as an Employee Stock Ownership Plan.

“It’s allowed us to grow our business, and not worry about how we’re going to get out from underneath someday,” French says. “It also helps us retain and attract new employees since everybody gets a piece of the pie.”

With a workforce of around 60, the firm had revenues of $68 million in 2018, up from $65 million in 2017. French says that while it’s still too early to name a possible successor from current employees, “we’re providing the tools and seeing how they grow.”

Unlike French and his partner, surprisingly few business owners plan for retirement — even in this state with its aging population and abundance of small businesses. That can be self-defeating for those counting on a retirement income from the eventual sale of their business.

“Generally for small businesses, it’s a challenge,” says financial consultant Pete Ventre of Carrot Seed LLC in Portland. “They’re making a salary they’re living off comfortably, and when they stop working, that salary stops. Even if they sell their business to someone else, the return they get will be far less than their salary.”

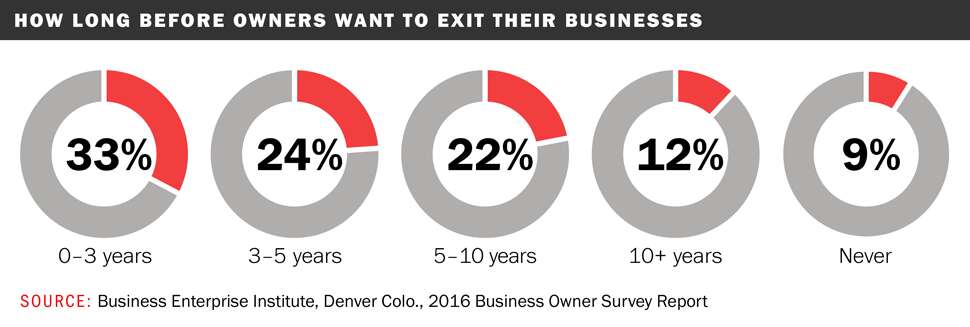

As more baby boomers enter their golden years, a 2016 report by the Denver-based Business Enterprise Institute looked at the problems business owners face as they retire. It found that only 17% of owners have a written business-exit plan, even though most want to leave within the next decade and three out of four would do so today if their financial security were assured.

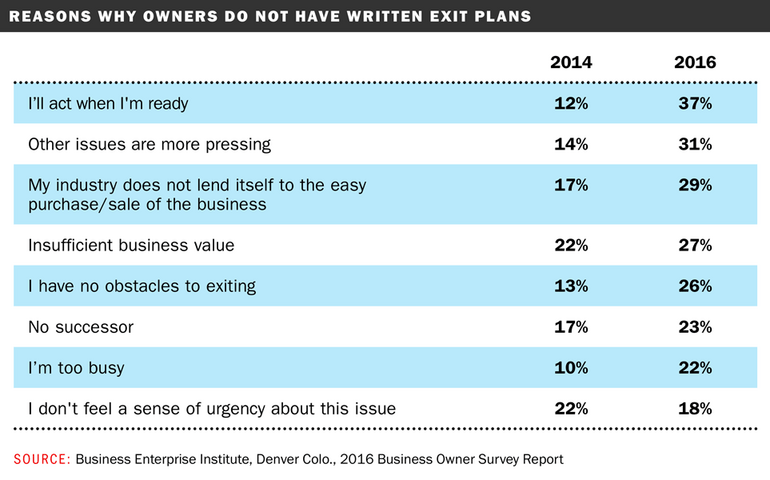

Reasons given for the lack of planning ranged from “I’ll act when ready” to “I don’t feel a sense of urgency about this issue” to “I have no obstacles to exiting.”

In fact, the number of owners who believed they could leave their business at any time doubled between 2014 and 2016, to 26%. More troubling is that owners rarely seek advice from an outside expert, preferring to keep it in the family.

Getting caught off guard

Maine has lots of real-life examples of business owners getting caught off guard. They include Ron Blake, the 68-year-old owner of Cote Bros. Sewing Machines in Turner. Four years ago, he hired someone he was grooming as a successor for the retail division and with whom he had a gentleman’s agreement to sell the business so that he could retire. A day after that deal was supposed to go through, the intended buyer backed out, blaming an inability to get financing.

“This is the second time I’ve been burnt and I should have known better,” admits Blake, who’s giving up the retail operations after a three-day inventory fire sale and a last-minute Facebook plea for anyone interested in buying the business by May 9. “This is a case where nice guys finish last.”

Blake, who still went ahead with a two-week Florida vacation with his wife, Lisa Cote-Blake, says he will “semi-retire” upon his return, working three or four days a week from home selling industrial sewing machines and parts.

Reflecting on the failed deal, Blake says it may have had a better chance had he owned rather than leased his retail shop and had a firm exit plan in place. “I thought I had one but I didn’t have it locked up,” he says.

