The Maine Department of Marine Resources is in the midst of a first round of meetings with the lobster industry, to discuss strategies to cope with an expected 50% cut in the number of “endlines” in the water.

Endlines are the vertical lines that connect lobster traps that are on the ocean bottom with a buoy at the sea surface. The buoy identifies where the traps are, and the vertical lines are used to haul up the traps.

The agency is holding the meetings with Maine’s seven Lobster Management Zone Councils during June to facilitate the development of a proposal that meets targets established by the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team for protecting right whales, according to an agency news release.

The team has recommended broad measures for Maine that include removing 50% of vertical lines from the Gulf of Maine and the use of weak rope in the top of remaining vertical lines. The measures put forward by the team are driven by federal laws designed to protect whales. The laws are the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Complicated scenarios

DMR Commissioner Patrick Keliher plans to work with each zone to develop a proposal that meets the team’s goals.

The agency held its first meeting on June 4 with Zone B, which encompasses fishermen in the region from Schoodic Peninsula to Surry, including Mount Desert Island.

Keliher and agency staffers presented a variety of scenarios to achieve the reductions. The scenarios included potentially reducing the number of traps allowed to each fisherman, as well as connecting more traps to each other, called “trawling up,” on the bottom, which would reduce the number of endlines. For example, an inshore area might currently allow a fishermen to haul “pairs,” or two connected traps, from the bottom with a single endline. That could potentially be modified to triples, meaning a fisherman would haul three traps with a single endline.

Approximately 30 scenarios, so far, are based on various configurations of reduced trap numbers and increased trawling-up.

For example, fishermen today are allowed a maximum of 800 traps. In that scenario, within state waters, if everyone fished four traps per endline, there would be a 53% reduction of risk.

It’s expected that weak sections of rope would help a whale break out of an entanglement. However, the weak section must remain strong enough for a lobsterman to haul the rope.

“The whole thing is complicated but, at the end of the day, we have to have a conversation about all these pieces,” said Keliher.

“Not all the scenarios made it to 50%,” said Carl Wilson, director of the agency’s bureau of marine science. “The tool box is pretty empty on how we can get there.”

Risky areas

The agency is also looking at what areas of Maine and what time of year the risk is greatest, said Wilson. For example, he said, right whales have been spotted north of Mount Desert Rock.

“That’s considered a risky area by some, so that was given a different weight,” he said.

Other measures under consideration include vessel tracking in federal waters, 100% reporting by harvesters regarding their fishing activity, and gear marking. Those measures are designed to better identify where entangling gear originated and where lobster gear and right whales intersect. Maine currently has a 10% harvester reporting requirement.

Maine’s DMR is calling for a quarter-mile exemption zone from any measures in inshore shallow waters, Keliher said. That would help maintain fleet diversity by allowing smaller boats and children who have a student license to continue to fish as they have been, he said.

Given the expected restrictions on the fishery, the industry will likely also look into new licensing reductions, Keliher said. However, he added, the agency will continue to support diversity in the fishery. Diversity includes types of boats, from inshore skiffs to big offshore boats; the ability of fishing family offspring and apprentices to enter the fishery; and different fishing practices through the region.

Part of the problem is that the distribution and habitat use of right whales in the Gulf of Maine is shifting, said Erin Summers, with the agency’s protected resources division.

“There are a lot of unknowns in the question of where are they at any given time,” Summers said.

Audience members pointed out that any of the new measures will likely cause changes in fishing practices, which will then have to go under review again.

For example, one said, fishermen who typically frequent federal waters, who are required to trawl up a higher number of traps, might decide to move into state waters instead to take advantage of the lower trawl-up numbers, thus increasing the number of vertical lines overall.

Federal regulators, responded Keliher, “realize that whatever we do, everything will change. And they’ll look at it again.”

The agency will process input from the zones after the first round of meetings and return for a second round in August, Keliher said. DMR is scheduled to submit its proposal to the National Marine Fisheries Service, which is the federal regulating agency on the matter, in September, he said.

The schedule calls for the service to publish its proposed rule and seek public comment on the proposal sometime this coming winter. Implementation of new regulations could occur in 2021, Keliher explained.

The Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Team convened in April to develop additional measures to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale.

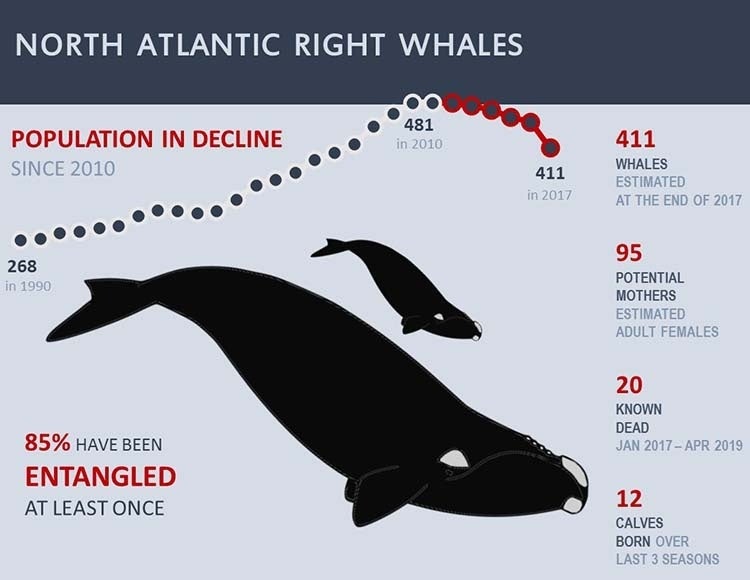

The federally convened team consists of approximately 60 fishermen, scientists, conservationists, and state and federal officials. The group advises the National Marine Fisheries Service, which is the federal body that would enact any regulations. Although there was steady population growth from about 270 right whales in 1990 to about 480 in 2010, a downward trajectory began after that.

The downward trend was exacerbated by an unprecedented 17 deaths, particularly within the Gulf of St. Lawrence snow crab fishery, in 2017.