Reform readout | A guide for diagnosing the impact of federal health care law in Maine and six preventative measures you can take now

If you’ve been following the path of the federal health care reform that just cleared Congress, you’ll be relieved to know that any neck strain caused by the incessant volleying between the House and Senate, the Democrats and Republicans, qualifies as a pre-existing condition. Hence under the terms of the new law, you can’t be denied coverage.

It’s just one of the ground-breaking, industry-shaking changes enacted under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, signed by President Obama on March 23 and tweaked slightly by Congress. Promised to reduce the numbers of uninsured Americans by 32 million and the federal deficit by $124 billion in 10 years, the act forbids health insurers from denying coverage and charging higher premiums based on health status and gender, and imposing lifetime limits on coverage, among other rules.

Will it cure what ails us? We’re not sure, but now that the politicking is done (or at least it’s taking a breather) we thought we’d roll up our sleeves and see if we can make sense of the practical impact the new law will have on businesses here in Maine.

The basics

Beginning in 2014, most people will be required to have health insurance. For people who don’t have access to an affordable plan through their employer, they can get coverage through new health insurance exchanges that will be set up in each state. Credits will be available to help with the premium costs for people who meet income guidelines and for small businesses.

By 2014, states must set up competitive exchanges, which allow companies with fewer than 100 employees to pool their resources to buy health insurance. Until the exchanges are established, businesses with 10 or fewer full-time workers earning less than an average of $25,000 will be eligible for a 35% tax credit. Companies with up to 25 workers with an average salary of less than $50,000 will receive partial credits, while businesses with 25 or more workers will receive no credits.

After 2014, small businesses with no more than 25 employees that purchase coverage through an exchange can get a 50% tax credit of the employer’s contribution toward an employee’s health insurance premium for two years, after which the credit phases out.

Employers will also have to help out their employees who meet income guidelines and want to purchase insurance on their own if the company’s premiums are too expensive. If an employee is making $11,000 a year and the company’s premiums cost more than $880 a year (more than 8% of their income, but less than 9.8%), the employee has the option of purchasing his own insurance through one of the exchanges. The employer has to provide that employee with a free choice voucher, equal to what the firm would have kicked in to provide coverage through its own plan.

If a business has more than 50 employees and does not offer health insurance, the consequences of the new act are pretty dire. If that company has at least one employee receiving a premium credit through an exchange, it must pay a $2,000 fee per employee after the first 30. So for a company that doesn’t offer coverage with 65 employees, at least one of whom receives the premium credit to purchase insurance through an exchange, the company would have to pay $70,000 in fees.

Employers that provide free choice vouchers, however, won’t be subject to penalties for employees that get premium credits in the exchange.

Employers that do offer coverage and have at least one employee receiving a premium credit are required to pay the lesser of $3,000 for each employee who receives a premium credit, or $2,000 for each full-time employee.

Businesses with fewer than 50 employees — the vast majority of those in Maine — are exempt from the penalty fees.

For Maine’s employers with more than 200 employees who offer coverage, they will have to automatically enroll employees into their lowest-cost premium plan if the employee doesn’t sign up for it, or does not opt out.

So, here are some questions and answers to help you make sense of the act.

How many businesses in Maine could be subject to the penalty for firms with more than 50 workers that don’t provide coverage?

Rep. Chellie Pingree’s office, citing the Kaiser Family Foundation, reports that of the 1,778 businesses in Maine that employ more than 50 people, almost 97% currently offer health insurance.

The state Department of Labor most recently surveyed Maine businesses about insurance coverage in 2006. According to that study of 2,400 businesses, 93% of firms with 50 to 99 employees contributed to their workers’ health care premiums. For companies with 100 to 249 employees, the percentage rose to 98.5%, and almost all businesses with 250 or more workers contributed to coverage.

So, that leaves only a handful of businesses that would be subject to the penalty. But companies that offer coverage and have at least one full-time employee who receives a premium tax credit may have to pony up. Those employers could have to pay the lesser of $3,000 for each worker receiving the credit or $2,000 for all full-time employees. But businesses that offer a voucher to employees who opt to enroll in an exchange plan, instead of the company-provided plan, won’t be subject to that penalty. The vouchers would be available to workers whose incomes are less than 400% of the federal poverty level — about $88,200 in Maine for a family of four — and whose share of the premium tops 8% but amounts to less than 9.8% of their income. The voucher would make up the difference between what the employer would have owed to cover the employee under its own plan.

Will it make financial sense for some businesses with more than 50 workers to drop health coverage in favor of paying the fines?

It might. “It’s really an economic or financial calculus,” says Andrew Coburn, chair of Health Policy and Management at the Muskie School of Public Service at the University of Southern Maine. Some employers on the fiscal ropes who can’t afford to provide coverage may take the penalty hit but not actually pay the fine, he says. The question remains whether the subsidies and penalties provide enough incentive, he says. But employers have other reasons, such as a desire to attract quality candidates, for offering health coverage. “Generally speaking, all things being equal, the preference is to offer health insurance to employees,” he says.

Will we see businesses with about 50 employees either avoid hiring or lay off workers to stay below the threshold and avoid the penalty?

The reforms undoubtedly put pressure on businesses to tighten up headcounts, according to James Ward, president of Patient Advocates in Gray, which helps employers design benefit plans. “You’re going to see employers look back to see where they can cut back,” such as through outsourcing or automation, he says. But Coburn says employers will consider the money they spent hiring and training workers before laying them off just to avoid a penalty fee. “This isn’t a decision someone’s going to make lightly to avoid a $3,000 or $4,000 expense,” he says.

Why is 50 employees the cutoff point?

According to Sen. Olympia Snowe’s office, 50 workers is a fairly standard threshold for small business exemption in federal law, such as the Family and Medical Leave Act. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, also defines the small group insurance market as employers with two to 50 workers.

What will happen to Dirigo Health?

“We’re well positioned because Dirigo is essentially an exchange,” says Trish Riley, director of the Governor’s Office of Health Policy and Finance. The program already operates a health care tax credit through a program for workers displaced by foreign trade and administers vouchers to part-time, seasonal and direct-care workers at large companies. The Maine Quality Forum, an independent division of Dirigo that promotes healthy practices and collects and publishes health care data, would “clearly continue,” perhaps without much change, Riley says.

With the reform law’s federal subsidies, Dirigo could become more attractive, and Maine could also enter into a multi-state exchange, as Sen. Olympia Snowe has advocated, Coburn says. But Ward says Dirigo appears to have been rendered redundant. “Why wouldn’t Dirigo just pack up its tent and say, ‘OK, we gave it a nice try’?”

Staff reports

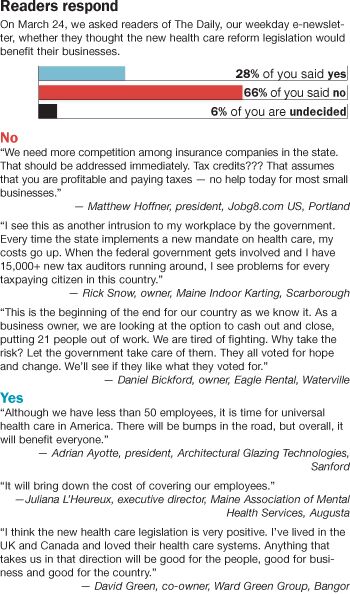

Comments