That may be sound advice for Marcia Feller, owner and founder of the Couleur Collection women’s clothing and art gallery on U.S. Route 1 in Falmouth. About to turn 72, she says she’s too busy to plan retirement.

“I think about it all the time and I’m doing absolutely nothing about it right now,” she says. “When I think about slowing down and not having a big component of this business, I panic.”

But she does take comfort in extending her lease on the 3,600-square-foot space every five years.

“My business is not for sale, but if at some point I find a younger woman who wants to take it on, this is a valuable lease,” she says.

Succession success stories

Maine succession success stories include Sheridan Construction in Fairfield, which has gone through three ownership transitions since it was founded as a family construction firm in 1947. The last was in 2017, when Mitchell Sammons and Daniel Wildes bought the company from Brad Nelson, who retired.

Sammons, who owns 51%, serves as president, while Wildes is senior vice president and chief operating officer. The two talk about succession planning once a month as Sammons hopes to retire in a couple of years.

“We continue to look at succession and we’ll probably follow the pattern we have in the past,” says Sammons. “I’m now 66, and my plan is to work out some sort of transition to him [Wildes] and his next management team.”

They work closely with David Jean, managing partner of Altus Exit Strategies LLC in Portland, a subsidiary of Albin, Randall & Bennett CPAs. Jean is a CPA and one of 200 exit planners in the United States — and the only one north of Boston, he says — certified by Colorado’s Business Enterprise Institute.

Focusing mainly on mid-sized firms with an enterprise value between $3 million and $10 million, Jean describes his work as “holistic exit planning” rather than just transactions. That work usually begins with a readiness assessment of 22 questions to business owners.

It always surprises me how unprepared business owners are for transition.

—David Jean, Altus Exit Strategies

“It always surprises me how unprepared business owners are for transition,” says Jean. “I’m not the therapist, but we look at their financial and emotional readiness to think about succession planning. Emotional barriers are often more of a challenge than financial ones.”

Family-business tensions

Those who advise family-owned businesses say that emotions also run high in decisions about passing the baton to the next generation.

“Emotions are difficult to separate in a family business,” says Brien Walton, director of Husson University’s Center for Family Business in Bangor, “so the CEO may overlook the lack of commitment or competence of their favorite child because they want that particular child to represent the family. More second-generation business owners have failed for this reason more than any other.”

Walton’s recommendation: “The selection process should be no different from hiring any top executive in a non-family business.”

Peter Plumb of Portland law firm Murray Plumb & Murray also suggests greater communication among family members to avoid unrealistic assumptions.

“Business owners who hope and pray that the business will somehow stay in the family are the ones that really need to start having family meetings early on,” he says, recommending an exit plan from the get-go: “The day you walk into the office as the chief executive is the day you want to start planning your exit.”

And Catherine Wygant Fossett, executive director of the Portland-based Institute for Family-Owned Business, recommends designating someone in the family as a planning “champion” who holds everyone accountable. To help its members manage business transitions, the institute’s Next Generation Peer Advisory Group’s “Leaders in Transition” holds regular information sessions, including one planned for June 20 at Husson’s Westbrook campus.

A range of scenarios

While there are several ways for owners to exit their business and retire, Bill Haskell of Bellview Associates in Ellsworth boils it down to three options: Sell to a competitor, financial investor or to employees through an ESOP. He sees the last as the best option for firms whose owners plan to be around for the next few years, as with Landry/French, which he advised on its ESOP.

“It’s also a good recruiting tool for new employees because everyone that comes in is going to be a part owner,” he says.

French says that’s definitely the case, along with ensuring the Landry/French name lives on: “We want to see our names on the sign and new buildings being built when we’re 90.”

Mainebiz web partners

Related Content

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

Learn More

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

Learn More

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

Learn more-

The Giving Guide

The Giving Guide helps nonprofits have the opportunity to showcase and differentiate their organizations so that businesses better understand how they can contribute to a nonprofit’s mission and work.

-

Work for ME

Work for ME is a workforce development tool to help Maine’s employers target Maine’s emerging workforce. Work for ME highlights each industry, its impact on Maine’s economy, the jobs available to entry-level workers, the training and education needed to get a career started.

-

Groundbreaking Maine

Whether you’re a developer, financer, architect, or industry enthusiast, Groundbreaking Maine is crafted to be your go-to source for valuable insights in Maine’s real estate and construction community.

ABOUT

NEW ENGLAND BUSINESS MEDIA SITES

No articles left

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

Get access now

In order to use this feature, we need some information from you. You can also login or register for a free account.

By clicking submit you are agreeing to our cookie usage and Privacy Policy

Already have an account? Login

Already have an account? Login

Want to create an account? Register

0 Comments