UMaine panel: Self-driving vehicles could build on ‘live and work in Maine' trend

Screenshot / University of Maine

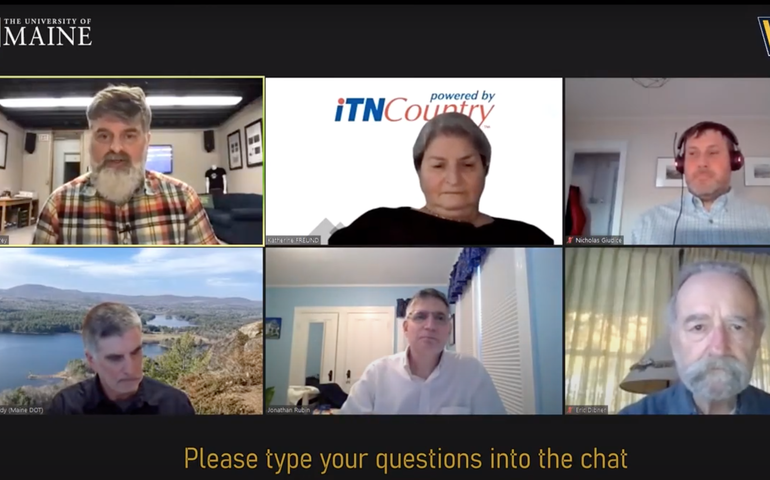

Clockwise from top left, VEMI Lab co-founder Richard Corey; Katherine Freund, founder and president of the Maine-based Independent Transportation Network of America; VEMI Lab co-founder Nicholas Giudice; Maine Department of Transportation Transportation Research Engineer Dale Peabody; Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center Director Jonathan Rubin; Maine State Accessibility Coordinator Eric Dibner.

Screenshot / University of Maine

Clockwise from top left, VEMI Lab co-founder Richard Corey; Katherine Freund, founder and president of the Maine-based Independent Transportation Network of America; VEMI Lab co-founder Nicholas Giudice; Maine Department of Transportation Transportation Research Engineer Dale Peabody; Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center Director Jonathan Rubin; Maine State Accessibility Coordinator Eric Dibner.

The pandemic has led to huge changes in the way people live and work. The emergence of self-driving vehicles technology could also mean a similar shift in the way they travel by car or bus, experts at a University of Maine forum said last week.

The emergence of self-driving vehicles could get a boost from lessons learned during the pandemic, according to a panel discussion held by UMaine's Virtual Environments and Multimodal Interaction Laboratory, or VEMI Lab.

Digital technology has already allowed people to choose new homes and types of work during the pandemic, said Jonathan Rubin, director of Maine’s Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center. To the extent that autonomous vehicles save time — a major cost to getting around — it’s reasonable to think they'll have the same impact on those choices.

“I think this has profound implications for settlement and work patterns in Maine,” he said.

The discussion was one of a series of events that were part of UMaine’s Maine Impact Week, an annual showcase of the research, creativity and public service from the University of Maine community.

Rural accessibility

As part of a collaboration between UMaine, Northeastern University and Colby College, VEMI Lab is exploring applications of emerging transportation technology as it relates to accessibility needs. In 2020, the lab received $300,000 as a semifinalist for the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Inclusive Design Challenge, which seeks solutions to make automated vehicles accessible for all.

Autonomous vehicles have great potential to improve the quality and availability of public transportation, particularly for Maine’s dispersed population in rural areas, where it can be difficult for people who don’t drive to go anywhere, said VEMI Lab co-founder Nicholas Giudice.

The technology has a great deal of promise for older people, agreed Katherine Freund, founder and president of the Maine-based Independent Transportation Network of America. With people being able to work, read or sleep while being transported, autonomous vehicles could spur people to move from urban to rural areas, she said.

But fear will likely inhibit adoption among older people, she continued. Still, older people take up “passive” technology more quickly than “active” technology.

For example, people who might not want to learn how to program a VCR will agree to an MRI because they don’t have to know how to use it. Autonomous vehicles might follow a similar path: People will just have to climb in and go. Freund also predicted that people will like that they don’t have to depend on someone else to travel.

There’s also some thought that autonomous public transportation could benefit tourism.

“You’d think that people would welcome the idea of flying in or taking a train, maybe going to Bangor, and then having the ability to get on an autonomous bus to travel to Acadia,” said Maine Department of Transportation Research Engineer Dale Peabody.

Trust gap

Most people will say they like the concept of autonomous vehicles but don’t trust it, said Giudice.

“There’s a huge trust gap that needs to be solved,” he said. “This is true of most new technologies.”

In 2019, the lab received a $500,000 National Science Foundation research grant to tackle that issue. The project centers on “human-vehicle collaboration,” an idea designed to address perceived loss of control over driving activities. The goal is to improve user trust of autonomous vehicles and explore how information is communicated between the human passenger and the artificial intelligence “driver.”

Key to boosting acceptance of autonomous vehicles, said Giudice, will be finding out “how to make these two intelligences feel more comfortable together.”

Also in discussion is the type of infrastructure changes that would be needed. For example, he explained, traffic signals and vehicles would have to be able to connect with each other. The questions come down to basic items such as whether road lines and signs would have to be better maintained so vehicles can read them.

“We don’t want to invest lot in the infrastructure without knowing what exactly the need is,” Peabody said.

Then there’s the question of how many gasoline stations will still be needed, if autonomous vehicles become the primary transportation mode, to satisfy residual demand for internal combustion engines.

“I don’t think we’ll lose internal combustion engines,” said Rubin.

Linked technologies

The state of Maine has begun working with the other New England states to look into collaborative legislation and policies that would enable the implementation of autonomous vehicles, said Peabody.

But the question of most interest was when, exactly, autonomous vehicles will become commonly available.

Giudice predicted they would be present at some level in five years, with more robust adoption within a dozen years.

According to one report, said Peabody, the technology is linked to electric vehicle infrastructure, which is gaining momentum for what could be an “explosion” of EV sales in the coming decade.

Panelists noted the technology is also linked to digital connectivity in order to allow the vehicles to communicate with non-vehicle digital infrastructure.

“Broadband availability will have something to do with where these vehicles can go safely,” said Maine State Accessibility Coordinator Eric Dibner.

The question of when the technology will become commonly available depends on proprietary information, noted VEMI Lab co-founder Richard Corey.

“There are so many multiple factors that could adjust when this could happen or how it could happen,” he said.

Giudice added, “Some people say within two years, others within 40, 50 years."

But, Freund said, "everyone agrees it will happen at some point."

0 Comments